Claudia Förster Hegrenæs

Department of Professional and Intercultural Communication

NHH Norwegian School of Economics

Claudia.Hegrenaes@nhh.no

Ingrid Simonnæs

Department of Professional and Intercultural Communication

NHH Norwegian School of Economics

Ingrid.Simonnaes@nhh.no

Abstract

As an integral part of translator education, assessment has been addressed in many publications (e.g., Way 2008; Kelly 2014). In higher education in general, there has been a trend in recent years to move from summative to performative assessment. However, this has not yet been discussed to a large extent in the literature on translator education. The aim of this paper is to describe the transposition from an error-based (summative) to a criteria-based (performative) assessment system using rubrics at the National Translator Accreditation Exam (NTAE) in Norway. Due to a lack of training programs, the NTAE faces particular challenges when it comes to candidate qualifications and thus the assessment itself. We discuss the pros and cons of error-based and criteria-based translation quality assessment models, also regarding often-cited translation competence models and present a first draft of a criteria-based assessment model to be tested in the fall semester of 2019. We highlight the applicability of rubrics as both assessment tool as well as innovative teaching tool (e.g., providing feedback to support the learning process) not only for the NTAE, but for assessment in translator education in general.

Key words

Translation quality assessment, Translator education, Translator accreditation, Translation competence, Rubrics, Assessment for learning

1 Introduction

The aim of this paper is to discuss rubrics as an assessment and teaching methodology and respective didactic considerations in assessing translation products in the light of the absence of a regular teaching environment at the NTAE in Norway. The paper begins with some background information for the overall theme of this paper (section 2). Section 3 deals with rubrics in teaching, evaluation and assessment. The issue of translation quality assessment is discussed in section 4, including a short review of two important translation competence models and of relevant assessment models, before we in section 5 compare the old and new assessment model at the NTAE. The final section discusses the limitations of the new model as of June/July 2019 and outlines how we intend to continue working with the model.

2 Some facts about translator training in Norway

Norway offers considerably fewer translator education programs in comparison to continental Europe and the UK. At the University of Oslo different components geared towards translation are offered as part of language programs. At the University of Agder, a bachelor’s degree in translation and intercultural communication for Norwegian – English is offered. To become an accredited translator, Norway offers the NTAE1, for which NHH Norwegian School of Economics is responsible. Candidates have to account for at least 180 credits (the equivalent of three years of studies) from an institution of higher education. However, what they studied is irrelevant. It is here where our teaching methodology and evaluation/assessment model comes into play. First, however, we will describe the general characteristics of the NTAE.

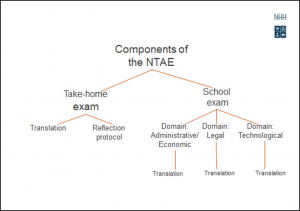

The NTAE is divided into two components: a take-home exam and a school exam (see Figure 1 below). At the take-home exam (fall semester) a general language text which covers a broad range of present-day topics is tested. In addition, the exam tests the candidates’ translation competence by way of a reflection protocol, where the candidates reflect on their translation products and processes. The translation and the reflection protocol are assessed separately, and both have to be passed. Every year there is a rather considerable number of candidates who do not pass the take-home exam.

The school exam (following spring semester) tests the competence in translating three different LSP-texts. The non-pass rate for the school exam is rather high as well. The relatively substantial number of candidates who do not pass the exam is the main reason why we want to change the assessment procedure by adapting our assessment model to also function as a feedback and learning tool.

Figure 1: Components of the NTAE

The new system intends to facilitate the candidates’ comprehension of the assessment criteria and to provide detailed evaluations of their translation performance according to these criteria. Furthermore, this evaluation can be utilized as feedback to the candidates, who can act accordingly (i.e., improve their performance). In the next section we describe the new performance-based system which consists of a criteria-based assessment model in the form of a rubric.

3 Using rubrics in teaching, evaluation and assessment 2

In teaching, evaluation, and assessment, rubrics have been used for several decades in educational systems around the world. In general, rubrics are defined as “a scoring tool for qualitative rating of authentic or complex student work. It includes criteria for rating important dimensions of performance, as well as standards of attainment for those criteria (Jonsson & Svingby 2007, 131). In other words, rubrics represent student performance expectations, as well as a means to qualitatively evaluate and assess this performance holistically.

