Mgr. Jana Ukušová – Prof. PhDr. Peter Kopecký, CSc.

Constantine the Philosopher University in Nitra, Slovakia

jana.ukusova@gmail.com, pkopecky@ukf.sk

Abstract

The issue that is being examined in this paper belongs to the field of community interpreting, and more precisely, it relates to sworn interpreting within the context of judicial and police environment. It is theoretically anchored in the work of A. Klimkiewicz (2005) and her model of community interpreting as trialogic communication (professional – client – interpreter) as well as the works of D. Gile (2009) and É. Fusilier (2010). The paper examines the hypothesis that in the light of current migrant crisis in Europe, sworn interpreters find themselves also in the position of social and humanitarian workers having ethical and moral responsibilities. This is approached on the basis of real-life situations which are analysed from the standpoint of interpreter’s role and competences. Interpreters’ role becomes even more complex in case of children involvement in the process, (K. Balogh – K. Salaets, 2015) in the sense that he/she shouldn’t provide interpretation during a hearing of a minor unless a UNHCR representative or a representative of a competent district office of social affairs is present. If he/she does, he/she is involved in law-breaking.

Rather than presenting a general and theoretical approach to interpreting, the paper reflects a more context-based position. The methodology consists mainly of phenomenological and empirical approaches; we provide and analyse specific real-life cases from the police and investigators environment and the presence of interpreters when dealing with migrants. The stress is also put on the flexibility of deploying interpreters and the related risks which may arise when the deployment flexibility is bad, and interpreters are called too late. Last, but not the least, it also indirectly points to interpreters’ education, more specifically to educating and preparing interpreters who will master other languages that the ones used so far to be able to respond to new challenges and needs in providing interpreting services to migrants. In order to support this emerging necessity, we provide the following examples. The first one relates to detained juvenile Moldavians who refused the services of Slovak-Romanian interpreters, assuming that in Slovakia, there isn’t enough qualified interpreters working with the Romanian language. The second example has a rather peculiar nature; at Bratislava airport (Slovakia), a Nigerian citizen, who was supposed to smuggle drugs by inserting them into his rectum, was detained. He refused a help of an English interpreter, claiming that he speaks only the dialect of his country of origin…

Introduction

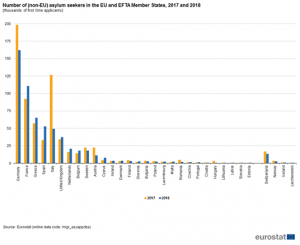

Europe is probably on the brink of its greatest crisis concerning the migration of people since the Migration Period. In the last decade, no region is undergoing such a profound ethno-cultural mutation as Europe. Based on the following diagram developed by Eurostat (2019), in 2018, the numbers[1] of asylum seekers were peaking in Germany (162 000 applicants, 28 % of all first-time applicants in the EU Member States), France (110 000 applicants), Greece (65 000 applicants), Spain (53 000 applicants), Italy (49 000 applicants) and the UK (37 000 applicants).

Diagram 1 Number of (non-EU) asylum seekers on the EU and EFTA Member States in 2017 and 2018[2]

This article examines a part of a social consequences of this mutation and their impact on some elements involved in the process of receiving migrants, including roles of legal interprets and human capital development in Europe. We present the changing face of legal interpreting, with an emphasis on selected contemporary humanitarian aspects.

This paper is based on our Slovak experience from the past four years, but we are sure that our experience and issues are not exhaustive. First, sworn interpreters find themselves nowadays also in the position of social and humanitarian workers. We provide an example of Romanian people smugglers, sentenced to three years’ imprisonment in Slovakia for having clandestinely smuggled Syrian inhabitants from Budapest (through Slovakia) to Munich. They committed a crime because they agreed to smuggle a dozen Syrians in their old van with open windows for a modest reward (Euro 200.00). Whereas the leader of the organised gang in Budapest, a Syrian himself, collected Euro 400.00 from each of his compatriots. Although the Romanian smugglers denounced him to the police during investigation, he remains free. Interpreters must not share their experience in the press or in specialised journals. However, it may be done in a more sophisticated manner so that the readers learn the background of legal interpreting. The position of interpreters becomes even more delicate because (as mentioned in the previous examples) they oscillate between their duty, conscience, national law, or even the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948). This is why the importance of legal interpreters is on the rise and why we must pay attention to the repeating phenomenon.

