Mgr. Igor Tyšš, PhD.

Department of Translation Studies,

Constantine the Philosopher University in Nitra, Slovakia

ityss@ukf.sk

Abstract

The article deals with the history of Slovak audiovisual translation (AVT) research. The author uses a bibliography of Slovak AVT resources, which he has been compiling since 2013, and combines the data with other relevant sources (microhistories, close reading of relevant articles, data from political and cultural history, etc.) to create a complex historiography that would retain the complexity of its object. In order to question the traditional paradigm of scientific research as progress, the author employs Foucault’s discourse analysis to critique the claim that having more publications means a better field and rounds up his discussion by suggesting that Slovak AVT theory is suffering from genesis amnesia (Bourdieu), since it is by and large ignoring its past.

Introduction

The statement that audiovisual translation (AVT) has seen growth in impact and academic visibility in recent years has almost become a truism. Such are the facts on the ground: the ever-growing connectedness of the world, the relative accessibility of film and information technologies (and the resulting chance of viewing habits) have contributed to the rise of visibility of audiovisual translation. Of course, this visibility has lead ever more powerful market agents to get hold of it, too. The aim of this study is to describe and analyze Slovak thinking on audiovisual translation in its historical development from the standpoint of current trends in Slovak AVT. The underlying rationale for such an objective is that every field of human activity that generates theoretical discourse is worthy of historiography, if only in relation to the notions of progress and social change (cf. Pym 2010) or change itself (Haris, Harari 2018). This study is based on ongoing bibliographical research (later on referred to as “the Bibliography”), parts of which have already been published (Tyšš, Janecová 2014; Tyšš 2015) and which is still a work in progress. Unlike other histories of AVT (e. g. O’Sullivan 2011 or Raffi 2016), this is not an overview of the development of audiovisual translation practice, but an overview of local AVT(-related) theory and research initiatives in a specific context with the view of the overall state of AVT.

Of course, it can be argued that “theory” does not full reflect the scope, impact, and cultural and historical relevance of translating and translation. Arguments for or against the usefulness of theory have been with translation studies ever since its prehistory, and it can be argued (as, in fact, Levý 1971 has) that theory is useful and valid insofar it helps to better understand the factors influencing the work carried out in the profession. The history of the field in Slovakia shows that in audiovisual translation there has very often been friction between the frameworks proposed by theorists and the experience of the practitioners. Of course, the rapid development of technology only adds a potent dose of indeterminacy to the mix. In this perspective, it is not surprising that some scholars claim that due to its vital and vivid connection to technology – and therefore its rapid development – AVT has become “the engine for eclectic thinking within the field of TS” (Díaz Cintas, Neves 2015, 2), and they argue for a bottom-up approach to what is being done in the field (Baňos Piñero, Díaz Cintas, 2015). Such voices and calls for more interdisciplinarity demonstrate the great self-awareness of the discipline.

An entirely different point, however, is the disciplinary status of AVT in Slovakia. Based on the bibliographical data and on the personal experience from being present at the turning points in the development of AVT theory in Slovakia, I do not consider AVT to be an autonomous discipline in its own right (yet). Rather, it is more feasible and useful to view AVT as part (or a subdiscipline) of translation studies. Wherever it is referred to as “discipline” in the following text, this is because of the Foucauldian connotations of the term.

The way we construe the scope of audiovisual translation, what lies within and outside its boundaries, determines our way of cataloging the subdiscipline’s publications. However, critical readings of bibliographies always shed light on their illusory completeness and leave open the possibilities for their expansion or restriction (if need be). Thus, from the erudite bibliographer’s perspective a bibliography can never be complete, and a translation historian would say that it never should be viewed as such. Bibliographies help us reveal the fragmentariness and discontinuities (Bednárová 2013) which are a natural part of translation history and which can only be explained incrementally, on a case-by-case basis. Seen from this perspective, it seems relevant and fruitful to use bibliographical research as a source of a deeper translation cultural history and use a descriptive methodology to discover the context, the discursive tensions, and power struggles present in the formation of a field of translation practice.

In such a historical survey of AVT the notion of discipline seems a useful concept. In this discussion we shall draw on Foucault (1981) who sees discipline as a sociological construct based on the phenomenon of setting up and protecting one’s own discursive space. Every discipline is defined by its own discourse (its language, most prominently, though not exclusively, represented by its terminology – cf. look at the roles encyclopedias or terminological dictionaries played in the establishment of translation studies) and a set of prerequisites one has to fulfill to become accepted as established in the field. These prerequisites, however, are more often than not social constructs, and a historical survey is bound to show their steady adoption and all the social hum-drum (a Marxist would call it ‘struggle’) going along with it. For the sake of clarity, however, in this discussion we are going to adopt the traditional props of historiography – timelines, discussions of notable personalities (not limited to the great men in history), boundaries, and metaphors. At times, however, we are going to problematize them and may even venture to tear down some metaphorical walls.

