Mehmet Sahin

Abstract

In an initial effort of identifying the needs and expectations in translation technologies in Turkey, there are many questions to be answered about the profile and views of the major actors in the field of translation and interpreting: (1) students, (2) faculty members, and (3) professional translators and interpreters. This study tried to portray current situation in the country through documentary research and three surveys. The analyses of answers to the survey questions, websites of universities and translation companies, bibliography of research on translation technologies in Turkey suggest that in spite of the increasing interest in the field, translation technology is underrepresented in the curricula, research, and the translation market. Through careful curricular revision, with more faculty members specializing in and researching about technology, and with more support and opportunities of in-service training for practicing translators; a satisfactory level of progress can be expected for translation technologies for Turkish language.

Keywords: translation technologies, translator training, pedagogical issues, computer-assisted translation, machine translation, Turkish language

1. Introduction

The Anatolian and Mesopotamian regions, where, currently, the majority part of the Republic of Turkey is established, have always been a meeting point of different cultures and languages, as various nations conquered, resided in, passed by, or departed from these regions. In today’s world, Turkey is still embracing different languages and cultures, with Turkish as the sole official language of the country. The country’s relations with institutions and organizations such as the European Union, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the United Nations, and many other regional ones, have significantly increased the need for foreign language speakers mainly for the languages such as English, French, German, and recently Russian and Chinese among many other less commonly taught languages. This need paved the way for the establishment of translation and interpreting departments in higher education institutions. The first universities to offer a translation and interpreting (T&I) degree for the English-Turkish language pair were Boğaziçi University and Hacettepe University in the 1983-1984 academic year, just three years before Turkey submitted her application for accession to the European Economic Community. They were followed by Yıldız Technical University (French-Turkish) and Istanbul University (German-Turkish), and Bilkent University (English-Turkish-French) in the early 1990’s (Eruz 2003). As of the start of the new millennium, we witness a mushrooming of T&I departments in universities, particularly in non-profit foundation universities.

Interestingly, the same time period is also marked by the developments in translation technologies1 in the world. New tools and software were released and adopted quickly in the translation market. Translation memories, terminology management systems, and machine translation systems took their place in the field. Numerous research studies were conducted about these tools, presenting positive evidence for their contribution to the translation process. It can be argued that the growth of T&I departments in number has not had similar repercussions in computer-assisted translation (CAT) tools and machine translation (MT) development and research in Turkey. For example, MT systems for English-Turkish– the most commonly used language pair – seem to be still in their inception. Although MT systems for languages such as English and Russian have a past for more than half a century, only by the new millennium, we have started witnessing comprehensive MT studies for the English-Turkish pair. However, the earliest project for English-Turkish machine translation, in fact, goes back to early 60’s. But the project “never found its way to an actual computer” (Troike 2011, 469). Within the framework of the Georgetown University Machine Translation (GUMT) Project, Ross MacDonald visited Turkey to conduct some work on the comparative syntax of English and Turkish, and during 1961 there was “some discussion about setting up a pilot project for English-Turkish translation” (Macdonald 1963 cited in Troike 2011, 469). There were several discussions of potential of using computers in the translation process (e.g. Sezer 1991) among Turkish educators, but in practice, traditional methods have been persistent till the end of the millennium.

The translation field in Turkey has three major actors apart from the clients: translation faculty members, translation students and translation professionals. In the last decade, there have been several studies investigating the role, importance, and future of CAT tools and MT in translation studies and practice in Turkey (Öner 2006; Şahin 2009; Canım 2011 and Canım-Alkan 2013; Ersoy and Balkul 2012; Şahin 2014; Şahin 2015, etc.) from different perspectives. However, there has been no study investigating and cross-referencing the view of the said three parties. The current study aims at presenting the status quo in the translation field in terms of technology use, with a special focus on the needs, requirements, expectations, and concerns from the perspectives of students, academicians, and professionals.