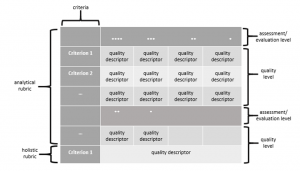

Rubrics consist of two main components, which are closely linked to its purpose: criteria and quality descriptors. Usually, rubrics are developed in the form of a matrix (see Figure 2 below). Criteria are specified in the left-hand column while quality descriptors are presented in the adjacent columns. The top row specifies the assessment or evaluation level, which can be expressed in multiple ways depending on the aim and use of the rubric (e.g., on a scale from A-F, or as quality denotations like Excellent, Good, Satisfactory, or Exceeds Expectations, Meets Expectations, Below Expectations). Quality descriptors may either be pre-formulated descriptions of student performance (analytical rubric) or individual free-hand comments (holistic rubric). The former categorizes student performance and, if developed carefully, enables especially teachers and examiners to proceed quickly through the evaluation or assessment process. In a holistic rubric the level of assessment or evaluation is not specified (e.g., free comments).

Figure 2: Theoretical model of a rubric

Rubrics can be used along two different dimensions: the level of education and the user group. Concerning the level of education, we will focus on higher education only. Firstly, rubrics are developed for use at three different levels of education. They can be designed for use at program level describing performance criteria and expectations of a specific study program at, for example, bachelor’s or master’s level. Furthermore, rubrics can be designed at subject or course level detailing performance criteria and expectations of the particular subject or course. Finally, rubrics can be designed for individual tasks and assignments within a course or subject describing in detail performance criteria and expectations. At task level, there may be several rubrics within one course depending on the number of tasks and the inherent characteristics of these assignments. If tasks are comparable aiming to achieve the same learning outcomes, rubrics may be developed to accommodate all tasks (i.e., they have transfer value). If, however, tasks differ from each other aiming at, for example, different learning outcomes, they have to be designed to accommodate each learning outcome individually, and the transfer value from one rubric to the next is rather limited.

Secondly, rubrics are developed to be used by different user groups: students, teachers, and examiners. Students use rubrics to familiarize themselves with assessment criteria and performance expectations as well as for self-evaluation. At the level of the individual task for example, students can evaluate their own performance in a given task against the criteria detailed in the rubric. This presupposes that rubrics are made available to the students with the task description. Self-evaluation supports students’ learning processes by enabling them to reflect critically on their own performance.

Teachers use rubrics to communicate performance criteria and expectations. In addition, rubrics constitute a tool for teachers to provide feedback on students’ performances (for a comprehensive discussion of feedback as a pedagogical tool to enhance students’ learning processes see Jonsson 2013), and to receive a general overview of student learning and learning progress. In other words, rubrics provide teachers with information on whether students are (on their way) to meet expected learning outcomes. If necessary, teaching can be adjusted to direct student learning accordingly.

Finally, examiners use rubrics to understand and apply the assessment criteria, which is especially important for example for external examiners who are not actively involved in the teaching. Rubrics have been discussed with regard to inter- and intra-rater reliability, and Jonsson and Svingby (2007) find that reliability can be approved given specific circumstances like training examiners in using the rubric or incorporating benchmarks into the rubric.

Since rubrics are used to assess the quality of student submissions, we believe that they are also applicable to the evaluation of translation products, to be described in the next sections.

4 Translation quality assessment in translator education settings

Research into professional translation competence assumes that translation “is a complex activity, involving expertise in a number of areas and skills” (Adab and Schäffner 2000, viii). There is, however, no general agreement on how this expertise is defined. Evaluating and assessing such expertise in translator education settings and accreditation is therefore rather challenging. Angelelli (2009) points out that translation quality assessment has to be based on a clear definition and operationalization of translation ability (i.e., competence) and that tests need to be designed carefully in order to ensure a reliable connection between the test itself and what the test is supposed to measure. Thus, quality assessment does not only entail “naming the ability, knowledge, or behavior that is being assessed but also involves breaking that knowledge, ability, or behavior into the elements that formulate a construct” (op. cit., 13; referring to Fulcher 2003). In other words, such tests need to measure translation competence.

4.1 Translation competence models

There are at least two translation competence models which are repeatedly referred to in the literature: the PACTE model and the TransComp model. Both models are relevant for our new assessment model to be presented in section 5. The PACTE model (PACTE 2003, 60; Albir 2017, 41) consists of the following sub-competences: bilingual, extralinguistic, instrumental, knowledge of translation and strategic sub-competence, where the strategic sub-competence is placed in the middle of the model, surrounded by the other sub-competences. All sub-competences interact with psycho-physiological components, for example, memory, perception, intellectual curiosity, perseverance and creativity and logical reasoning. Göpferich’s TransComp model (2009/2013), building upon the PACTE 2003-model, consists of communicative competence in at least 2 languages (cf. PACTE’s bilingual sub-competence), domain competence (cf. PACTE’s extralinguistic sub-competence), tools and research competence (cf. PACTE’s instrumental sub-competence), translation routine activation competence (cf. PACTE’s knowledge of translation sub-competence), psycho-motor competence (no direct comparable sub-competence in PACTE) and again, placed in the middle of the model, the strategic competence interacting with all kinds of the listed competences.