Bibliography: structure, what got in (and what did not)

At present, the Bibliography lists publications from the period between 1952 and 2017 (including), and it is the most comprehensive catalog of Slovak AVT publications. It covers the discipline from what we can say (so far) are its beginnings in the 1950s up to its present-day bibliographic records. However, the research conducted so far suggests that the beginnings of thinking about AVT (“research” or “scholarship” imply a degree of systematicity and organization that had not materialized in the early periods) go even further into the past, perhaps to the 1940s, if not earlier. At the same time, it is immensely difficult – if, at times, not outright impossible – to research and properly catalog the earlier periods of Slovak AVT research history due to the lack of dedicated publication spaces, inaccessibility of the texts themselves, and also incomplete, and, thus, not entirely reliable, paratextual metadata. Many of the first relevant theoretical publications on film were published solely as internal materials of production companies, and we only have paratextual information about them. More often than not, however, the metadata on these older publications is inaccessible or incomplete. Without first-hand archival research of the available documents, whose fruitfulness is highly questionable (due to the sparsity of direct treatment of translation), it is at present impossible to pinpoint the exact year when Slovak AVT research started. Given the significance of the first article on AVT mentioned in the Bibliography (Branko 1952), one could argue that we have found a decent enough start.

At present the Bibliography contains 183 entries. The entries have been chosen on the basis of three working definitions.

- Def. 1: The Bibliography comprises every text that deals with all aspects of audiovisual translation from the standpoint of the translation process and product, i. e. taking into account the communicatively bilateral or multilateral, praxeological, and stylistics specifics thereof.1

- Def. 2: The Bibliography comprises every text which has been published and/or reasonably peer-reviewed (given the circumstances).

- Def. 3: The Bibliography comprises every thematically relevant Slovak text that has been referenced or discussed by Slovak AVT scholar or professional both in writing and at relevant conferences or workshops about AVT.

As for the scope of AVT in terms of its research interests, the definition the bibliography adopts has been deliberately made as broad as possible. This takes into account the current state of research activities in Slovakia (e. g. a systematic treatment of SDH or the beginnings of research of SDH and audio commentary in theater, or even the research of sign language in AVT) but also the dynamic development of the field itself in recent years, and the need for further sociological surveys. Yet, it has been even more difficult to determine what falls into the scope of AVT in Slovakia when it comes to applied research transcending the borders of individual disciplines, such as audiovisual translation in theater, the use of audiovisual translation in foreign language teaching or the often problematic intersections between AVT and linguistics.2

The corpus includes published texts (i. e. texts with an ISBN code and publisher’s details) on all aspects of AVT that are pertinent to its current state. As of the present, the bibliography excludes students’ BA or MA theses (so long that they have not been published so far) but, on the other hand, includes doctoral theses (due to them having undergone a peer-review process and gradual progress assessment).

It has proved immensely difficult to determine what falls into the scope of audiovisual translation in the older period of the discipline’s development from the 1950s and 1960s. If we are to follow the working definitions stated above, we still encounter a number of problems when reading older texts, since they very rarely address the issue of translation in AVT directly and primarily (like Branko 1952). More often than not the texts from the 1950s and 1960s are about films as such and only partially address some translational aspects (like e. g. the need to dub films for children, (er) 1957; or the definition of dubbing in an article about the spelling of this word, cf. Dvonč 1968). Still, the notes remain very sparse and unsystematic until the 1970s.

A brief history of Slovak AVT research: events, personalities, publications

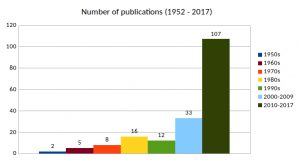

The following chart illustrates the number of Slovak publications dealing with AVT on a decade-by-decade basis.

From the way things stand in raw numbers, it might seem that the development of AVT research in Slovakia has followed a trajectory of growth. However, there are two caveats that should be brought forward when describing the rapid growth in Slovak AVT research since 2010. The first caveat is the so-called principle of reversal. This is a methodological consideration which has been defined and applied by Foucault (1981). He argues that even though the proliferation of a particular discourse might seem a positive phenomenon, from a methodological point of view we must see it as something negative, since the “rarefaction” of discourse bars us from recognizing its true nature and significance. In other words, it is better to be wary of any particular discourse growth; therefore, it is advisable to look at it from different perspectives. Secondly, even the number of publications is somehow misleading when zeroing in on the volume of publications from the most recent times. In fact, the moment we look more closely at the numbers in the period after 2010, our view becomes more nuanced.