Methodology of the Paper

In the same way as extratextual factors influence the quality of the translated text during the translation process, various situational, mainly cultural, psychological, ethical, legal, and civilizational factors have an impact on the interpreting process, especially in sworn and community interpreting. It results mostly from differences[3] in legal codes between the EU Member States (Code of Criminal Procedure, Code of Civil Procedure, new EU legislation on refugee policy, different legal habits in the migrants’ home countries and in Europe, etc.).

In this paper, we provide real-life scenarios from the police and investigators environment and presence of community interpreters when dealing with migrants (the approach is therefore mostly empirical and phenomenological). Therefore, we present a perhaps atypical, but very up-to-date case study, designated not only to readers but also to other experts and interpreters working in the field of sworn interpreting. Based on our own experience, interpreters can find themselves in rather delicate situations. Each of these situations is viewed from the standpoint of the translatology[4] task (Müglová, 2009) that the interpreter has to accomplish. We analyse the required competences, a type of transfer and different kinds of speakers. Finally, we posit the question: What is the best approach that interpreters should adopt in these situations?

Community Interpreting: Genre Delimitation

As to the beginnings of community interpreting, the first efforts to grant community interpreting the status of a separate interpreting genre originated with the Critical Link Network, established in the 1990s at the University of Ottawa, Canada. A group of interpreters gathered together with people providing interpreting services in legal, social and health care sectors. This cooperation led to the organization of the first international conference on community interpreting in 1995. Since then, critical link conferences have been held every three years to promote establishment of standards related to the practice of community interpreting, encourage relevant research, and raise awareness about the profession of community interpreters.[5]

The variance of community interpreting lies not only in different names under which it can be found, such as public service interpreting (UK), cultural interpreting (Canada), liaison interpreting (Australia), contact interpreting (Scandinavia), dialogue interpreting, ad hoc, triangle, face-to-face, and bidirectional or bilateral interpreting (Gentile et al 1996; Carr 1997), but also in its scope.

Hrehovčík (2009, 161) claims that opinions on specific forms of community interpreting vary depending on authors and countries. According to him, the most controversial issue is whether community interpreting should also include such specific fields as court interpreting or conference interpreting. Roberts (2002, 162) argues that community interpreting differs from court interpreting and conference interpreting. In community interpreting, there are different objectives, different types of parties involved, different number of parties, different discourse used, different mode of interpreting, and differences in the directionality of interpreting. Several authors include court interpreting into community interpreting (Mikkelson 1996). For example, Giles (2009, 140) claims that public service interpreting (often referred to as community interpreting) includes court interpreting, medical interpreting, police interpreting, etc.

However, typical community interpreters, have not only a different role compared to court interpreters, but also a different degree of responsibility. Therefore, ad hoc service providers are often reduced to providers of non-professional interpreting services. These services may be rendered by whoever is immediately available such as medical hospital staff, family members (including children) or even other patients. Court interpreters, on the other hand, are in most countries specialized professionals offering assistance not only to defence or prosecution, but they are also active prior to the case (Hrehovčík 2009, 161).

As to the delimitation of the genre itself, Müglová (2009, 200-201) defines community interpreting as interpreting destined solely for individuals or for small groups of people who find themselves in a crisis. She distinguishes three types of these crisis situations:

- an existential crisis – migrants and refugees who left their country of origin for grave reasons and seek asylum;

- health issues – experienced by tourists or citizens of foreign nationality who reside in the territory of the given state and need medical intervention or hospitalization;

- unforeseen crisis situations – car accidents, criminal activity of foreign nationals, foreigners being victims of criminal acts etc.