Translation Technologies in Turkey

Translation technologies in Turkey have a decade-long history. Between the years 2005 and 2006, we witness an article of computer-aided translation, (Büyükaslan n.d.) establishment of a translation memory company (Set Soft Bilişim Teknolojileri Yazılım ve Donanım Sanayi ve Ticaret Anonim Şirketi – founded 15 February 2006), and an article on localization (Öner 2006). A three-year scientific project on statistical machine translation (SMT) between English and Turkish was conducted between 2005 and 2008 (Oflazer and Durgar-El Kahlout 2008). Google Translate added Turkish to its services in 2009. Hutchins [CITATION Joh09 \n \t \l 1055 ], in his comprehensive list of MT systems for all languages in the world, lists eight MT systems for English into Turkish: Çevirmen, Translator/Çevirim, Language Weaver, LEC, Sametran, Transclick, TranSphere, WebTrans (116) and 5 systems for Turkish into English: Language Weaver, LEC, Transclick, TranSphere, WebTrans (123). Among the online MT services listed by Hutchins [CITATION Joh09 \n \t \l 1055 ], only few of them support English-Turkish language pair: Babelfish, Babylon-Pro, Dictionary.com Translator, Google Translate, LEC Translate DotNet, Windows Live Translator [currently Bing Translator], and Worldlingo. There are also some recent products such as Omnifluent Translate (App Tek n.d.), which offers hybrid machine translation (HMT) services for Turkish language.

Research on CAT and MT, though, goes back a decade further, to late 1990s, mainly conducted by computer engineers with minimal, if any, involvement of translation faculty members (Hakkani, et al. 1998). The field of translation technologies has started to attract the attention of translation scholars in the world and consequently in Turkey in the recent years due to several factors. The first reason can be the changing nature of the translation profession with more complicated translation tasks requiring translators to have more technological competence such as using desktop publishing (DTP) tools. The second reason is obviously the new demands and practices in the field such as localization, post-editing MT output, web translation, fansubbing, and crowdsourced translation. As these new demands and practices emerged, translation educators remarked the need to investigate the dynamics behind and integrate it into their teaching and research. The third reason is of course the changing profile of the learners, which are usually called “digital natives” (Prensky 2001). The new generation of learners often deem the use of traditional methods of teaching and translating boring, unproductive and demotivating. The first course book on computer-aided translation was published in early 2000s by Lynne Bowker (2002). Turkish readers had to wait 11 years to read a similar book ( Şahin 2013b). Research studies on translation memories (Canım 2011), the Internet use (Şahin 2014), post-editing (Şahin 2013d), web translation, technology in translator training (Gümüş 2013 and Gümüş 2014) virtual worlds (Şahin 2013a) proved that the interest in translation technologies has grown in the last ten years in the context of Turkey as well. However, in a year where the volume of studies and developments in the world reached a level of saturation insofar as to be reflected in an encyclopedia of translation technology (Chan 2015), one can argue that the same cannot be said for the case of Turkish language. Moreover, despite the imbalance in regard to variety and quality of CAT tools and MT and to volume of studies between commonly taught and spoken languages and Turkish, the volume of translations is growing each day and turn-around time for translation tasks is becoming less and less for both in a parallel manner.

The place of translation technologies in the curriculum in Turkey has also been subject of several studies. Despite the abundance of undergraduate programs in T&I, it is interesting to see that there is no consistency among universities in regard to the weight that technology should have in the process of educating translators (Şahin 2013c). Balkul (2015) investigated this issue in detail through collecting data from university web sites and surveys from 72 translation educators in Turkey. Balkul (2015) identified 15 public universities with 28 T&I departments in various languages and 14 private universities with 20 T&I departments in various languages based on official data available in 2014. The study also provides valuable insight about the views of the faculty members of T&I departments on the use and teaching of CAT tools. Almost all academicians stated that CAT tools should be taught in T&I departments and about half of them preferred that such a course should be compulsory whereas the second half stated it can be elective or both. In the same study, the researcher found that about 85% of faculty members did not have any training on CAT tools. Gümüş (2013) investigated the curricula of two universities and stakeholders in the translation market in her doctoral thesis and found that technology competence is essential in the translation market and yet translators complained about the lack of training in technology. In her survey to 89 translation graduates of two universities, Gümüş (2013, 143), found that “translation technology (51.2%), translation history (39.8%), knowledge of linguistics (36.4%), professional work procedures and professional ethics (35.2%) and communication skills in A language (34.1%) are the components that, according to the respondents, were rarely or not dealt with in the translation program.”.