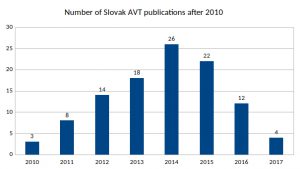

After a closer look at the number of publications after 2010 it becomes clear that after 2014 the number of publications in the field saw a year-by-year decline, with the most drastic one in the last year. This trajectory seems to be more natural: after a period of unnatural proliferation this shows that the field has become established and that the numbers are not the only indicator of relevance. Just as a matter of fact, when we look at the significantly cut-back year 2017, we could still argue that it was an important year since it saw the publication of two vital texts, both of whom somewhat synthesize two important strands of research from the previous years.

The monograph of Lucia Paulínyová (nee Kozáková) Z papiera na obraz: proces tvorby audiovizuálneho prekladu [From the paper to the screen: The process of audiovisual translation] is the first comprehensive account of the dubbing process in Slovakia. The book is the result of years of research that combine both the author’s practical experience as a dubbing translator and editor and her thought-out survey of the relevant theory and methodology (with an emphasis on the Czechoslovak tradition). The second important text of the year was penned by the most prominent and renowned Slovak AVT scholar, Emília Perez, whose name is featured with over 40 entries in the Bibliography. Among other AVT-related research activities, Perez has researched the Slovak standards of SDH ever since 2013 and her 2017 chapter titled “The Power of Preconceptions: Exploring the Expressive Value of Subtitles for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing” (part of the Languaging Diversity monograph series) helped this research gain momentum by being published for an international audience. Even though it is still not feasible to list a definitive set of causes of the decline in the number of AVT publications since 2015, two points ought to brought up:

- Such decline is a natural feature of natural discourse behavior: after periods of proliferation, characterized by over-production and a chaotic plurality of topics and voices, come “calmer” periods when the discourse has established itself on a number of topics and is propagated by a limited number of lead exponents. This is what happened to Slovak thinking on AVT after 2014: the discipline had established itself, and the number of researchers who continued to work within the field narrowed down to the ones who seem to pursue AVT as their main research interest.

- As shown above, the decline in the number of publications seems to bring along a noticeable growth in impact in degree of synthesis. The data we have at hand, however, does not establish a correlation so far.

Since this is still a history-in-the-making, this is the farthest the data we have at hand allows us to go. Seeing how valuable the two publications from 2017 are, it could be argued that bibliographic data should by all means be supplemented by other data and relevant interpretations to get to a full historical account.

A very tentative timeline

The following passages are an attempt at a historical explanation (Pym 2010) whose aim is to explain the historical development of AVT research in Slovakia. We are going to use the data provided by the Bibliography and contextualize it by looking at the contents of the most important publications, the development of Slovak translation studies, and other relevant historical events pertinent to the discussed timeline. The timeline follows the individual decades of the later half of the 20th century and the early part of the 21st century, since this is the most straightforward way to approach such a history in the making.

The early period of Slovak audiovisual translation research (1950s – 1970s)

Slovak interest in AVT grew from very humble beginnings (in fact, the Bibliography features only two entries). Notwithstanding the sparse remarks on foreign films in Slovak cinemas and the occasional remarks that they were in fact subtitled, most of the texts from the 1950s remain irrelevant. Most noteworthy texts that did indeed focus on film, and some authors published remarks on film theory and history, appeared in the magazine Film a divadlo [Film and theater] which started its run in 1957. However, even the texts in this dedicated (not “specialized”, since this was a popular publication) magazine sidestepped the translational aspect of foreign films. The most relevant article on AVT comes from the year 1952 and it was written by prominent film critic and translator Pavol Branko, who to this day remains one of Slovakia’s most significant film theorists. The title of the article is self-explanatory: “K problematike filmových podtitulkov” [On subtitles in films].

For the sake of our discussion, it is important to note that Branko takes great pains to emphasize the synthetic, Gestalt-like qualities of film:

Yet, it is imperative that subtitles be done from the film, not only from the dialog list. Every work of art, film included, is a complete unity. Film is an art form of synthesis and – unlike other forms of art – it is a sum of several artistic constituent parts. Let us look at an example: Literature has at its disposal only one expressive means, which is language, and it has to use it to express everything. Film also uses language, but it is only one of its constituent expressive parts. Film has other modes of artistic expression – theater, painting, illustration, and music. Thus, it could be said that film synthesizes four art forms, and it achieves its fullest potential when the forms connect and work together; when there is complete unity between them. [In film] these constituent parts create a new, specific art form by means of their unity, an art form different from each and any of its parts […] which means that the parts can no longer be viewed as autonomous works of art (1952: 215, transl. I. T.).

By viewing film as a synthetic medium with its own language, Branko’s approach stands at the beginning of a paradigm of thinking about film in Slovak AVT which I propose to call the film semiotics methodology. This approach takes into consideration the specific qualities of film as an independent art form, characterized mostly by its unique set of artistic conventions and style, i. e. its own film language.