Asymmetry: A Specific Feature of Community Interpreting

Community interpreting is provided in complex environments. Due to their multi-level hierarchy, the communication between the professional and his client presents several highly asymmetrical features that Klimkiewicz (2005, 210-211) summarized as follows:

- a major language – a minor language;

- knowledge, competence – not-knowing, ignorance;

- institution – individual;

- structures, laws, regulations – experience, feelings.

Klimkiewicz (2005) further explains that power relations in community interpreting are almost palpable since the client feels obliged to constantly explain himself and clarify certain information in the presence of the authority. This may cause that his way of expression might seem incomprehensible, intelligible, even barbaric and he can’t clearly answer questions that he was asked. This often happens particularly when interviewing illegal immigrants, nationals of countries with totalitarian regimes or struggling with traumatic events (such as war, military conflict, genocide etc.). The use of onomatopoeia, stuttering, exaggerated body movements are extralinguistic signs that make the other look radically different.

A Trialogic Communication

It is generally agreed that translators and interpreters play a role of mediators who enable interlingual communication. This role may vary to a certain extent depending on specific type of translation or interpreting. Based on Mikhail Bakhtin (1970) concept of the third, Klimkiewitz (2005) defined several aspects or functions of the community interpreter’s role.

First, community interpreter is placed in between the professional and the client having a different social status. Being in this social environment, he may show different kinds of professional behaviour motivated either by feelings towards the stranger (fear, contempt, compassion etc.) or towards the institution (agreement or disagreement):

- 1st aspect of the third – community interpreting requires that the interpreter makes an additional effort to overcome the limits of communication taking place within a more fragmented context due to the presence of several cultural[6] and linguistic entities;

- 2nd aspect of the third – community interpreting requires that the interpreter must try to encompass different, even antagonist and mutually exclusive voices if a conflict arises, by means of invoking human values (responsibility, compassion, common project…);

- 3rd aspect of the third – community interpreting includes a fact that the interpreter works on his own conscience.

The Role of Ethics in Community Interpreting

Plouhinec (2008, 38-39) points out that ethical and deontological references in community interpreting are significant in relation to the social and relational context underpinned by the implicit which may hinder the establishment of a dialogue between people of different cultures. He works with two presuppositions:

- the interpreter acts with the conviction that he can establish common ground despite the otherness and difference to enable the participants to enter in a relation of intercomprehension and find common solutions (besides that, the interpreter may have his own personal intentions, such as encouraging the participants to develop an attitude of openness);

- the interpreter bears in mind that the individual is not the reflection of a supposed culture of belonging, but he is unique, produced by his multiple affiliations and experiences – national, ethnic, social, and socio-cultural.

Based on the above-mentioned, the interpreter develops a methodology requiring a strong personal involvement. Nevertheless, in doing so, this attitude must be governed by two principles: neutrality and decentration.

According to Plouhinec (2008, 41), neutrality means that the interpreter develops understanding and empathy towards both participants. He must therefore refrain from choosing the one for which he develops an emphatic attitude and the other for whom he develops an analysing attitude, influenced by prejudice and judgments. The concept of decentration is defined by Carmel Camillieri as awareness and deconstruction of attitudes and other personality elements which prevent from accepting the other in his difference.

Fiola (2004, 124) speaks of ethics in community interpreting in relation to deontology, stressing out that both terms are closely linked. It’s based on a purely ethical reflexion that we can determine whether it is appropriate to interpret or to allow interpreting to happen, while deontology tries to define rules to be observed by interpreters (i.e. the way how to provide services while interpreting).

Therefore, Fiola (2004) further stresses out that ethics in community interpreting is guided by a willingness to do what the society considers just. It deals with the following questions: Under what circumstances is it good to interpret? Why interpret? Who for? or even How far does community interpreting go?

