Valeria Giordano

University of Rome Tor Vergata

valeriagiordano2@virgilio.it

Abstract

Taboo is a Polynesian word for any number of religious prohibitions which forbid specified behaviours, usually under the threat of punishment. Many taboos of this type involve offences towards the spirit world and religious customs. For this reason, taboo terms and coarse language are either suppressed or severely reduced in the Italian dubbed versions of American TV series, especially when referring to both religion and sex. Starting from a preliminary isolation of the cultural elements generating taboos connected to sex and religion, the paper discusses some differences between the US and Italy. Furthermore, the study offers a glimpse into some issues concerning obscenity, religious taboo, oaths and swearwords and discusses the sexuality of Christ between profanity and blasphemy as the ultimate taboo and point of connection between the taboos being analysed. The considerations expressed in the present paper come from a discrete script analysis and from a comparison of the original version with the one translated into Italian. The comparison is important to describe the different translation strategies followed in the presence of sex-related talk in religious issues. Some critical examples are provided.

Introduction

A taboo is something a culture considers forbidden, although it is not necessarily religious in nature. Sexual morality varies greatly between cultures and society establishes standards of sexual conduct according to which sex may have either a negative connotation or is considered the highest expression of the divine. Catholic sexual morality distinguishes between activities that are practiced for biological reproduction, allowed only when in formal marital status, and others practiced for sexual pleasure sought for itself, isolated from its procreative purposes. Fornication, masturbation, lust, pornography, are considered immoral. Italian sexual morality is generally based on these principles by which Catholic believers can evaluate whether specific actions meet these standards. For this reason, matters pertaining to sex and religious issues in translation from English into Italian are likely to create more translational difficulties than others involving the two concepts separately. The idea of otherness in Western societies is often connected with the breaking of existing taboos; these apparently conflicting positions provide a stimulating focus for research across a wide range of academic fields, especially translation. Therefore, the examination of taboo reinforcement or debasement is essential in progressive, multicultural societies, governed by institutions such as moral correctness and cultural and personal upbringing.

Historically, the word taboo comes from Polynesian1 and is used to describe some religious prohibitions forbidding specified behaviour, usually under the threat of punishment. Some taboos are so offensive that they are also illegal: paedophilia for instance, but also some sexual practices which are believed as ordinary rather than perverse, such as sexual pleasure in pain (as occurs in masochism and sadism), might be taboo. Many social taboos of this type involve offences towards the spirit world and religious customs, but ‘benign’ taboos also exist. In previous decades, openly recognizing homosexuality was also taboo. In general, we can observe that sexual taboos are evolving. In contemporary society there are few taboos left. Today’s teenage sexual education would have shocked and embarrassed many married couples in the past. Fantasies are now discussed freely, and films have become more explicit. Premarital sex is virtually the norm and homosexuality, sadomasochism, group sex, wife-swapping, can all be discussed in polite society now. More concern is registered over someone making a value judgement against such practices than whether someone indulges in them.

The chosen corpus was selected to explore the idea of religious taboo and swearwords together with its respective Italian dubbed version in a TV show, The Secret Life of the American Teenager, which seemed to have all the potential to deliver a powerful message on the consequences of teen sex and the need for responsibility. Starting from a preliminary isolation of the cultural differences between Italy and the US, the study provides comments on the linguistic texture of the original audio-visual text and discusses some of the choices operated in its final translation for dubbing. The research hypothesis is that, in the comparison between the American and the Italian cultural values, Italy is a country in which religion and swearwords are two separate worlds; these ideological considerations end up shaping and affecting professional practice. The issues expressed in the paper find evidence in the script analysis provided. The investigation pays attention to the impact of ideology on the final product and provides examples in which ideological considerations manifest themselves in professional practice. This paper is also intended as a basic cultural background on which to build translation strategies involving taboo and religion from the source culture to the Italian target culture.

Sex and religion in The Secret Life of the American Teenager

The Secret Life of the American Teenager is one of the many contemporary shows portraying taboos on national television, the most evident being teen pregnancy. It is categorized as a teen drama aired on ABC Family and renewed for five seasons until summer 2013. The show also includes some ‘deviant’ behaviour in general, intended as attitudes going against certain cultural norms: drug addiction, abortion, abusive and alcoholic parents, attempted rape, student/teacher relationships, gay marriage and mental instability. It is intended for the target audience of teens and their families who are trying to cope with a culture where teenagers are sexually active. The general tone is educational, since it shows the negative consequences of promiscuous sex. Materials for discussion are taken from the fifth season of the series. The show primarily focuses on the character of Amy, a 15-year-old student who falls for what might be the perfect guy but gets pregnant from a less-than ideal teenager. First, the show provides some useful elements about American teen culture which could be of great interest when examining translation issues and the dubbing of culture-specific elements, but one of the most important parts is the transposition of taboo elements, especially when referred to sex and religion. It is quite hard to balance the general didactic tone of the show with real dialogues between teenagers, even in the original, and the translation in Italian often deals with specific issues pertaining to Italian culture, such as religion and Christianity representing a tangible taboo.