Branko’s article is also ripe with concrete examples in which he discusses the interdependence of the language and dialog features of the film with its other features. This article is also a sharp critique of contemporary working conditions and even work ethics in a centralized film industry.

The following decade also brought a small number of articles relevant to today’s AVT (five in total). Audiovisual translation is treated only as a side note in articles about film festivals (Branko 1967) or film music (Bernstein 1969).

While in the 1950s Branko (1952) implied that subtitles were the most dominant and useful mode of AVT (since the most widely adopted audiovisual media, films, could practically only be watched in cinemas), the situation had changed dramatically by early 1970s. The continuing development of technology, the growth of consumer culture, and also the steady reduction of working hours brought TV culture to Czechoslovakia. This is notable when we sift through the pages of the most widely known magazine which also covered audiovisual culture. The already mentioned periodical Film a divadlo started out as a black-and-white publication dedicated mostly to high culture such as cinema and culturally relevant films; it featured rather technically sounding reviews and at times even ventured into drama or film theory. Starting in the second half of the 1960s the periodical changed into a color format and started covering more and more of popular audiovisual culture; it contained interviews with movie and TV stars and brought news from cinemas around the world.

Two important articles on AVT theory were published in this decade. These two texts mark a watershed moment in the development of Slovak AVT research, since this is the first time the term “theory” can be used to describe Slovak texts about AVT without any reservations. These two texts demonstrate that the then-developing Slovak translation theory, whose founder and main powerhouse of ideas Anton Popovič (1933 – 1984) had planned for an integrated translation theory that would cover all aspects of translation, had started moving over to – and indeed integrating – audiovisual translation. Both texts were written by the same person, Katarína Bednárová, who was a student of Anton Popovič and very apt theorist in her own right. The first text, titled “K problematike filmovej a televíznej adaptácie literárneho diela” [On film and TV adaptations of literary texts], she uses a semiotic-communicative approach and sees adaptation for the screen as a case of intersemiotic translation; the second text, “Dabing ako spôsob jazykovej komunikácie” [Dubbing as a means of language communication] can be viewed as a confirmation of the facts on the ground – dubbing had by then become the most dominant form of audiovisual translation in Slovakia. All in all, it could be argued that by the end of the 1970s Slovak translation started showing interest in audiovisual communication and developing a linguistic semiotic research methodology for studying AVT. The linguistic semiotic approach would in time become so dominant that it would push out the older film semiotic methodology.

Enter: Translation studies (1980s)

During this era a number of articles on dubbing (e. g. Kenda 1982, Považaj 1983, Hlaváčová 1985) were published whose overall aim is to educate the public about the specifics of this AVT mode. Apart from that, translation theorists and researchers treat AVT on a regular basis. Some synthetic works on translation (Ferenčík 1982; Popovič et al. 1983) feature contributions on aspects of AVT which are synthetizing in nature (e. g. Bednárová 1983a, 1983b) or synthetizing articles appear in other publications (like Hochel 1985 on the communicative aspects of TV translation). A very important article is Bednárová’s take on documentary film commentary translation (1983b), the first article dealing with this topic from a TS perspective in Slovakia.

In this context, however, we must mention an article not referenced enough these days. It is by Vojtech Benedikovič, and its title is “Funkcia titulku ako tlmočníka filmového dialógu” [Functions of subtitles as intermediaries of film dialogs]. This paper, published in a specialized journal on film and theater, is understood as part of film theory. The author’s novel approach to the topic has been highly commended in the article’s peer reviews. This article stands on the intersection of film theory and translation, albeit not translation studies. It is quite notable, that the author discusses the complex functions of subtitles in their relation to film scenes and film dialogue, but not in their relation to the informational content or the utterance. Even though the author does also refer to linguistic works (e. g. Mistrík), he uses information theory (Wiener) and he does not use linguistic semiotics. On the whole, it could be said that Benedikovič’s article is a synthesis of the film semiotic approach to AVT where one could clearly see that AVT can be viewed as an essential and natural part and parcel of the unique film audiovisual experience.

What is also notable is that in 1986 Csonka, Mistrík, and Ubár penned their Frekvenčný slovník posunkovej reči [Frequency dictionary of sign language], a very relevant and unique publication, whose appearance demonstrates that sign language research has had a track record in Slovakia – and publications like this one would be of great use in AVT research in the following decades.

The Roaring 1990s in Slovak audiovisual translation

Even though the 1990s were a period of dynamic changes and development of the AVT industry in Slovakia (brought by the decentralization after the fall of communism in 1989 and the rapid changes of film technologies), the list of relevant topics covered by Slovak AVT has remained largely unchanged. When looking at the Bibliography, one finds a number of short, almost irrelevant articles on the state of dubbing in the new post-1989 social conditions (e. g. Muríň 1990, Borovičková 1995, Grečner 1996) as well as on the state of Slovak cinema (Hradiská 1995), and the impact of new technologies on the AVT practice is discussed as well (mainly the DVD phenomenon – Redeky 1999a, 1999b). The only translation studies synthetic publication that to a degree covers AVT is Hochel’s 1990 Preklad ako komunikácia [Translation as communication] where the author has included a very general and brief chapter on dubbing.