With regard to the last question, one of the questions we ask in the paper is: Where is the line between interpreter’s duty, prohibition, habit, strictness of the law, and human conduct?

Example 1 – Romanian Prisoner in Slovakia

The first example is taken from the interpreting experience in the Slovak prison context. Generally, interpreting for foreign prisoners is considered to be a very demanding task due to very stressful conditions. As pointed out by Müglová (2009, 140), during this consecutive transfer, the client is undergoing mental and/or emotional stress which may negatively impact the way he expresses himself (the speech is neither fluent nor logically coherent, he struggles to find correct words or uses slang and argotic expressions). Therefore, the interpreter has to not only be familiar with language varieties, but also ‘keep a cool head’ in order to handle the situation.

On top of this, as we present in this example, the interpreter may encounter a dilemma whether to keep helping the client, even if his task ended (with the translation of the judgment). In our example, the dilemma emerged after being asked to help with money transfer which would allow the prisoner to pay for some personal items.[7] His relatives couldn’t deposit money at the prison’s management nor give it to the prisoner in cash; the money had to be transferred to the bank account of the convicted person. Eventually, after receiving money from the Romanian relatives and after notifying the prison’s management, the interpreter kept sending money to the Romanian prisoner from his personal bank account. For instance, this procedure would not be possible in France and a sworn interpreter would exceed his powers by doing so. But again, the question that we are faced with is: Who sets the line between interpreter’s duty and a human conduct?

Interpreting for Detained Foreign Minors

The role of interpreters is even more complex when providing services to unaccompanied foreign minors. Balogh and Salaets (2015, 35) point out that beliefs regarding the recognition of the distinctiveness of childhood, children (under the age of 18) vulnerability (young age and lack of independence) represent the roots of the theory of children’s rights.

Children’s rights definitely play a major role in judicial proceedings and non-judicial/alternative proceedings. The example we provide is taken from the context of police interrogation of minor refugees and the related rights.

Example 2 – Moldavian Minors

In this example, we would like to present a case of two Moldavian minors detained by foreign police. From the standpoint of the translatology task, we also deal with consecutive transfer and the clients (minors) who are vulnerable may also be undergoing a lot of stress. The interpreter has to take all of this into account and adapt the way of communication with them. Besides that, the interpreter who passed the legal minimum exams and has necessary legal awareness must be well aware of the fact that he should not provide interpreting if a representative of the Social Affairs Department of the closest District Office or a United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)[8] representative is not present. In the protocol, the interpreter should state that he is providing services with this proviso, but neither the police nor the investigative body will include such a clause in the protocol since the protocol would be invalid in procedural terms. It is again one of the dilemmas the interpreter must face and decide what is the best attitude to adopt.

In all of the examples, we want to point out the diversity and variability of phenomena and unexpected situations interpreters have to deal with in community interpreting (and especially when interpreting for the minors).

Other Procedural Issues and Controversial Situations for Interpreters

Fusilier (2010, 22-23) states that sworn interpreters intervene most often in the judicial sphere. The missions entrusted to them correspond to the three phases of criminal proceedings: police investigation, instruction, and criminal hearing. During the investigation phase, the urgency of the procedure and the availability of the interpreter[9] not only to come immediately, but to stay as long as needed, are crucial. When this condition is not met, consequences can be very bad.

Example 3 – 71 migrants in a truck

This example falls within the scope of the third category of the already mentioned crisis situations defined by Müglová (2009, 200-201), more precisely, criminal activity of foreign nationals. In this type of consecutive transfer taking place in a very emotionally intense situation, the interpreter must often deal with the criminal’s effort to convince the police of their innocence in order to avoid imprisonment which may result in a very persuasive, even aggressive way of expression. The interpreter must therefore maintain his neutral and objective approach towards both parties.