The series shows the effect of behavioural choices of teens and the channel ABC Family intended to air at least one public service announcement during the première, urging parents to talk to their children about sex. General reluctance of parents to address the issue (Schuster, Eastman, and Corona 2006) and US government-approved programs which leaned so heavily on abstinence (Stidham Hall, McDermott Sales, Komro and Santelli 2016) cause the media to fill this informational function and become sex educators. The general attitude portrayed in theory seems to be that what is seen on TV does not alter teens’ behaviour; young women, although they may enjoy a show about pregnancy, do not necessarily imitate such behaviour. On air, teen pregnancy is not necessarily viewed as negative: it can be considered acceptable, if there is something to be learned from it. For American television producers, however, restrictions on these themes are creatively reminiscent of the Hays Code2, where any character who commits unlawful behaviour in a film must be punished in the end. By the 1960s the code was no longer followed, but it sometimes still casts a shadow on the current censorship guidelines when cultural taboos are analysed. Both American television and the Italian one appear to be free from any moral constraint. However, one bastion of privacy and shame remains, that is the subject of religion and sex. Italian rights for the show were bought by Disney, and this data has proved to be significative for Italian dubbing.

Obscenity, religious taboo, oaths and swearwords

Determining what is obscene could be a “timeless preoccupation”. According to Melissa Mohr (Mohr 2013), defining the idea of obscenity is as problematic as the search for words that adequately express a relationship with the divine. Religions have their own set of taboos. Offending God is the most obvious, but there is also a variety of taboos impacting daily activities. Swearing is considered an act that forges a bond with a higher authority but at the same time also breaks it. In both cases, certain words, especially sex talking, are endowed with the power to shock and scandalise. Some religions, and therefore cultures, consider various sexual practices as taboo. Homosexuality, incest and bestiality are inherently taboos for followers of the Christian Bible. Among Catholics, sex of any kind is taboo for religious figures, but not for married general believers. Sex and religion are intricately linked, and this is explicitly expressed in the words that aim to underline this link. Obscenities and sex talking refer to earthly matters and remind us that we have bodies, burdened with physical functions; oaths point at heaven, reminding us that, besides a body, we have a soul.

There are few realms of human experience other than sex in which religion has greater reach and influence. The role of religion to prohibit, regulate, condemn, and reward, is unavoidably prominent in this field. Sex as a topic of conversation in movies or television can make people uncomfortable in all cultures, but its discussion varies in difficulty. The Hays Code enumerated several key points known as the “Don’ts” and “Be Carefuls” (Lewis 2002: 301-2) and pointed out that some taboo issues were not to appear in pictures, irrespective of the way in which they were treated. This list included many things: from drug traffic to any reference to sex perversions, which surprisingly included interracial sexual relationships; licentious or suggestive nudity, ridicule of the clergy, offence to any nation, race or creed. One of the most interesting prohibitions of the list, maybe the most important one as it was named first, was: “Pointed profanity – by either title or lip – this includes the words ‘God,’ ‘Lord,’ ‘Jesus,’ ‘Christ’ (unless they be used reverently in connection with proper religious ceremonies), ‘hell,’ ‘damn,’ ‘Gawd,’ and every other profane and vulgar expression however it may be spelled” (Lewis 2002: 301). This peculiar interest in religious matters finds its origin in the creators of the code: a Jesuit priest and a Catholic layman, both particularly worried about the effects of sound film on children, considered susceptible to their allure. The general principle was that a film should not lower the moral standard of those who watch it; that a film must depict the correct moral lifestyle and must not show any sort of ridicule towards a law or create sympathy for its violation. It was also based on a list of items which could not be depicted. Nevertheless, some restrictions, such as the ban on homosexuality or the use of specific curse words, were never mentioned explicitly but clearly understood. In this sense, the code was intended to determine what could be shown on screen, but also to promote traditional values in which unaccepted social behaviours, such as sexual relationships outside marriage (which were not to be portrayed as attractive) were to be presented in a way that included final punishment. The code did not admit any sort of ambiguity between acceptable and unacceptable behaviour. Its deep moral significance was unquestionable.