2000-2009: AVT finding its place on the map of Slovak translation studies

We can view the beginning of the 20th century as an era when translation studies finally gained its ground in Slovakia. This is the time when many translation study programs were established or reinvigorated at Slovak universities, many new academics came to the fore, and the profession faced new realities with Slovakia’s accession to the European Union. However, the dynamic nature of the times did not lead to many notable translation studies contribution to AVT research. Instead, this period can be more appropriately understood as an interstitial – an advertisement of sorts for what was to come.

An interesting tendency that would later become a vital part of AVT study in Slovakia is the engagement of AVT practitioners in the academic discourse, demonstrated by a famous pivotal article on dubbing by Lesňák (2003), which is an overview of the dubbing practice from the translator’s point of view, and Makarian’s (2005) monograph on sound design in the dubbing process, for a long time the only of its kind in Slovakia. An important researcher who deals with sign language is Darina Tarcsiová whose works have further helped open up sign language to translation studies researchers.

A surprisingly pertinent issue for Slovak AVT that came up in the early 2000s was how to call the new subdiscipline, since this would impact (and have repercussions for) the terms and conditions that would define it in relation to translation studies. Prominent translation scholar Edita Gromová, who reestablished translation studies in Nitra, proposed the name “translation for the audiovisual media” (2008). The rationale behind this term was that it would a) emphasize the translational and intersemiotic nature of the said activities and, thus, align their research with the objective of translation studies (a logical move, given the times); b) drawing on the second part of the name, the scope of “audiovisual media” would allow translation studies to further expand. Later on, however, this term was dropped in favor of a more straightforward name – audiovisual translation, a term that would be more in line with the naming conventions outside Slovakia but whose originator also convincingly argued for roots in the Slovak tradition (cf. Kozáková 2013).

2010 – 2017: New challenges vs. old limitations

The number of relevant topics covered by Slovak AVT scholars has expanded, as has the number of publications, after 2010 when the discipline saw not only attempts to establish and explain itself by means of further marking out its space in translation studies (Gromová, Janecová 2012; Kozáková 2013), but the growing interest brought topics such as AVT teaching (Gromová, Janecová 2012; Janecová 2012; Janecová, Želonka 2012). Moreover, first steps toward sociology were made as early as 2014 (Janecová 2014; Želonka 2014). However, I would argue that sociological approaches have still not been adopted to their full potential, since studies focus mostly on the diversions between norms of national standards and their practical realizations (Perez et al 2016); what is still absent is statistical studies of concrete social phenomena pertaining to audiovisual translation that would help “bust the myths” about this profession (cf. Djovčoš, Šveda 2017).

The discussion of topics after 2010 would be incomplete without considering topics that were introduced to Slovak AVT research from other areas of academic or social interest. While it could be argued that such traditional topics as dubbing, subtitling, voice-over and the rest mentioned above very much form the internal discursive space of the discipline, since they have been conceptualized by translation studies methodology, there are other relevant topics featured in Slovak AVT which have been brought over from the outside and have only gradually been explored using relevant TS methodology. These topics from the “outside” include sign language interpreting in the audiovisual media, subtitles for the deaf and hard-of-hearing, and audio commentary. They first came to the fore in 2013; however, publications of (possible) interest to AVT date back to the 1980s. Therefore, it could be argued that the mentioned year marks the beginning of an adoption process. The division between “insider” and “outsider” topics is based on the bibliographical data: the “insider” publications appeared as part of the mainstream of the discipline (they were published by recognized scholars and even partially presented at prominent Slovak conferences and workshops). On the contrary, “outsider” publications – even though content-wise they are as relevant as the former – have appeared in publications which are not often referenced by translation studies scholars and they have been authored by experts who are not considered to be members of the translation studies field (even though some of them are members of the audiovisual translation profession).

The watershed year in Slovak AVT research history is the year 2012. The number of publications reached double digits for the first time in the history of Slovak audiovisual translation studies. The 1st real Slovak workshop (or rather, unofficial conference) dedicated solely to audiovisual translation in Slovakia was The Audiovisual Translation Studio 1, organized by E. Perez in Nitra, which brought together practitioners (notable dubbing producers, directors, and translators) and academics.

This year also brought the first collaborations on AVT theory between E. Gromová, who in the first decade of the 21st century managed to put together the threads of theory based on the approaches of the Nitra school, and up-start young academic and practitioner Emília Perez (nee Janecová) whose approach combined an ever deeper knowledge of international AVT theory with practical experience in the field and sociological surveys.