However, in the last two years, we have been recording extremely tragic cases when the police didn’t find a suitable interpreter soon enough. As one press release stated: “On Thursday, a court in Kecskemét, Hungary sentenced to 25 years of imprisonment four persons who were accused of killing 71 migrants found in August 2015 in a refrigerated truck, parked near the Austrian town Parndorf. According to the first-instance judgement, an Afghan and three Bulgarians are guilty of complicity in multiple smuggling and homicide. None of the convicted shall be conditionally released from prison before he serves the 25-year sentence.“

We won’t go into details, but 71 migrants including women and children suffocated in a hermetically sealed refrigerated truck. The arrested Bulgarian driver and his Afghan accomplice originally left the truck after they discovered the cooling system wasn’t working. The police found the parked truck but didn’t open it. The driver and his accomplice were arrested the next day, however, they didn’t cooperate, and it took 24 hours for the police to find interpreters.

It may also happen that the interpreter is unpleasantly surprised with the investigative procedure itself.

Example 4 – Romania’s Romani Women

The 4th example describes a group of skinheads who brutally attacked Romania’s Romani women near the town of Trnava, Slovakia, just because they were selling fake gold at the parking lot. Based on the categorisation by Müglová (2009), we are dealing with the exact opposite of the previous example; the foreign nationals are victims of a criminal act. In this type of consecutive transfer, the emotions also play a crucial role and neutrality is needed from the interpreter. Based on what happen, the victims may feel oppressed, even discriminated because of their nationality.

In this regard, the interpreter was very intrigued by the investigator’s procedure. Firstly, the investigator called his superior and asked whether he can qualify the crime as a racially motivated attack. The superior was rather strict in this case and told him to qualify it only as a disorderly conduct. Qualifying it as a racially motivated attack would reflect in a bad way in the statistics and Slovakia would have a reputation of a xenophobic country. It is a clear example of raison d´être of the institute of uninfluenceable investigating judge in France.

Other unexpected situations for the interpreters can also occur in proceedings related to the adoption of a child, taking a child away (by the court), divorce, etc.

Challenges for the Future and Need for New Solutions

In following section, we will present some of the challenges that we deem important for the future of community and sworn interpreting. They can be built around three main axes:

- Growing need for other than English-speaking interpreters

Within the context of current migrant crisis, there is also an urgent need for interpreters whose working languages are other than English, and these are Arabic, Turkish, and Turkic. Interpreters speaking Arabic and Turkish are rare in Slovakia: they are either elderly or are students without any prior professional training.

Example 5 – Iraqi Christians in Nitra, Slovakia

We provide an excellent example of Iraqi Christians who received the right of asylum in Nitra (Western Slovakia) were interviewed by the police. In a group of 25 people, there was only one – a young woman (married, accompanied by her husband and their three children) – who spoke English. Her husband had to give his permission so that she could communicate with the Slovak interpreter in English.

- Intercultural aspects are on the agenda more than ever before

More specifically, we have in mind a perfect knowledge of culturally conditioned body language and gestures. For example, the raised hand of an American means STOP. However, an Arab perceives the raised hand as the sentence: “I come as a friend.” What happens if the gesture is misinterpreted is not hard to imagine.

Other cultural traditions: after hearing the view of European partners sitting opposite them, the Japanese remain silent for a long time. Many believe that they wait for the head of delegation or the oldest to speak. Even though the hierarchy and age principles are highly valued in Japan, this assumption is false. The Japanese are just thinking about what the European partners said to them.

Štefková (2006), one of the leading theoreticians and practitioners in the field of sworn and community interpreting in Slovakia, described a culturally conditioned gesture used in the adoption process by a Dutch couple. The adoptive parents showed sweets to a Romany boy, they gave them to him by using a gesture which in Dutch means ”Taste them. They’re good.” However, in our cultural background the same sign stands for beating and could be interpreted as ”Don’t dare to eat them”. As a result, the boy started to cry.