In the following section, we describe existing translation quality assessment models which are relevant for our decision to change the current assessment model.

4.2 Review of relevant assessment models in translator education settings

The majority of existing translation quality assessment systems is designed with particular focus on error identification and quantification. Similar approaches have been presented and introduced either fully or partly, for example, in the US system (American Translators Association ATA), the Finnish system and the Australian system.

Colina (2008; 2009) suggests a functional-componential approach as a result of her analysis of current translation quality assessment methods. These methods have, as she argues, not achieved middle ground between theory and applicability (Colina 2009, 239). Further, she rightly argues that translation quality is a “multifaceted reality” which should be reflected in an assessment model where multiple components of quality should be addressed simultaneously (ibid.). Colina’s quality assessment tool (TQA) evaluates components of quality separately, therefore called a functional-componential approach. The advantages of this approach are that the user/the requester of the translation decides which aspects of quality are more important for the communicative purposes (Colina 2009, 240). The quality is not assessed on the basis of a point deduction but rather on suggested descriptors for each component.

Turner et al. (2010) present a comparison of two methods of translation assessment, i.e. error analysis/deduction vs. use of descriptors. They compare international testing bodies that have moved/are moving towards using descriptors or combining negative marking and descriptors. They find a high degree of correlation between the Australian National Accreditation Authority for Translators and Interpreters (NAATI) and the UK Diploma in Public Service Interpreting (DSPI) 3 assessment models which leads them to conclude that NAATI “might be able to move towards a descriptor-based system without sacrificing reliability of assessment” (Turner et al. 2010, 13f.). The advantage of a descriptor-based system is that descriptors offer more holistic assessment than the NAATI error analysis/deduction system. The observation by Turner et al. that international testing bodies are moving towards using descriptors is a valid argument for the NTAE to adopt a similar assessment model.

Phelan (2017) looks at analytical assessment of legal translation using the ATA framework. This case study is especially interesting because legal translation is considered the most challenging text type of the three LSP-texts tested at the NTAE (see Figure 1). The ATA uses a negative marking system where the threshold for pass is predefined as a concrete number of points. This analytical approach should allow for a “more objective, replicable system based on the identification of errors” (Phelan 2017, 1). However, the author acknowledges that this approach still contains some subjectivity with regard to the examiner’s decision on the seriousness of the error (transfer errors) where (s)he can impose either 1, 2, 4, 8 or 16 points.

From this short review, we conclude that adopting a descriptor-based assessment system seems reasonable, especially when we consider the possibility to apply the model also in a learning situation for the candidates at the NTAE, which is described in the next section.

5 Old and new assessment model at NHH

As described previously, the Norwegian system of higher education does not offer sufficient educational programs which lead directly to the NTAE. Repeatedly, candidates seem to rely on their proficiency in the relevant language combinations, but this language competence is only one of the sub-competences (see section 4.1 on translation competence models) as well as only one of the criteria tested in the NTAE. Angelelli (2009) points to the inherent relationship between the understanding or definition of translation competence that underlies a test, in this case a certification exam, and the test itself (op. cit., 30 f.). Angelelli argues that, for example, the American certification exam focuses on a componential definition of translation competence, but in practice “the tendency is to focus more on the grammatical and textual competences” (op. cit., 31), which is realized in an analysis and quantification of error types. Therefore, “[w]hen operationalizing the construct, professional associations tend to have a narrower definition of translation competence, and many times pragmatic and other elements are not included in the construct to be measured” (ibid.). Thus, Angelelli refers to what she perceives as a gap between research on translation competence and testing of the same construct by accreditation authorities.

Due to the lack of translation-specific training, most of the candidates of the NTAE represent a special group of testees in such a context. Due to the nature of the exam (accreditation) and the sometimes non-professional and varied translation qualifications of the candidates, the exam focuses on translation features which represent sub-competences that candidates can be expected to possess without or with limited prior translation training/education and experience. Therefore, our old approach to assessment has been largely based on error type identification focusing on i.a. textual translation and grammatical features, and not, as proposed by Angelelli on an “operational construct […] articulated along similar lines to those used in translation studies in order to capture translation in its entirety and thus properly measure it” (Angelelli 2009, 31, emphasis added).