On the other hand, there seems to be a clear message from the EMT (European Master’s in Translation) project that technological competence is a crucial part of translation competence. Also, except for one failed attempt, there is no single graduate program in translation technologies in Turkey, whereas we witness a growing tendency of graduate studies in the field of localization, machine translation or computer-aided translation in Europe and elsewhere. It is evident that we need to take serious steps to reach a consensus on the place of technology in T&I studies and practice in Turkey. To this end, it is essential to explore the profile and views of three major actors in the field of translation and interpreting across the nation: translation students, faculty members, and translation professionals. The current study aims at answering the following questions:

-

What are the profiles of the translation students, faculty members of the T&I departments, and translation professionals?

-

What do the faculty members of the T&I departments, translation professionals, and translation students think about the present and future status of translation technologies in the academia and in the market?

-

What do translation scholars/educators and translation professionals think should be done in order to promote translation technologies for Turkish language?

2. Methodology

The data were collected through electronic surveys through Google Forms designed for three different groups in a five month period, between January and June 2015. A total of 271 people participated in the study. The informed consent form was automatically received as participants agreed to proceed to the survey after reading the description of the research study.

The following means were used to reach the participants:

-

students enrolled in the researcher’s institution through personal contact

-

students enrolled in other institutions through e-mails, posts on online boards

-

university web sites for the contact information of the faculty members of T&I departments

-

social media

-

translation and interpreting associations

-

web sites of the translation companies

-

personal connections

-

snowballing

The participation in the survey was voluntary. Almost all participants were confirmed to be real persons as most of them provided their personal information although it was not a required item. The participants seemed to be interested in the topic of the study: despite the fact that the survey was quite long (approximate time of completion was about 20 minutes), 75% of translation professionals and 83% of faculty members agreed to be contacted again if any such need emerges. The surveys included Likert-scale, open-ended, checkbox-type and ordering questions, some of which were optional. The data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics with SPSS 17.0 and Microsoft Excel 2013.

As seen in Table 1, the overall turnout of the surveys suggests that the study has the potential of reflecting the general situation in the country.

Table 1

Participants of the study

|

Participants |

Number of participants |

Number of questions in the survey |

Profile of the participants |

Estimated total number in Turkey |

|

Undergraduate students |

125 |

60 questions |

from 8 different universities (3 public, 5 private) 21 freshman 22 sophomore 41 junior 41 senior |

1500-2000 (not confirmed) |

|

Faculty members (survey sent to about 200 faculty members nationwide) |

65 |

80 questions |

40 work in public universities 25 in private universities 21 graduate assistants 20 lecturers (16 MA, 3 PhD) 14 assistant professors 5 associate professors 6 full professors 13 taught courses on translation technologies 12 have only undergraduate degree 24 have MA degree 29 have PhD |

150-200 (not confirmed) |

|

Translation professionals |

81 |

80 questions |

Primary role: 59 – translation and interpreting 13 – management 5 – technical support / proofreading 4 – training 18 self-employed 26 freelance 18 work in translation offices 14 work in private institutions 5 work in public institutions |

Unknown |

However, it can be argued that the study should be replicated in different contexts, cities, or institutions in order to reflect potential similarities or differences. It should also be noted that the number of professional and non-professional translators and interpreters is currently unknown and that the data from current study would never be final. However, considering the similar curricula, similar technological background and infrastructure and similar market dynamics; the inferences from the current data can be taken as an indicator of the current situation in the country as a whole.

3. Results and Discussion

Any discussion about the place of technology in translation education and practice would involve the current profile of the parties involved in both: translation students, faculty members of T&I departments, and translation professionals. The surveys designed within the framework of the current study included 10 to 20 questions about the background and habits of the participants about technology.