- Linguistic and psychological training of police officers (investigators involved in the asylum process) is also necessary.

From the viewpoint of linguistic training, the state administration presents several deficiencies. At the Slovak Academy of the Police Force, languages aren’t taught in a way which would enable police officers[10] to conduct interviews on their own in a foreign language (primarily the English language). Another issue is the basic infrastructure. It may happen that foreigners have to wait for an asylum interview even 48 hours. If solid material and technical equipment is missing, linguistic training of police officers can’t be one of the top priorities.

Conclusion

The paper reflects, above all, a new reality in the field of sworn and community interpreting. Considering the new globalization challenges, the status and role of sworn interpreters and translators are changing quite rapidly. Based on the gained interpreting experience, we stress that it is mainly the interpreter, not the investigator, who can positively influence procedural acts, and guide the affected or investigated person towards a meaningful cooperation.

When we talk about the irreplaceable role of a sworn interpreter, he often backs up the ex officio lawyer very successfully. However, we come to further procedural vacuum. The role of the ex officio lawyer ends by freeing or convicting the foreigner/migrant–perpetrator. But a convicted and imprisoned smuggler has other human rights and needs (making phone calls, buying food in a buffet if he/she doesn’t like the prison fare, buying cigarettes, etc., writing letters and hiring a translator). After the imprisonment, not only interpreters, but also translators play a crucial role. Determination and payment for translations of prisoner’s request and complaint form depends on the arbitrariness of prison or court management. If the court appoints an official translator, the entire process is usually too long, and certain terms can be time-barred, more precisely the substance of the prisoner’s request can be postponed. Not to mention translations of censored correspondence, etc.

The outlined issues of migration and new situations in which the sworn interpreter or translator may be involved require a new definition of his/her status at the international level by EULITA, but also in the Slovak Act No. 65/2018 Coll. Amending and Supplementing the Act No. 382/2004 Coll. on Experts, Interpreters and Translators and on Amendments and Supplements to Certain Acts, as amended. The continuing education of sworn translators and interpreters is also a necessity.

Educating and improving the quality of staff selection in the field of investigative forces is beyond our reach. Teaching new languages – especially Turkic languages (Turkish, Afghan, Persian, Kurdish, Pakistani) and selected African languages (Swahili, Hausa) – and preparation of relevant interpreters remains a permanent condition sine qua non. That’s where we see a potential room for coordination from the level of competent European Commissioners.

References

Balogh, Katalin and Salaets, Heidi. (ed.) 2015. Children and Justice: Overcoming Language Barriers. Cambridge, Antwerp, Portland: Intersentia.

Bakhtine, Mikhail. 1970. La Poétique de Dostoïevski. Traduit par : Isabelle Kolitcheff. Paris: Seuil.

Carr, Silvana et al. 1997. The Critical Link: Interpreters in the Community. Amsterdam; Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Fiola, Marco. 2004. Le « gain et le dommage » de l’interprétation en milieu social. In TTR : traduction, terminologie, rédaction, vol. 17, (no. 2), 115–130.

Fusilier, Evélyne. 2010. Traducteurs et interprètes experts : une exception française ? In Traduire, no. 223, 8-37.

Gentile, Adolfo and Ozolins, Uldis and Vasilakakos, Mary. 1996. Liaison Interpreting, A Handbook. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

Gile, Daniel. 2009. Interpreting Studies: A Critical View from Within. In Claramonte, Vidal and África, Carmen and Aixelá, Javier Franco (eds.), A Self-Critical Perspective of Translation Theories. Universidad de Alicante. MONTI Monografías de Traducción e Interpretación 1, 135-155.

Gromová, Edita and Müglová, Daniela. 2007. Preklad a kultúra 2 [Translation and Culture 2]. Nitra: FA CPU.