By the 1950s, American culture began to change. A boycott by the National Legion of Decency no longer guaranteed a film’s commercial failure, and several aspects of the code had slowly lost their taboo quality. In 1956, areas of the code were rewritten to accept subjects such as miscegenation, adultery, and prostitution. By the 1960s, the original code was replaced by a list of eleven points and eventually abandoned. Even though a direct code about taboos is now missing, their use sometimes continues to create problems when two or more cultures are compared. Christians try to make the nature of unprohibited sex very specific because the Bible seems to encourage it (go forth and multiply). In this sense, Hollywood is considered something which hypocritically over-sexualises everything and then condemns it with ratings (which nowadays substitute the Code). However, multi-ethnic America permits multiple discourses about the variety of religions professed, allows priests’ marriage because several religions permit it, while Italy remains conservative in its way of dealing with religion, so that when religion is mixed with sex the degree of the taboo shows its maximum influence.

Sex and religion in Italy: if you like it it’s a sin!

Religion is about control (Ellwood 1918). Religions institutions maintain temporal power by controlling sexual freedom: the Church claims that sex should only occur within marriage, because pregnancy might ensue, and it involves responsibility towards the child. Abortion and contraception threaten the control over sex life by making responsible extramarital sex a realistic possibility and are therefore condemned. On the other hand, sex is a basic human drive and can be considered a need like food and water (Maslow 1943)3.

A TV show speaking freely about these issues could cause problems when transferred into a culture subjected to a stronger religious control over people. Even though we live in an age dominated by secular thinking, the possibility of non-religious marriage and more liberal approaches to sex persist in the name of traditional values that are slightly more important in Italy than in other countries, where multi-ethnicity is the rule and not the exception. On the contrary, Wicca and many other Pagan religions accept sex as something that should be enjoyed as the God and Goddess intended. The sexual act entails worship of the deities.

Another important issue connected to sex and religion is the idea of guilt about sexual enjoyment, which reinforces the concept that religion is all about power, control and prejudice (see again Ellwood 1918). If Christians accept sex only as a means to procreation, enjoying sex for pure pleasure is a sin and, as such, it is forbidden. Public sexual behaviour is frowned upon in society, and fear of disapproval and condemnation prevent from having an open sexual behaviour: the offender might be condemned and isolated from society. Believers who lapse into sex offences consider themselves as sinners and experience a sense of guilt and personal failure, since their behaviour fails to enable them to live up to the high moral standards they proclaim. Their sex life ends up becoming the tangible proof of the decline in the authority of the religious institutions and their tradition. Christians practising birth control in ways the Church explicitly forbids are people contesting the Church’s authority on moral questions; this causes a moral struggle between their sexual desires and their will to adhere to the rules imposed by their religion. Sexual morality issues cause teenagers to stay away from the Church because of the social stigma they may be subjected to in practising their sexuality freely. In Italy, the Church teaches that all sexual pleasure out of marriage is sinful, with no confusion at all among religious institutions and communities. This causes important cultural issues when comparing the cultural systems of the US with the Italian one.

Between profanity and blasphemy: the sexuality of Christ as the last taboo

The word taboo is strictly connected to the idea of profanity and is a connection between the taboos of sex and religion. Indeed, the term profane originates from classical Latin profanus, literally meaning before the temple. Its original meaning is of blasphemous profanity: either desecrating what is holy or with a secular purpose (secular being intended here as non-religious and not sacred). Profanity in language is socially blamed, offensive and impolite. It can show desecration or intense emotion and represents secular indifference to religion, while blasphemy is a more offensive attack on it or a direct violation of the Ten Commandments.