Wherever possible, attempts have been made to follow current research in the field regarding exam situations. For example, in order to make the exam situation as comparable as possible to a real-life working situation, a translation brief (assignment) accompanies each translation task in the exam, detailing the origin of the source text, the purpose of the target text and the target audience. This change was introduced in 2013 and follows a functionalist approach (Nord 1997). Göpferich (2009) also references the translation assignment in her model. Since 2016 internet access is granted during the school exam. The exploitation of online resources of various kinds is an integral part of the work of professional translators, and is, for example, captured by the tools and research competence in Göpferich’s TransComp model (2009; 2013) or the instrumental sub-competence in the PACTE model (2003; Albir 2017, 40).

As mentioned above, our old assessment model is based on an error analysis where the errors are categorized according to their severity, in either major or minor errors with subcategories:

1) Major errors that may lead to non-pass:

• Disregard of the translation brief

• Misinterpretation of the message of the source text

• Omission of whole clauses/sentences – including omission of the use of brackets for omissions made in the source text, marked as «[…]» or omission of significant units in sentences

• Use of wrong concepts/terminological errors

• Serious violations of genre conventions

• Uncritical use of resources

2) Minor errors that may lead to non-pass

• Alternative translation suggestions

• Less serious violations of genre conventions

• Errors in the general vocabulary (not influencing the meaning of the text message)

• Unidiomatic language use and style

• Morphological and syntactical errors

• Misspellings and wrong punctuation

• Repetitive careless mistakes

When used repetitively, this category may lead to “non-pass”. Errors in this category reflect the candidates’ missing language competence, especially in the target language. Major and minor error categories test most of the above-mentioned sub-competences in the PACTE and TransComp models. To sum up, even if we do not assign any number of points to the subcategories (threshold), the central question is how few/many errors are acceptable in order for the translation to still be assessed as “pass”. Our experience has shown that we seldom see a candidate whose translation only contains one major error, such as misinterpretation or omission of a whole sentence/paragraph. Thus, most often it is likely to find more than just one major error. In addition, usually translations contain also minor errors.

Candidates are informed of the result of the assessment (summative, pass/non-pass) after the exam period is over. Candidates are always entitled to request an explanation according to the Act Relating to Universities and University Colleges, Section 5-3. The value of explanations (until now as comments on error types and respective examples) as formative feedback has been underestimated both on our behalf and on behalf of the candidates 4. Candidates may receive valuable information in order to produce a translation which conforms to the required level of translation quality/competence in future exams. Candidates who have passed the take-home exam and thus advance to the school exam, can and should utilize the explanations to prepare for this final part of the exam. They can focus on improving potential weaknesses (e.g., violations of text type conventions, morphological and syntactical errors), which helps them to develop their translation competence and to be better prepared for the school exam. The value of feedback to support the learning process has been discussed in section 3.