Grosu, Gabriel and Kopecký, Peter. 2016. Criza refugiaților sirieni sau reorganizarea priorităților securității Europei? [The Crisis of Syrian Refugees or the Re-Organisation of Europe’s Security?] In Transilvania Sibiu, vol. 7, 79-84.

Hrehovčík, Teodor. 2009. Teaching Community Interpreting: A New Challenge? In Ferečník, Milan and Horváth, Juraj (eds.). Language, literature and culture in a changing transatlantic world: International conference proceeding. 160-164.

Klimkiewicz, Aurélia. 2005. L’interprétation communautaire : un modèle de communication « trialogique ». In TTR : Traduction, terminologie, rédaction, vol. 18 (no.2), 209-224.

Mikkelson, Holly. 1996. Community interpreting: An emerging profession. In Interpreting, International journal of research and practice in interpreting, vol. 1(no. 1), 125-129.

Müglová, Daniela. 2009. Komunikácia, tlmočenie, preklad alebo Prečo spadla Babylonská veža? [Communication, Interpreting, Translation or Why Did the Tower of Babel Fall?]. Nitra: Enigma Publishing, s.r.o.

Opálková, Jarmila. 2016. Komunitné tlmočenie ako špecifický druh interkultúrnej komunikácie. [Community Interpreting as a Specific Type of Intercultural Communication]. In Jazyk a kultúra. [Language and Culture]. vol. 1 (no. 2).

Plouhinec, Asuman. 2008. L’éthique de l’interprète en milieu social. In Écarts d’identité, vol. II (no. 113), 38-41.

Roberts, Roda. 2002. Community interpreting: A profession in search of its identity. In Hung, Eva. (ed.). Teaching Translation and Interpreting 4: Building Bridges. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Štefková, Marketa and Motyková, Katarína. 2006. Kultúrne špecifické aspekty právneho štýlu v kontexte prekladu právnych textov z germánskych jazykov. [Culturally specific aspects of Legal Style in the Context of Legal Translation from Germanic Languages]. In Od textu k prekladu [From Text to Translation]. Prague: JTP. 99-104.

Internet resources

Critical Link International. 2018. Available at: https://criticallink.org/what-is-critical-link/. Accessed on 25 August 2018.

Eurostat statistics explained. 2019. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/images/f/f5/Number_of_%28non-EU%29_asylum_seekers_in_the_EU_and_EFTA_Member_States%2C_2017_and_2018_%28thousands_of_first_time_applicants%29_YB19.png. Accessed on 24 May 2019.

[1] Real numbers were even higher because thousands of refugees didn’t register and migrated secretly from one county to another.

[2]https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/images/f/f5/Number_of_%28non-EU%29_asylum_seekers_in_the_EU_and_EFTA_Member_States%2C_2017_and_2018_%28thousands_of_first_time_applicants%29_YB19.png

[3] For instance, in the Czech Republic, the Act on Experts and Interpreters does not differentiate between a translator and an interpreter.

[4] For the purpose of this article, the term “translatology task“ is used to refer primarily to interpreting.

[5] https://criticallink.org/what-is-critical-link/ (Accessed on 25 August 2018).

[6] Opálková (2010) claims that community interpreting without the knowledge of cultural background and ethnical mental stereotype of the migrant would be impossible.

[7] To clarify, in Slovakia, convicted prisoners must pay a part of costs related to their stay in prison (costs related to food and personal hygiene and for instance, fully cover the costs for cigarettes).

[8] However, in 2012, its office was moved from Bratislava to Budapest.

[9] It rarely happens that the investigated person refuses the presence of an interpreter claiming that he allegedly doesn’t speak English, but only the Hausa and Yoruba languages. That was the case of intestinal heroin transport by a Nigerian national (the case was blocked for several months).

[10] The situation in the medical field is different. This year’s bachelor theses, written by students of the Department of Translation Studies at the Constantine the Philosopher University in Nitra, Slovakia, showed that more than 50 % of Slovak doctors are able to communicate with foreign patients in English.