One of the most interesting taboos of religion and sex which perfectly fulfils the connection between profanity and blasphemy is discussing the sexuality of Christ. One of the critical examples provided in this study involves this strong taboo which exists in Catholic cultures as the result of attempts to establish and defend strong ethnic, religious or institutional confines, by which harsh penalties on forms of sexual behaviour stepping over boundaries are imposed. Taboo operates at an emotional level and thinking about Christ having sex, even if the idea reinforces his humanity and consequently the link to God in the earthy epiphany he represents, is something horrifying for those who believe in Christian values. If Jesus were human, it would be quite probable that he experienced one of the most basic and important human traits such as sex. The supposed virginity of Jesus is under debate by experts: it is clearly stated in the Bible, that Jesus did not sin (2 Corinthians 5:21; 1 Peter 2:22)4. The dispute arises on whether Jesus could have sinned or not. Those who hold the position of ‘impeccability’ argue that it was not possible for Jesus to sin, while the position of ‘non-impeccability’ holds that Jesus could have sinned, but did not do so, because in himself full deity and full humanity melt into one person and are thus indivisible. Believing that Jesus could sin means believing God could sin. This position maintains that, although Jesus was fully human, he was not born with our own sinful nature. He certainly was tempted in the same way we are, as temptations were confronted by Satan. Indeed, Magdalene’s shock value consists in the simple fact that highlighting her presence in the life story of Jesus changes its perceptive. It forces us to think differently about the Saviour. He who restored human nature to sinlessness cannot be shamed by the sexual factor in his humanity. Many people of faith consider the notion that Jesus was married to a woman who bore him children to be the ultimate sacrilege that one might direct against him. To them, the sexuality of Christ is totally incompatible with his divinity, but this was not always the case among believers. In previous times, the sexuality of Jesus was widely regarded as proof that Christ had assumed the full guise and burden of humanity. In general, Christians do believe that there are no places where God is not present. However, there are certain taboo areas which are commonly considered as far from God. In the gospels, Jesus is seen as going into those places considered godless and taboo and dispelling old fears and superstitions by taking God’s presence into them. Thus, we see Jesus entering the lives of the sick, touching lepers, curing a woman struggling with menstruation, dining with prostitutes, and ultimately dying on a cross. All of these were considered unholy, unclean places. We now live in a culture which has essentially no religious, moral, or psychological taboos around sex and has little, if any, fear of it. Sex has both been emptied of superstition, false fears and false taboo, and is now devoid of most of its sacredness, mystique, depth and soul. Regarding Christ as the virile saviour is a touchy issue which should be handled discretely because it could easily be cause of irreverence or blasphemy. Catholic Italy does not even remotely suggest that Jesus, fully incarnated in humanity, may have engaged in sexual behaviour. A crucial distinction also emerges in the theological dispute: that is, between the claim that Jesus had sex with Mary Magdalene, and the one that he fathered her children, the first hypothesis sees Christ performing sexual intercourse, but not for the purposes of procreation or in a wider vision of sex performed within marriage (and not considered as a sin because of this). If Jesus was not married or did not have any children it means that he engaged in sexual intercourse, not to procreate, but for pure pleasure. Therefore, the last taboo is not about sexual intercourse but about the pleasure in the sexual act. The debate around the sexuality of Jesus is focused on procreation, rather than on pleasure. The critical example provided shows how this theological dispute can affect translation practice when such a taboo emerges in the source text.

Translation and taboo in previous research

Every society is based on its system of cultural values. Social life includes language use and is governed by socially shared norms, establishing appropriate behaviour; rules that are “clearly linked to the social setting, the sex, the age, the status of the speaker, and the audience” (Spears 1982: Intro XIII). The role of culture in translation is inevitable: translating involves at least two languages and two cultural traditions, hence different conventions and norms (Toury 2004). Therefore, audio-visual translators should utilise a variety of strategies to solve the intricate task of translating taboo. Issues regarding censorship and audio-visual translation of imported fictional products in Italy have been discussed (Azzaro 2006) and have revealed that taboo terms and coarse language are either suppressed or severely reduced in the Italian dubbed versions (Pavesi and Malinverno 2000: 77-82). Regarding Italian dubbing, other studies (Chiaro 2007; Bucaria 2007) claim that it is quite the norm to regulate the level of obscenity which often characterises American film language, especially with vulgarity, very often not translated or frequently mitigated. Some scholars (Zanotti 2012) also pointed out that such mitigation and censorship strategies are particularly frequent when dealing with films for youth. This type of censorship is sometimes self-imposed by the translators themselves, to make the adaptation acceptable to the board of censors and the Italian audience (Zanotti 2012: 366). However, in many cases translators follow dubbing instructions of the production companies which sometimes focus on enlarging profits and providing a more commercial product for the Italian market. Moreover, some scholars (Ranzato 2010, Beseghi 2016) have recently pointed out that the patronage and the commissioning network play a crucial role in the degree of freedom in translating swearwords. In the present study mitigations and omissions appear to be more frequent when the religious taboo is involved.

Research findings and results

Explicit taboo references are present in all the original versions of The Secret Life of the American Teenager; however, the analysis of their Italian dubbed versions considered in this study reveals a lack of homogeneity in the adopted translation strategies. Lack of homogeneity in the translational behaviour is not ascribable to different ideologies on the part of the translators, or on censoring policies imposed by commissioners. Different behaviours are observable in the very same episode, implying a basic inconsistency in the adopted translation strategies, or at least a dissimilar response of the dialogue writers to the strict indications imposed on them by the patronage. This is due to the categorization of taboos in certain fields between the two cultures and happens when the target culture audience is expected to be uncomfortable with some cultural elements in the source text.