Participants’ profile and general views

The use of a computer for the first time in one’s life can be an indicator of the willingness to use technology or of the learning or working style. 85 students (68%) used a computer for the first time before the age of 11 and only 6 students (about 5%) after the age of 15. On the other hand, only 6 faculty members (about 10%) used a computer before the age of 11 and 48 (75%) after the age of 15. These percentages seemed to level off for translation professionals: 20 professionals (25%) used a computer before the age of 11 and 34 (about 43%) after the age of 15.

Students use social media extensively, about 63% use it for more than two hours a day. Only about 23% of the faculty members, and about 30% of translation professionals use social media for more than two hours a day. About half of the translators use social media, e-mail groups, portals, and discussion forums for professional purposes; whereas only 20% have a professional website or blog. More than half of all participants declared themselves to be multitaskers; one fourth (for all three groups) even went further to state that they can work on three different tasks at the same time.

28 students (30%) never took a course on computer technologies, and 29 (23%) students never took a course on translation technologies – 11 of these students have already finished their first year in their studies. Excluding those students, the rate goes down to about 15%. However, if we look at the market, we witness a very low rate: Almost three fourth of the professionals (72.5%) never took a course on translation technologies.

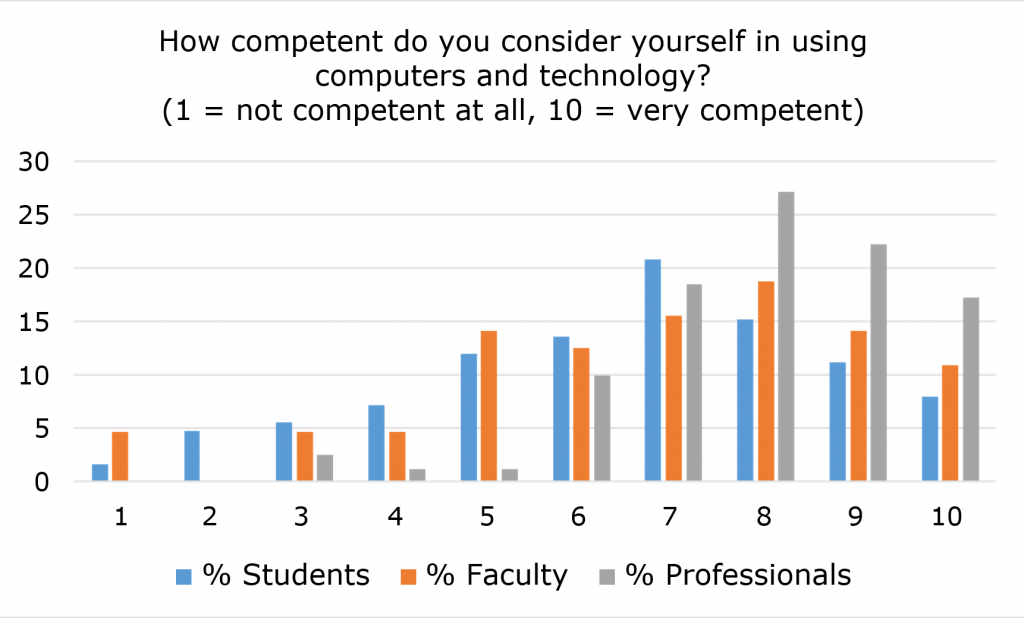

All participants declared themselves to be competent in using computers and technology, translation professionals being the most competent and faculty members the least with 41% of the participants under the level of 7 (See Chart 1). Again, almost all participants use technology in their daily life very often, except for about 15 percent of translation students and faculty members who use technology to a moderate extent. One-way ANOVA tests showed that there was a statistically significant difference between groups (See Table 2). Post hoc analyses were conducted using Tukey’s post-hoc test and the difference between professionals and faculty members, and between professionals and students was significant (p < .01).