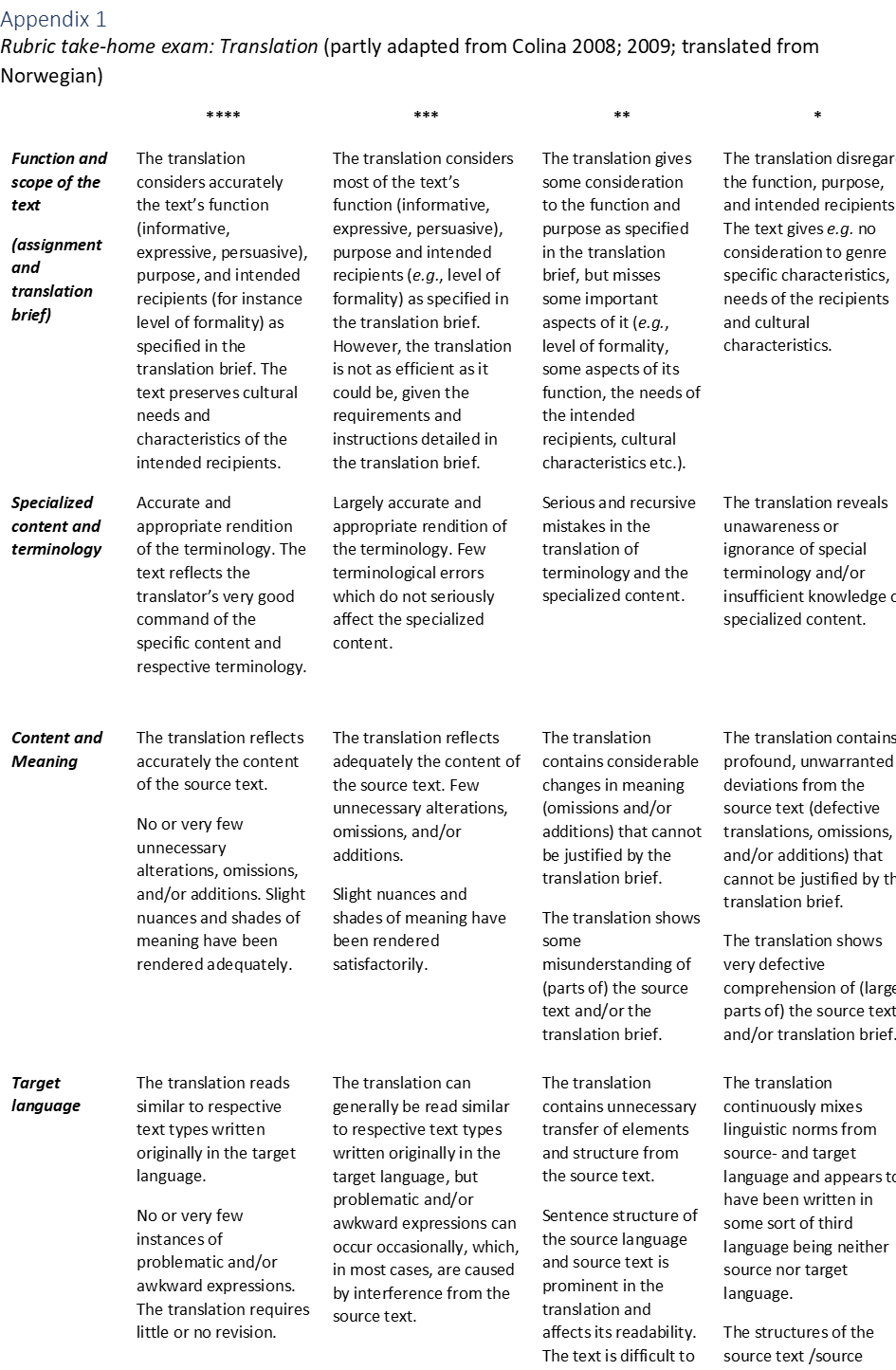

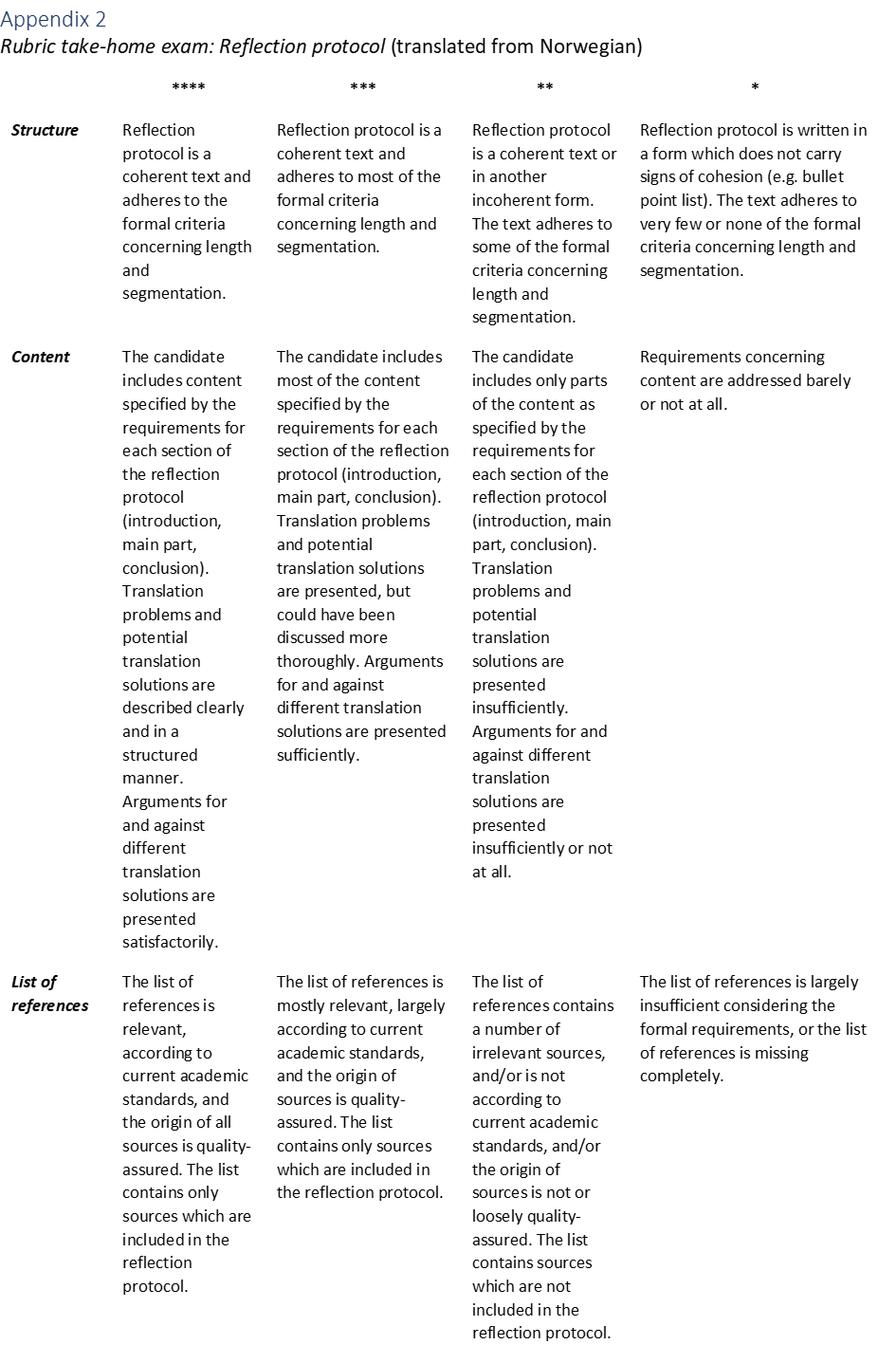

In order to refine the error criteria used at the NTAE, and to utilize the value of feedback that lies in the identification and categorization of these error criteria in exam papers, the steering board has recently decided to move towards an evaluation/assessment matrix, which is based on a descriptor system, in line with the ones described by Colina (2009) 5 and Angelelli (2009). The error criteria system as described above represented the starting point for the rubrics that have been developed to be implemented in the NTAE 2020 (fall 2019, spring 2020). In other words, the criteria tested during the exam remain the same. and aim to capture the different translation sub-competences (see section 4.1.). Two analytical rubrics were created representing the two parts which are object of assessment of the take-home exam: a translation and a reflection protocol (see Figure 1). As such, the rubrics are specifically designed for an individual task or assignment, which is our exam. For the translation rubric, five assessment criteria were established: Function and scope of the text (assignment and translation brief), Specialized content and terminology, Content and meaning, Target language, and Grammar and spelling. The five criteria are partly based on Colina’s suggestion of a functional approach to translation quality assessment (2008; 2009).

Function and scope of the text (assignment and translation brief) refers to the transfer and placement of the translated text into the target language and culture according to the translation brief. It considers the function of the text (informative, expressive, appellative) and the hypothetical target audience. Specialized content and terminology cover the rendition and use of specialized terminology related to the specific text type. Content and meaning relates to the appropriate transfer of meaning-making content from source to target text. This criterion covers translation phenomena like additions, omissions and alterations, which have an impact on the quality of the translated text in terms of target audience comprehension. Target language refers to the identification and classification of the target text as part of a larger class of target language texts which are originally produced in the target language. In other