The analysis of the present study confirms this tendency towards inhomogeneity. In the case of taboo elements about religion and sex, the choices made by dialogue writers might be very different from the ones in the source text, since the translation would be rejected if it conserved the taboo element, in contrast with the patronage. The patronage’s main concern is that most audio-visual works in English abound in vulgarities that may offend an Italian audience. As hinted, issues regarding the translation of religious taboos in Italy represent a problem: elements from the original might be considered immoral, disgusting and indecent when sex is connected to religion, especially when such TV products are watched by the entire family, minors included. In this case, Italian dialogue writers make extended use of euphemistic translation, used to represent something unpleasant in a less offensive language. According to some scholars (Allan and Burridges 1991), euphemisms are used as an alternative to an unpleasant expression, but sometimes they are claimed by the patronage to be insufficient to mitigate the taboo.

The taxonomy of taboo elements detected in the corpus basically consists in three core points:

- the word in the source text is not a taboo in L2. This permits direct translation (e.g. interracial marriage, which has its historical roots in American history and consequently does not have the same importance in Italian culture);

- the term is a taboo in both cultures, leading therefore to comparative strategies;

- the word which is not considered a taboo in L1 might be as such in L2 (e.g. celibacy and chastity among Italian priests differ from US culture, creating a potential taboo).

This implies that the translation process is quite easy and direct in the first possibility but needs an accurate reflection in the remaining ones. The translator is asked to operate precise choices to render the meaning and the feeling of the taboo word, and when this is not possible, since it would cause a cultural shock, the translator will focus on a similar and acceptable meaning of the word. Unfortunately, Italian translators are not free to operate these choices without the intrusion of the patronage and they are often forced to select the apparently simplest choice, that is radically removing the taboo element. Nevertheless, the taboo is often a key term in the source text. If omitted, the target text risks to be distorted. Also applying a method in which the taboo is maintained, no matter what, could not be considered a winning strategy tout court, because it could be often be embarrassing to the audience. Another way of translating a taboo term is substituting it with another term in L2, and this often implies a distortion of the target meaning as well, causing confusion or even absurdity and nonsensical translation for the target public. Significant examples of these substitution are provided in the following paragraph. On these bases the possible detected strategies are omission, conservation and substitution. All of them entail significant damage to the source text. A good compromise resides in the key word euphemism. Some euphemisms are intended to refer to touchy taboo topics in a polite way and have the function to mask profanity preserving the taboo content or word without upsetting the viewers and protecting them from possible offence (Linfoot-ham 2005: 228).

Examples from the script analysis: consequences of total omission and manipulation