Table 2

One-Way Analysis of Variance of Technology Competence by Participant Groups

|

Source |

df |

SS |

MS |

F |

p |

|

Between Groups |

2 |

117.38 |

58.69 |

13.728 |

.000 |

|

Within Groups |

267 |

1141.52 |

4.275 |

||

|

Total |

269 |

1258.90 |

There was no statistically significant difference between students across years (p < .01) or between faculty members across titles or age groups (p < .01), yet the mean value for professors was the lowest (M = 4.66/10). Moderate negative correlation was observed between age groups and competence levels among faculty members (r = 0.65, p < .05).

Chart 1. Self-perceived competence in using computers and technology

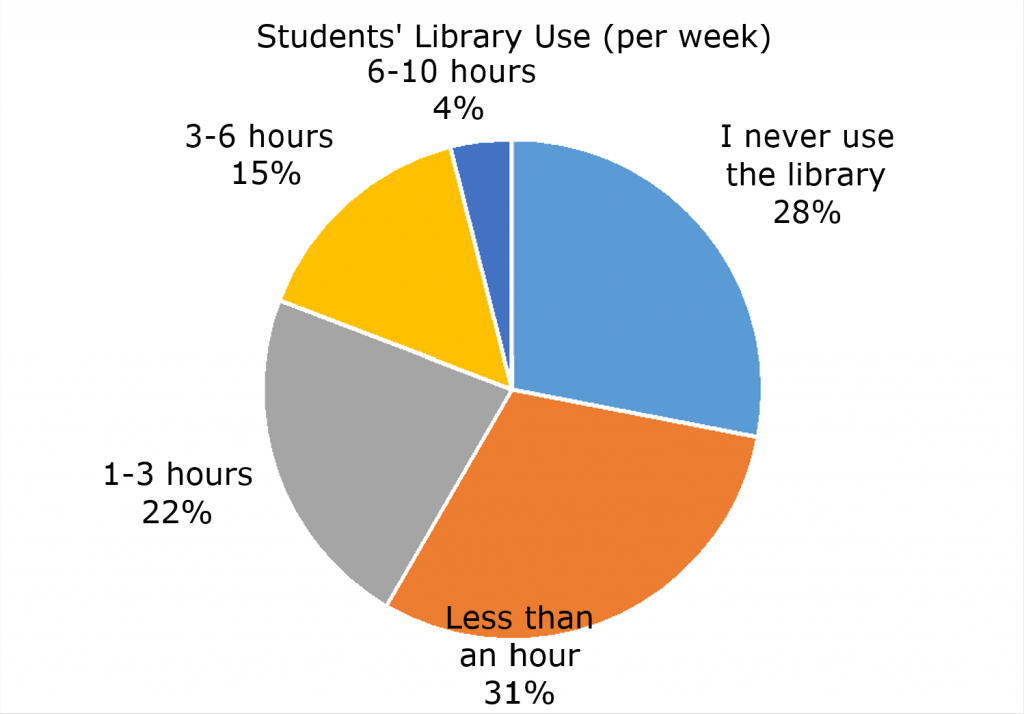

An interesting finding of the study was about the students’ library use. About one fourth of the students never use the library and half of the students use it less than three hours per week (See Chart 2). This finding suggests that most students prefer using the Internet to reach information and corroborates the argument that the new generation of students are more likely to use electronic resources rather than printed ones, which is also proven by the results of the survey in the current study. Answers to the survey questions also indicate that translation students use the Internet, word processing programs, and their smart phones in their translation tasks very often.

Chart 2. Students’ library use

42 faculty members out of 65 provided information about their latest academic degree major. 16 of them had their latest degree in T&I studies and 10 in linguistics. Other degrees are in languages and cultures (N = 6), education (N = 5). However, it should be noted that these degrees are the latest ones; some of the faculty members may have their earlier degrees in T&I studies. The faculty members are teaching lessons in English-, French-, and German-Turkish translation programs. About 40% of the faculty members teach interpreting courses as well. Upon a brief examination of the websites of T&I departments and research studies conducted in by their faculty members, only a couple of scholars list translation technologies in their research interests and the number of studies on this topic, as well as of studies using technology in T&I research is quite low.