words, unless otherwise specified by the translation brief, candidates are expected to apply a translation strategy which results in the target text being comparable to texts produced in the target language. Finally, Grammar and Spelling measures the candidates’ performances according to grammatical correctness in the target language. This criterion differs from the previous criterion in that it evaluates concrete, measurable phenomena which are determined by the target language grammatical rules and norms.

For the reflection protocol rubric, the following five assessment criteria were established. Structure, Content, List of references, Reflection ability, and Grammar and Spelling. The reflection protocol is to be written in the target language. Thus, the criterion Grammar and Spelling evaluates candidates’ performance in that target language once more (in addition to the translation itself). Structure refers to purely formal features of the text pertaining to layout and composition: The text is to be written in essay form consisting of three main components: an Introduction, a Main part, and a Conclusion, which are to be clearly marked by division into sections and subsections. The required length is 1,500 to 2,000 words. The Content needs to reflect the three structural parts of the reflection protocol. The introductory part presents the source text and the translation brief and reflections on the relationship between the two considering its implications on the translated text. The main part considers challenges and problems related to specific topics like terminology and cultural references, and the conclusion summarizes the principal reflections of the main part. The criterion List of references addresses the use of relevant sources like dictionaries, termbanks, and other printed and online resources, which need to be presented adhering to an established academic standard (e.g., APA, Harvard). Reflection ability considers the candidates’ ability to consciously identify and critically discuss their translation and the process that led to the translated text. Finally, Grammar and Spelling measures the candidates’ performance according to grammatical correctness in the target language. After having presented the assessment criteria included in both rubrics, we will now briefly describe the corresponding assessment and quality levels.