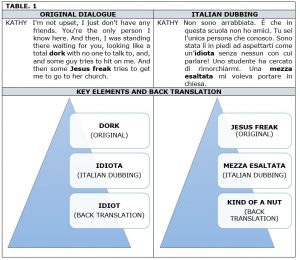

This concluding paragraph pays attention to the impact of ideology on the final product and provides critical examples on the topic of translating sexual and religious taboo in dubbing, where ideological manipulation manifests itself in professional practice. What generally emerges after a deep scanning of the corpus is that direct allusion to religion is mitigated. Almost every reference to Jesus is eliminated also when appearing in the de-semantised exclamation “Jeez!”; the dialogue writer decided to avoid euphemism and to use a total omission of the reference, also in dialogues in which a certain emphasis on the exclamation would have reinforced the taboo and semantised it again, especially when pronounced by the character of Adrian Lee, the symbol of every negative model in terms of sexual behaviour and morals in general, in direct opposition to the angelic character of Grace Bowman. Grace is a perky 19-year-old girl, the school’s head cheerleader and a devout Christian, whereas Adrian is a 20-year-old majorette with a reputation for being promiscuous. Adrian comes from a broken home while Grace comes from an apparently perfect family, even though she decides to have sex with her boyfriend Jack. After this encounter, Grace learns of her father’s death in a plane crash and feels guilty that the crash happened while she was having sex, and wonders if, in some way, her father’s death was a punishment for extramarital sex. In this sense she embodies the Christian who has indulged in the pleasures of sex and received a punishment for this. She takes a while to recover from this idea and then tries to compensate for her feelings by pledging to wait to have sex again until marriage, even organizing a group of teenagers to embrace abstinence. Adrian, on the other hand, embodies all the taboos we have previously mentioned: promiscuous sex, teen pregnancy, abortion, casual relationships, feelings of anger, mental instability. Grace experiences a character evolution through pain and suffering because her sexual behaviour results in pregnancy. She decides to keep the baby after she had considered an abortion, but she receives another punishment, since the baby is stillborn. She gives her child the symbolic name of Mercy and after this she experiences a moral evolution, though she remains a character deeply connected with the idea of taboo breaking and a scandalous figure. All these moral issues must be seriously taken into consideration when rewriting dialogues for the characters of Adrian and Grace in Italian; a reasonable strategy from the translator’s point of view should be to leave the religious references exactly the way they are. An indiscriminate mitigation of taboos eliminates all the language characterization of different personae in the source language and the motivation by which this manipulation is carried out is not necessarily connected with actual Italian social needs. Sometimes the impact of the religious taboo on Italian culture is so violent that when it appears in combination with a vulgar element in the source text it often undergoes a total omission. The reason for which the exclamation Jeez! was to be eliminated is that there is no correspondent in Italian that could be considered a euphemism. The original interjection, which is a substitution for Jesus Christ!, portrays irritation, shock, annoyance, disappointment. Although usually expressing grief, it can be used with much versatility, including the expression of exaltation. Since Italian does not contemplate a euphemism for this, it would still be considered taking the Lord’s name in vain. This indication of mitigating religious references seems to derive from the Hays Code, but in Italian it is part of the regulations set forth by Walt Disney Television Italia (Disney Italia from now on)5. Dialogue writers receive informal indications as to what is to be included/omitted from the final product. Sometimes the total omission of the religious reference does not cause significant damage, since the dialogue writer chooses other expressions to convey the same emotional meaning, though mitigating vulgarity or the presumed blasphemy inherent to simply nominating God or Christ. Please observe the dialogue and its translation in the following Table 1:

In the example the swearword Dork is down-toned into Idiot. The translation may be considered appropriate, since in Italian the word Idiota is suitable to address a nerdy or socially inept person, as well as its more literal meaning (an unintelligent or unwise person); further we observe that Jesus Freak is translated with mezza esaltata (kind of a nut), with a total omission of the religious reference. The original is a slang term to indicate someone who is obsessed with converting others to Christianity, exactly like Grace’s character. While the specificity is lost, there is a general similarity to the original text. However, there are some other cases in which being forced to eliminate the nomination of God can provoke a nonsensical portrayal of the original content. Please observe the example in Table 2:

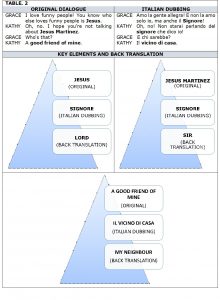

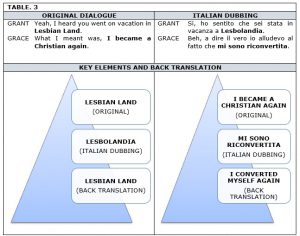

In the final translation imposed by the patronage6, Jesus is substituted with the Italian correspondent of Signore (Lord) as a euphemism to mitigate the humour with which Grace is referring to Jesus Christ. But when Kathy mockingly pretends she is referring to her friend Jesus Martínez, the reference to Jesus was omitted again, this time with the pun signore (sir), causing a total loss of the humour in the line but also a consequent nonsensical reply (provided in the back translation). In this example the damage produced in omitting the name of Christ can be considered relative. In other examples the damage risks to be significantly higher. According to what Disney Italia initially demanded, total omission was imposed not only to the specific name of God or Jesus, but also to every reference to a specific religion: in most cases the word Christian was translated in the final adaptation with the general term credente (believer), whereas it was left as cristiano (Christian) in the preliminary translation. A comparison with other episodes adapted by different dialogue writers shows that in some cases the patronage orders were respected with no exceptions, while in others they were ignored, thus revealing a lack of a univocal translation strategy for these problematic elements. Please observe Table 3:

In this example the substitution of Christian is innocuous and does not produce any damage. This might be a case of self-censorship based on the indications received from the patronage. The allusion to Lesbian Land as a reference to Grace’s kissing Adrian, the consequent rumours and her self-doubt about her sexuality were considered inappropriate to appear in the same dialogue in which Grace is renewing her faith. The adopted solution eliminates any reference to specific religion as demanded, but everyone knows that the religion involved is Christianity, especially anyone who knows Grace. Despite the substitution, the general sense of the dialogue is preserved. However, we can prove that a lack of strategy may cause a lot of damage when indiscriminate manipulation occurs without any criteria other than fortuity. Sometimes the manipulation coming from external influences such as the indications of distributors can heavily affect the final content of the translation. Please observe the following translation in Table 4:

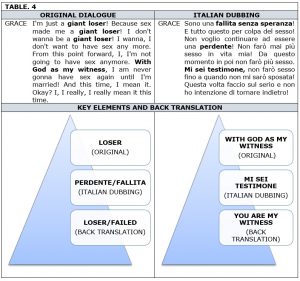

We may notice that in the final dubbing what gets lost is:

- the slang form to translate giant loser (sfigata) since in Italian its root word is closely connected to a slang term for female genitalia (figa, literally meaning pussy). The Italian gergal version denotes that s/he who remains without sexual activity is considered a loser (prefix s+figa=without pussy) and so a blander term was chosen (fallita/perdente);

- a direct quotation of the movie Gone with the wind in one of its most famous quotes (in Table 5) that adds a comic tone to the entire dialogue.

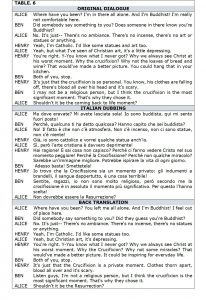

The final choice was made by the dubbing director because of the imposed diktat to remove every reference to God. In this case the dialogue writer proposed an exception to this indication since it was justified with the direct quotation of a famous movie, whereas the dubbing director opted for a choice of acquiescence to the instructions, thus affecting the whole general comic tone of the gag and the loss of the direct quotation of a famous film. Inhomogeneity in translation strategies could also derive from the modality the dialogue writer proposes the issue to the supervisor: if reasonable motivations for a certain translation strategy are presented through the use of footnotes or by direct contact with the patronage, the manipulation process could be reduced and the resulting translation could be a compromise between the conservative attitude of the translator aimed at preserving the original meaning of the term, including its primary impact on the public, and supervisors’ concern regarding the audience’s shock. Please observe Table 6:

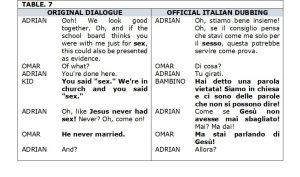

The dialogue is taken from the episode #103, that is about a church service which causes some drama when a variety of people who don’t usually attend (including Adrian) decide to. In the sequence the supervisor authorized the preservation of some reference to religion, this contradicting the strategy of omitting any reference to specific religion or substituting with euphemisms used so far. Otherwise the entire sequence would have been eliminated if there was no way of finding a non-specific correspondent to Christian rituals of Resurrection and Crucifixion. The conservation of the reference was discussed with the supervisor and only very few changes were produced, mainly for lip-sync motivations. On the other hand, the following sequence (Table 7), appearing soon after in the episode, undergoes radical changes. It involves the controversial character of Adrian. Her presence in church is certainly atypical and causes some problems with her rebellious spirit.

The sequence was highly manipulated in most of its elements. Starting from what the child says, it was considered scandalous for a minor to utter the word sex; hence the substitution with the generic parola vietata (forbidden word) or parole che non si possono dire (words which must not be said) in church. The most important part of the sequence is indeed Adrian’s reference to the sexuality of Christ for which the supervisor imposed a moral judgement that was absent in the original script. So, in Adrian’s genuine question Oh like Jesus never had sex? the explicit reference to Christ’s sexuality was omitted, but the chosen translation adds the meaning of non aveva mai sbagliato (He never made a mistake), according to which sex is wrong and so it is unbelievable to name his sexuality in a Catholic country like Italy, in which he is supposed retained to have died a virgin. Also, the theological dispute about Christ’s marriage hinted at in Omar’s reply was considered unthinkable and was totally omitted, although pertinent.

Concluding remarks

This contribution aimed to explore some linguistic and cultural issues related to the dubbing of taboo words referred to both religion and sex. Some critical examples have been selected for their translation analysis as significant cases coming from a TV show dealing with taboo topics, but in which some words are even impossible to be chosen in the Italian version, including naming God. The taboos inherent to sex and religion have been shown to be both suppressed or drastically changed, thus revealing the persistence of the taboo in the Italian culture and confirming the research hypothesis. In the examples we have observed different effects of manipulation on the final dubbed dialogue. Sometimes these translations are subject to savage manipulation by the patronage when they do not respond to a codified translation strategy or when dialogue writers are unwilling to operate a self-censuring process according to instructions. An indiscriminate mitigation of taboos affects language characterization in the source language and even adds moral meanings that are not present in the original. The conclusions we have come up is that manipulation is linked to the patronage and not necessarily connected with actual Italian social needs. Several other examples of religious taboo mitigated or omitted can be found throughout the corpus and the adopted translation strategies are non-univocal. This phenomenon can be caused by multiple factors: the same dialogue writer could have had different levels of self-censorship according to what may be considered as scandalous; there is often more than one dialogue writer for different episodes and their interpretation of the diktats could be more or less rigorous in each case, since it is based on unofficial unwritten indications. It would be interesting to further develop these notions on a wider scale to better understand these semantic differences.