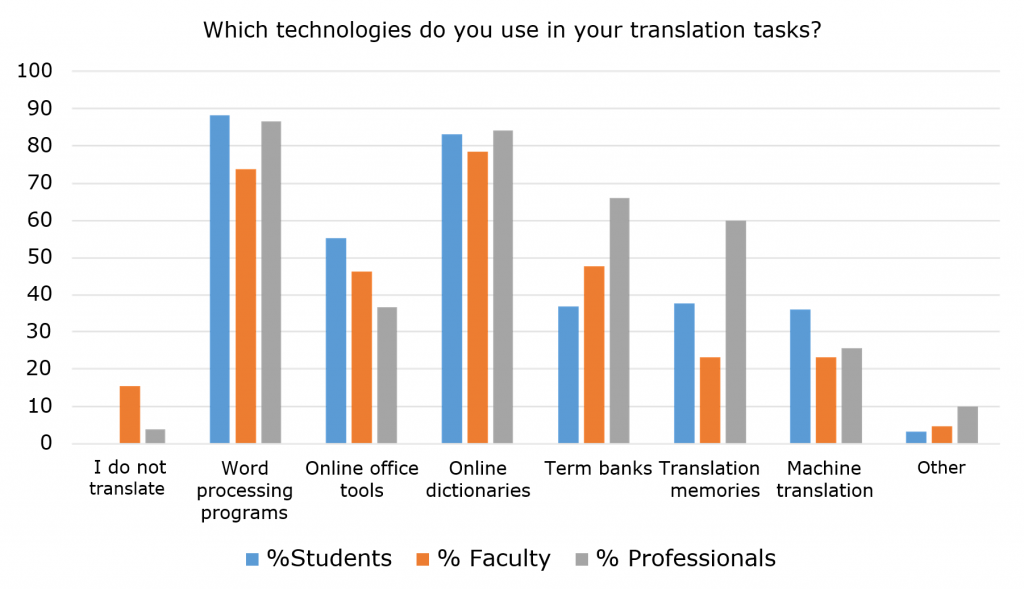

43 out of 80 professionals have their undergraduate degree in T&I studies, 15 in various fields related to language studies and 26 in other unrelated fields such as economy, chemistry, management, mathematics, philosophy, and so forth. Only three participants work only with literary texts, whereas others translate texts from various fields such as law, economics, politics, science, etc. All participants were asked about the technologies they use in their translation tasks. Translation students and translation professionals seem to be more engaged in using technologies (See Chart 3).