This year also saw the publications of scholars who would become the dominant voices in the field and would help establish the dominant – and indeed, at the time most pertinent – research themes.

These were in fact the days when the new subdiscipline sought to establish and explain itself by means of marking out its space in translation studies. Slovak AVT theory and research started displaying both eccentric and concentric tendencies in its treatment of impulses from other areas of human knowledge relevant to the research field.

What follow are the tendencies instigated in 2012 that impacted future research:

- attempts to integrate and properly evaluate the experience of practitioners and come up with an integrating (not neutralizing) conceptual frameworks and methodologies (as seen mostly in the works of E. Perez and L. Paulínyová)

- attempts to explore the experience of formerly marginalized groups of AVT practitioners and audiences: this marked the beginning of SDH and audio commentary research spearheaded by Emília Perez

- attempts to compare the state of Slovak theory with AVT theory from outside Slovakia on a broad enough basis that would lead to new impulses and new approaches be introduced to Slovak research

- research of AVT in Slovakia after 2012 also started focusing on social aspects, since it could be argued that the year brought the modern sociological turn to Slovak translation studies (with the publication of Djovčoš’s 2012 pivotal sociological survey of the Slovak translation market)

Bearing all this in mind, it is not hard to see that 2012 was indeed a watershed year in Slovak AVT research.

Conclusions

This survey of Slovak audiovisual translation research history is still, like the Bibliography, a work in progress. However, like every good bibliography, every good history requires expanding, rewriting, and correcting. So, the question is: What has Slovak AVT research been like?

Bearing in mind the limitations of my own view of things and the pitfalls of over-interpretation as well as over-simplification, I would call Slovak audiovisual translation research a field which suffers from genesis amnesia. The term comes from the classic of critical sociology Pierre Bourdieu who defines genesis amnesia as follows:

Thus the genesis amnesia which finds expression in the naive illusion that things have always been as they are’, as well as in the substantialist uses made of the notion of the cultural unconscious, can lead to the eternizing and thereby the ‘naturalizing’ of signifying relations which are the product of history (2000, 9).

Suffering from genesis amnesia means that you have only a vague notion that your field has had a history and that things were not always the way they are now. A dynamic field of inquiry suffering from this nasty type of amnesia would ignore the complexity of its object of study. This is what I think happened to Slovak AVT studies: from the 1990s onward the field has largely forgotten about film semiotics, and even the most prominent scholars have tended to treat audiovisual phenomena as mere functions of linguistic semiotics.

Another classic – nobody knows which one, perhaps that is amnesia, too – claimed that those who do not learn from their past are destined to repeat it. We have seen that there is something really unnatural and unconvincing about perpetual progress; however, it is not really useful to repeat the same fallacies.

References

(er). 1957. Dubbovať filmy pre deti?. In Film a divadlo, vol. 1, no. 12, p. 19.

Baňos Piñero, Rocío – Diaz Cintas, Jorge. 2015. Audiovisual Translation in a Global Context. In Audiovisual Translation in a Global Context: Mapping an Ever-changing Landscape. Eds. Rocío Baňos Piňero and Jorge Díaz Cintas. Basingstoke – New York: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 1 – 10.

Bednárová, Katarína. 1983a. Preklad textu filmových dialógov. In Originál/Preklad : Interpretačná terminológia. Bratislava : Tatran, p. 242-245.

Bednárová, Katarína. 1977. K problematike filmovej a televíznej adaptácie literárneho diela. In Slavica Slovaca, vol. 12, no. 4, p. 383-387.

Bednárová, Katarína. 1979. Dabing ako spôsob jazykovej komunikácie. In Panoráma, vol. 5, no. 2, p. 30-36.

Bednárová, Katarína. 1983b. Preklad textu komentára k dokumentárnemu filmu. In Originál/Preklad : Interpretačná terminológia. Bratislava : Tatran, p. 245-247.

Bednárová, Katarína. Dejiny umeleckého prekladu na Slovensku I: Od sakrálneho k profánnemu. Bratislava : VEDA, 2013.

Benedikovič, Vojtech. 1987. Funkcia titulku ako tlmočníka filmového dialógu. In Slovenské divadlo, vol. 35, no. 3, p. 291-326.

Bernstein, Leonard. 1969. HUDBA a FILM. In Hudobný život, vol. 1, no. 4, p. [8]-[8].

Borovičková, Alena. 1995. Sporná pasáž o dabingu českých filmov. In Pravda, vol. 5, no. 249 (27. 10. 1995), p. 16.

Bourdieu, Pierre – Passeron, Jean-Claude. 2000. Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. Transl. Richard Nice. London, Thousand Oaks, New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Branko, Pavol. 1952. K problematike filmových podtitulkov. In Slovenská reč, vol. 17, no. 7-8 (7.1952), p. 214-233.