References

Allan, Keith and Burridge, Kate. 1991. Euphemism and Dysphemism: Language Used as a Shield and Weapon. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Azzaro, Gabriele. 2006. Four-letter Films. Taboo Language in Movies. Roma: Aracne.

Beseghi, Micòl. 2016. “WTF! Taboo Language in TV Series: An Analysis of Professional and Amateur Translation”. Altre Modernità. Special Issue. Ideological Manipulation in Audiovisual Translation(2): 215-31.

Chiaro, Delia. 2007. “Not in front of the children? An analysis of sex on screen in Italy”. Linguistica Antverpiensia(6): 255-76.

Doherty, Thomas. 1999. Pre-Code Hollywood: Sex, Immorality, and Insurrection in American Cinema: 1930-1934. New York: Columbia University Press.

Ellwood, Charles A. 1918. “Religion and Social Control”. The Scientific Monthly Vol. 7(4): 335-348. Published by: American Association for the Advancement of Science. http://www.jstor.org/stable/7045. Accessed on: 24-02-2018

Lewis, Jon. 2002. Hollywood v. Hard Core: How the Struggle Over Censorship Created the Modern Film Industry. New York: NYU Press.

Linfoot-ham, Kerry. 2005. “The linguistics of euphemism: A diachronic study of euphemism formation”. Journal of Language and Linguistics 4(2): 227-63.

Maslow, Abraham. 1943. “A Theory of Human Motivation”. Psychological Review. 50(4): 370-396.

Mohr, Melissa. 2013. Holy Sh*t. A brief history of swearing. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

Pavesi, Maria and Malinverno, Anna Lisa. 2005. “Usi del turpiloquio nella traduzione filmica”. In: Taylor, Christopher (ed.), Tradurre il cinema. Trieste: University of Trieste, Dipartimento del linguaggio. 75-90

Schuster, Mark A., Karen L. Eastman, and Corona, Rosalie. 2006. “Talking Parents, Healthy Teens: A Worksite-Based Program for Parents to Promote Adolescent Sexual Health.” Preventing Chronic Disease 3(4): A126.

Smith, Sarah J. 2005. Children, Cinema and Censorship: From Dracula to the Dead End. London: I. B. Tauris.

Spears, Richard A. 1982. Slang and Euphemism. New York: Signet Book.

Stidham Hall, Kelli, McDermott Sales, Jessica, Komro, Kelli A. and Santelli, John. 2016. “The State of Sex Education in the United States”. J Adolesc Health. 2016 Jun; 58(6): 595–597.

Toury, Gideon. 2004. “The nature and role of norms in translation”. In: Venuti, Lawrence (ed.), The Translation Studies reader. 2nd edition. London and New York: Routledge. 205-18

Zanotti, Serenella. 2012. “Censorship or Profit? The Manipulation of Dialogue in Dubbed Youth Films”. Meta 57. Special Issue. The Manipulation of Audiovisual Translation(2):351-68.

______

- Biggs, Bruce. “Entries for TAPU [OC] Prohibited, under ritual restriction, taboo”. Polynesian Lexicon Project Online. University of Auckland. https://pollex.shh.mpg.de/entry/tapu/. Accessed on: 24-02-2018

- The Motion Picture Production Code, popularly known as the Hays code after Hollywood’s chief censor at the time, Will H. Hays, governed the moral censorship guidelines of most United States motion pictures released by major studios from 1930 to 1968.

- Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is often portrayed in the shape of a pyramid with the largest, most fundamental needs at the bottom and the need for self-actualization and self-transcendence at the top. Physiological needs are the physical requirements for human survival. If these requirements are not met, the human body cannot function properly and will ultimately fail. Physiological needs are thought to be the most important; they should be met first and they include sex.

- Every quotation from the Bible is to be found here: https://www.biblegateway.com

- Italian holding company operating in the field of TV industry. It produces Italian Disney channels and TV series for The Walt Disney Company Italia, the first Disney branch in the world.

- I was the translator hired by the dialogue writer for most of the episodes included in the corpus chosen in this study; this allowed me to analyse the entire process of transposition and to know the reasons behind the translation strategy used.