Each assessment level is divided into four sublevels. Each sublevel is marked by a number of symbols (stars) starting with four symbols indicating the best performance to be expected by a candidate and ending with one symbol indicating non-compliance with the majority of the components of a criterion. For each criterion, quality descriptors were defined for each assessment sublevel. To define these quality descriptors, the following resources were considered: Colina (2008; 2009), The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment (CEFR), and the experience of internal examiners, who have been developing and assessing the NTAE for a considerable number of years. This way, four quality descriptors of expected translation performance, ranging from best to lowest, for each of the five assessment criteria in both rubrics were devised (see Appendix 1 & 2). As such, the rubrics are intended to be used by the examiners (user group) of the exam as grading guidelines as well as to decide upon the final grade (pass, non-pass).

The rubric for the translated text has been tested informally by three examiners (French, German, Spanish) during the assessment of the school exam in the spring of 2019. The rubric for the reflection protocol could not be tested since the discussion of the new assessment system only started after the take-home exam in the fall 2018. The internal examiners were asked to fill out the rubric alongside their assessment of the translations and evaluate whether the criteria and qualitative performance descriptors are comprehensible and applicable to the translations they were assessing. Their feedback has not yet been analyzed at length, but initial comments indicate that the rubric was applicable and useful for assessment. They merely suggest minor changes in wording clarifying the content of specific quality descriptors and/or delimiting quality descriptors more clearly from each other. These changes will be evaluated and addressed before the rubrics are introduced into the NTAE 2020.

Concerning the utilization of the rubrics for learning and feedback, that is for the candidates, the rubrics will be employed in two ways: Firstly, as a tool to communicate assessment criteria before and during the exam period, and secondly as a tool to provide valuable feedback to candidates on their performance. As a tool to communicate assessment criteria, the rubrics will be published on the exam website clearly communicating the assessment criteria and performance expectations. Candidates will be encouraged to actively use the rubrics when working on their translations and reflection protocols, for example by self-assessing their work against the criteria and quality descriptors in the rubrics before submitting. In addition, the rubrics will be published together with the exam in the school’s digital exam and assessment platform WISEflow, which is used to conduct the exam. Examiners will electronically fill out the rubrics in WISEflow during the assessment process. This rubric assessment can be automatically released to the candidates together with the exam results. Marked quality descriptors indicate how a candidate’s performance has been evaluated related to a specific criterion. If necessary, candidates can easily extract from the rubric what needs to be done in order to improve performance 6. Here, the steering board faces two choices: whether to release rubric feedback to all candidates of the take-home exam, or only to the candidates who pass the take-home exam. The latter will be implemented as a means of helping those candidates to prepare for the school exam by identifying potential problem areas and prepare accordingly. This way, we hope to provide a means to further candidates’ learning processes even without exposing them to any form of translation teaching and training, and thus to increase the number of candidates who eventually pass the complete exam and become accredited translators. However, whether rubric feedback will also be released to candidates who do not pass the take-home exam, is dependent on administrative considerations like workload and time use. Specifically considering that it is rather unsure whether or when these candidates will attempt to take the exam anew.

6 Limitations and implications

The aim of this paper was to describe the transposition from an error-based to a criteria-based assessment system at the NTAE in Norway. Due to the insufficient number of training programs, the NTAE faces particular challenges when it comes to candidate qualifications as well as the assessment itself. In order to meet these challenges, the new performance-based assessment model (rubrics) will be used from the fall semester of 2019. As of now, the model has only been tested internally, and not in the exam itself. Therefore, neither examiners nor candidates are familiar with the new model yet. Both user groups have to be thoroughly acquainted with the model before the exam. In applying the model, we will detect problem areas (e.g., too strict quality descriptors) and adapt accordingly. On the other hand, the multiple application possibilities of the model, both as assessment and learning and feedback tool, are promising with regard to the specific situation in Norway, but also with regard to translator education in general. Our assessment model builds on the research by, for example, Colina (2008; 2009) and Angelelli (2009) and develops further a performance-based approach to assessment in higher education within translator education. However, we have not yet employed the rubrics in the exam, and can therefore, at this point in time, not draw any validated conclusions.

References

Adab, B. J., and Schäffner, C. 2000. Developing translation competence. Amsterdam: J.

Benjamins.

Albir, A. H. (ed.). 2017. Researching Translation Competence by PACTE Group.

Amsterdam/Philadelphia: J. Benjamins.

American Translator Association (ATA). Certification. http://www.atanet.org/certification/.

Accessed on: 30 June 2019.