Branko, Pavol. 1967. Logika absurdity čiže o nemožnosti filmových festivalov. In Film a divadlo, vol. 11, no. 23, p. 14-15.

Csonka, Štefan – Mistrík, Jozef – Ubár, Ladislav. 1986. Frekvenčný slovník posunkovej reči. Bratislava : Slovenské pedagogické nakladateľstvo.

Diaz Cintas, Jorge – Neves, Josélia. 2015. Taking Stock of Audiovisual Translation. In Audiovisual Translation: Taking Stock. Eds. Jorge Díaz Cintas and Josélia Neves. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, p. 1-7.

Djovčoš, Martin – Šveda, Pavol. 2017. Mýty a fakty o preklade a tlmočení na Slovensku. Bratislava : VEDA.

Djovčoš, Martin. 2012. Kto, čo, ako a za akých podmienok prekladá : prekladateľ v kontexte doby. Banská Bystrica : Univerzita Mateja Bela, Fakulta humanitných vied.

Dvonč, Ladislav. 1968. Dubbing – dabing. In Slovenská reč, vol. 33, no. 2, p. 125-126.

Ferenčík, Ján. 1982. Kontexty prekladu. Bratislava : Slovenský spisovateľ.

Foucault, Michel. 1981. The Order of Discourse. Translated by Ian McLeod. In Untying the Text: A Post-Structuralist Reader. Edited and Introduced by Robert Young. Boston – London – Henley : Routledge – Kegan Paul.

Grečner, Eduard. 1995. Dabing – umenie či trest?. In Filmová revue, no. 1, p. 8.

Gromová, Edita – Janecová, Emília. 2012. Preklad audiovizuálnych textov na Slovensku – prekladateľské kompetencie a odborná príprava. In Preklad a kultúra 4. Nitra; Bratislava : Filozofická fakulta Univerzity Konštantína Filozofa v Nitre; Ústav svetovej literatúry Slovenskej akadémie vied, p. 135-143.

Gromová, Edita. 2008. Preklad pre audiovizuálne médiá. In Slovo – obraz – zvuk : Duchovný rozmer súčasnej kultúry. Nitra : Filozofická fakulta Univerzity Konštantína Filozofa v Nitre, p. 136-143.

Harris, Sam – Harari, Yuval Noah. 2018. #138 – Te Edge of Humanity. In Waking Up Podcast [online], September 19, 2018. Available at: https://samharris.org/podcasts/138-edge-humanity/ [cit. 04-11-2018]

Hlaváčová, Agáta. 1985. O televíznom dabingu. In Nové slovo, vol. 27, no. 12.

Hochel, Braňo. 1985. Communicative Aspects of Translation for TV. In Slavica Slovaca, vol. 20, no. 4, p. 325-328.

Hochel, Braňo. 1990. Preklad ako komunikácia. Bratislava : Slovenský spisovateľ, 1990. Chapter Preklad v dabingu, p. 78-83.

Hradiská, Nina. 1995. Zánik kina na Slovensku?. In Nové slovo bez rešpektu, vol. 5, no. 48, p. 19.

Jakobson, Roman. 1959. On Linguistic Aspects of Translation. In Fang, Achilles et al. On Translation. Cambridge, Massachussets: Harvard University Press, p. 232-239.

Janecová, Emília. – Želonka, Ján. 2012. Didaktika prekladu pre audiovizuálne médiá : výzvy, možnosti, perspektívy. In Preklad a tlmočenie 10 : Nové výzvy, prístupy, priority a perspektívy. Banská Bystrica : Fakulta humanitných vied Univerzity Mateja Bela v Banskej Bystrici, p. 359-369.

Janecová, Emília. 2012. Preklad pre audiovizuálne médiá na Slovensku : výzva (nielen) pre akademické prostredie. In Letná škola prekladu 11 : Kritický stav prekladu na Slovensku?. Bratislava : Slovenská spoločnosť prekladateľov umeleckej literatúry, p. 99-108.

Janecová, Emília. 2014. Audiovizuálny preklad : teória vs. prax. In Audiovizuálny preklad : Výzvy a perspektívy. Nitra : Univerzita Konštantína Filozofa v Nitre, p. 51-60.

Kenda, Milan. 1982. Dubbing : Irolex. In Smena na nedeľu, vol. 17, no. 23, p. 10.

Kozáková, Lucia. 2013. Koncepcia audiovizuálneho prekladu. In Letná škola prekladu 12 : Odkaz Antona Popoviča, zakladateľa slovenskej prekladovej školy – pri príležitosti 80. výročia jeho narodenia. Bratislava : Slovenská spoločnosť prekladateľov umeleckej literatúry, p. 149-158.

Lesňák, Rudolf. 2003. Špecifiky dabingového prekladu. In Letná škola prekladu : Prednášky z XXIV. Letnej školy prekladu v Budmericiach 18. 9. – 21. 9. 2002. Bratislava : Stimul, p. 128-131.