Angelelli, C. V. 2009. Using a rubric to assess translation ability. In: Angelelli, C. V., and

Jacobson, H. E. (eds.). Testing and Assessment in Translation and Interpreting Studies. A call for dialogue between research and practice. Amsterdam: J. Benjamins, 13-47.

Colina, S. 2008. Translation Quality Evaluation. Empirical Evidence for a Functionalist

Approach. In: The Translator, 14(1), 97-134.

Colina, S. 2009. Further evidence for a functionalist approach to translation quality

evaluation. In: Target. International Journal of Translation Studies, 21(2), 235-364.

Fulcher, G. 2003. Testing Second Language Speakers. London: Pierson Longman Press.

Gardner, J. 2012. Assessment and learning (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

Göpferich, S. 2009. Towards a model of translation competence and its acquisition: the

longitudinal study TransComp. In: Göpferich, S., Jakobsen, A. L., & Mees , I. M. (eds). Behind the Mind: Methods, Models and Results in Translation Process Research. Frederiksberg: Samfundslitteratur, 11-37.

Göpferich, S. 2013. Translation competence. Explaining development and stagnation from a

dynamic systems perspective. In: Target. International Journal of Translation Studies, 25(1), 61-76.

IoL Educational Trust (ed.) (2017). Diploma in Translation – Handbook for Candidates.

http://www.ciol.org.uk/sites/default/files/Handbook-DipTrans.pdf . Accessed on 13 June 2019.

Jonsson, A. 2013. Facilitating productive use of feedback in higher education. In: Active Learning

in Higher Education, 14(1), 63-76.

Jonsson, A., and Svingby, G. 2007. The Use of Scoring Rubrics: Reliability, Validity and

Educational Consequences. In: Educational Research Review, 2(2), 130-144.

Kelly, D. 2014. A handbook for translator trainers: a guide to reflective practice.

Oxfordshire/New York: Routledge.

Kivilehto, M., and Salmi, L. 2016. Evaluating translator competence: The functionality of the

evaluation criteria in the Finnish examination for authorized translators – Handout presented at the Conference TransLaw 2016, Tampere, 2-3 May 2016.

Nord, C. 1997. Translating as a Purposeful Activity. Functionalist Approaches Explained.

Manchester: St. Jerome.

PACTE. 2003. Building a translation competence model. In: Alves, F. (ed.). Triangulating

Translation: Perspectives in process-oriented research. Amsterdam: J. Benjamins.

43-66.

Phelan, M. 2017. Analytical assessment of legal translation: a case study using the

American Translators Association framework. In: The Journal of Specialized Translation (27), 189-210.

Salmi, L., and Kivilehto, M. (2018). Translation quality assessment: Proposals for developing the

Authorised Translator’s Examination in Finland. In: Liitmatainen, A., Nurmi, A., Kivilehto, M., Salmi,L., Viljanmaa, A., and Wallace, M. (eds). Legal Translation and Court Interpreting: Ethical Values, Quality, Competence Training. Berlin: Frank & Timme, 179-197.

Turner, B., Lai, M., and Huang, N. 2010. Error deduction and descriptors – A comparison of two

methods of translation test assessment. In: T&I The International Journal for Translation and Interpreting Research, 2 (1), 11-23.

Vigier, F., Klein, P. and Festinger, N. 2015. Certified Translators in Europe and in the Americas:

Accreditation Practices and Challenges. In: Borja Albi, A. and Prieto Ramos, F. (eds). Legal Translation in Context. Professional Issues and Prospects, Oxford etc.: Lang, 27-51.

Way, C. 2008. Systematic assessment of translator competence: In search of

Achilles’Heel. In: Kearns, J. (ed.), Translator and Interpreter Training. Issues, Methods and Debates. New York/London: Continuum International Publishing Group. 88-103.

- A comparison of different accreditation practices in other European countries can be found in Vigier, Klein & Festinger (2015).

- We distinguish here between evaluation and assessment. Evaluation does not trigger marking/grading, but is rather meant to, for example, provide feedback to students on learning processes or provide the teacher with a snapshot of student learning status/progression. Assessment on the other hand is meant to set a mark/grade on student performance on different scales (e.g., pass/non-pass, A-F etc.).

- For more details on the DPSI and Diploma in Translation, see DipTrans Handbook 2017, https://www.ciol.org.uk/DipTrans. Accessed on: 14 June 2019

- For a comprehensive discussion of assessment for learning see John Gardner (2012).

- For discussion of similar criteria see e.g. Turner et al. (2010); Kivilehto & Salmi (2016) and Salmi & Kivilehto (2018) with further references there; and DipTrans Handbook 2017.

- A candidate is allowed to sit for the exam three times.