Levý, Jiří. 1971. Bude literarni věda exaktní vědou?: Výbor studií JIŘÍ LEVÝ. Praha: Československý spisovatel.

Makarian, Gregor. 2005. Dabing : Teória, realizácia, zvukové majstrovstvo. Bratislava : Ústav hudobnej vedy Slovenskej akadémie vied.

Muríň, Peter. 1990. K právnej problematike dabingu. In Osvetová práca, vol. 40, no. 19, p. 13-15.

O’Sullivan, Carol. 2011. Translating Popular Film. Basingstoke : Palgrave Macmillan. 243 p. ISBN 978-0-230-5791-8.

Paulínyová, Lucia. 2017. Z papiera na obraz: proces tvorby audiovizuálneho prekladu. Bratislava: Univerzita Komenského.

Perez, Emília et al. 2016. Audiovizuálny preklad a nepočujúci divák : problematika titulkovania pre nepočujúcich. Nitra : Univerzita Konštantína Filozofa, Filozofická fakulta, 2016. ISBN 978-80-558-1119-2.

Perez, Emília. – Tyšš, Igor. 2014. Bibliografia slovenských prác o audiovizuálnom preklade do roku 2013. In Audiovizuálny preklad : Výzvy a perspektívy. Nitra : Univerzita Konštantína Filozofa v Nitre, p. 177-180.

Perez, Emília. 2017. The Power of Preconceptions: Exploring the Expressive Value of Subtitles for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing. In Languaging Diversity Volume 3 : Language(s) and Power. Newcastle upon Tyne : Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2017. ISBN 978-1-5275-0381-6, p. 188-204.

Popovič, Anton et al. 1983. Originál – Preklad : Interpretačná terminológia. Koncepcia a redakcia Anton Popovič. Bratislava : Tatran.

Popovič, Anton. 1975. Dictionary for the Analysis of Literary Translation. Edmonton : Department of Comparative Literature, The University of Alberta.

Považaj, Matej. 1983. Niektoré problémy slovenského dabingu. In Kultúra slova. 1983, vol. 17. no. 6, p. 203-207.

Pym, Anthony. 2010. Method in Translation History. Manchester : St. Jerome Publishing.

Raffi, Francesca. 2016. Subtitling and Dubbing the Italian Cinema in the UK During the Post-war Period.In Perez, Emília – Kažimír, Martin (eds.). Audiovisual Translation : Dubbing and Subtitling in the Central European Context. Nitra : Univerzita Konštanina Filozofa v Nitre. ISBN: 978-80-558-1088-1, p. 63 – 74.

Redeky, Juraj. 1999a. In DVD, DVD a opäť DVD… In PC revue, vol. 7, no. 12, p. 97-98.

Redeky, Juraj. 1999b. Pravdivý príbeh o filmoch na DVD. In PC revue, vol. 7, no. 7, p. 73-74.

Tyšš, Igor. 2015 Bibliografia slovenských prác o audiovizuálnom preklade do roku 2015. In Audiovizuálny preklad 2 : za hranicami prekladu. Editors: Lucia Paulínyová, Emília Perez. Nitra: UKF, p. 131-149.

Želonka, Ján. 2014. Kultúrno-spoločenské aspekty prekladu audiovizuálnych textov v slovenskom audiovizuálnom priestore. Dizertačná práca. Nitra : Filozofická fakulta, Univerzita Konštantína Filozofa v Nitre.

The research conducted for this article was supported by VEGA, under grant No. 2/0200/15 Preklad ako súčasť dejín kultúrneho priestoru II. Fakty, javy a osobnosti prekladových aktivít v slovenskom kultúrnom priestore a podoby ich fungovania v ňom [Translation as a Part of the Cultural Space History II. Facts, Phenomena and Personalities in Translation Activities in the Slovak Cultural Space and the Forms of their Functioning], and by UGA, under grant No. II/25/2017 Sondy do dejín audiovizuálnej translatológie na Slovensku [A Survey of Audiovisual Translation Studies History in Slovakia].

______

- This working definition is derived from Popovič’s semiotic-communicative definition of translation, which can accommodate the semiotic specifics of intersemiotic translation (as defined by Jakobson 1959). Thus, according to Popovič, translation is “[r]ecoding a text during which its stylistic model is constructed. The translation is a stylistic (topical and linguistic) model of the original and it is in this sense that the translational activity is an experimental creation” (Popovič 1975: 19).

- Texts that deal with linguistic aspects of AVT have been included in the Bibliography and are often referred to by Slovak AVT scholars (e. g. the works of D. Tarcsiová or Š. Csonka on sign language) as far as they are (also) relevant for the understanding translation-related qualities of AVT. On the other hands, linguistic studies of AVT phenomena that do not take stock of the specifics of audiovisual communication have been excluded from the corpus.