Chart 3. Technologies used by the participants in translation tasks

Practice of and attitude towards MT and post-editing

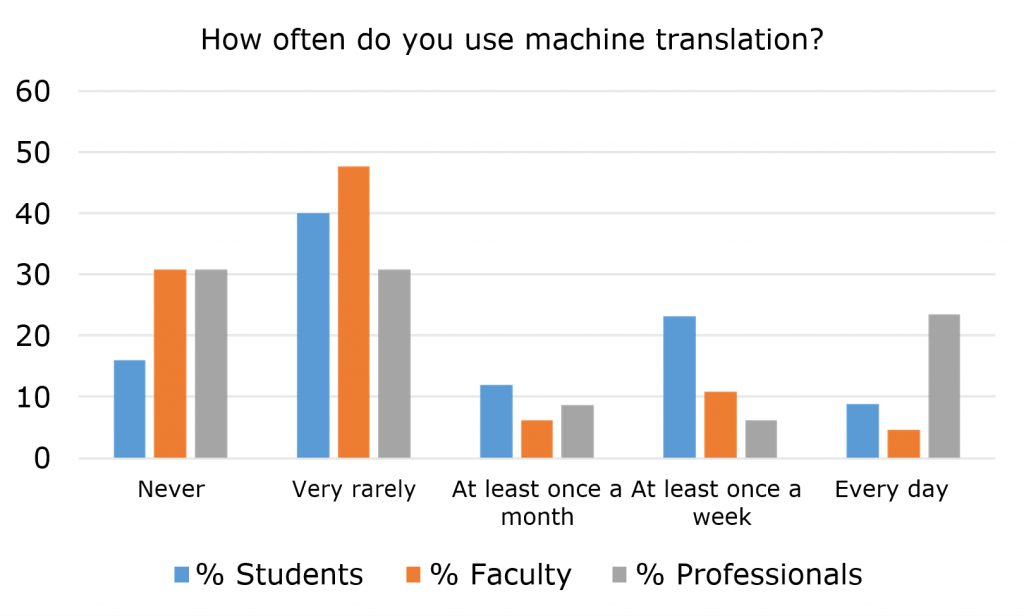

It is of great importance to see the general attitude of the main actors in the field of translation and interpreting towards MT and post-editing in any attempt to speculate about the current trends and to provide insights for the future. Participants seemed to have different habits of MT use. More than half of all participants either never used MT or used it very rarely. Faculty members used it the least. About one fourth of the translation professionals used MT every day (See Chart 4). The most popular MT service was Google Translate for all three groups.

The participants consider MT systems for English-Turkish unsuccessful in general. 17% of faculty members did not have any idea on this topic, probably since they never tested it. Translation students and faculty members seem to have more confidence on MT. They believe that MT can contribute to the translation process (70% and 75.4% respectively), whereas only 42% of professionals shared this view.

76% of students, 78.4% of faculty members and 56.8% of professionals believe that MT will improve to a considerable extent in the near future. About 16% of all groups were undecided. Developments in MT were perceived as a risk for the future of the translation profession more by the students (M = 3.01/5) than faculty members (M = 2.15/5) (p < .01). Translation faculty members were more optimistic than translation professionals about the idea that fully-automatic high-quality machine translation (FAHQMT) would be possible by the end of this century.

Chart 4. MT use by the participants

Participants were also asked whether translators should contribute to the betterment of MT systems by post-editing MT output. A one-way ANOVA revealed a significant difference between groups (p < .01) (See Table 3). The difference between the faculty members and professionals was significant according to the results of Tukey’s post-hoc analysis. Almost 75% of faculty members believe that translators should improve MT systems through PE, whereas less than half of the professionals support this view.

Table 3

One-way Analysis of Variance of Contribution to MT Betterment by Participant Groups

|

Source |

df |

SS |

MS |

F |

p |

|

Between Groups |

2 |

26.44 |

13.22 |

7.86 |

.000 |

|

Within Groups |

268 |

450.71 |

1.68 |

||

|

Total |

270 |

477.16 |

Senior students had more post-editing (PE) experience than freshman students (p < .01), but overall PE experience was below average for all students. Upon investigation of syllabi of translation technology courses or translation courses in general, post-editing has never been a component of any course in Turkey, except for one experimental course by Şahin (2013d), where students post-edited Google Translate output from English into Turkish. In Şahin’s (2013d) study, students’ negative attitude toward MT and post-editing had lessened by the end of the experiment. In the current study, more than half of the professionals believed that translating from scratch would be an easier task than post-editing MT output. About 35% of the students and faculty members did not agree with this statement and about 30% of both groups were undecided. Post-hoc analyses were conducted using Tukey’s post-hoc test. There was a statistically significant difference between professionals and students, and professionals and faculty members (p < .01). Only about 40% of the translation faculty members and professionals believed that having a translation degree is necessary for the PE tasks, a view that was shared by 64% of the translation students. Experience in the translation profession was seen as an asset for PE tasks. Special training for PE was foreseen by only 21% of the professionals and about 28% of the faculty members.

On the other hand, only about 47% of the professionals believed that MT can save time, whereas about 65% and 75% of translations students and faculty members respectively reported such belief. The idea that long and boring texts should be translated by machines so that translators can focus on more interesting and creative tasks was supported only about one fourth of all the participants. The difference between faculty members and professionals in regard to MT integration in the translation process was statistically significant for four genres: technical, legal, financial, and medical texts (p < .01). Faculty members seemed to be more optimistic about the MT output for those texts than professionals did. Both groups agreed that MT should not be integrated into translation process for literary texts.

Translation faculty members and professionals agree that there is not enough number of studies to develop Turkish MT systems. More interdisciplinary research studies are desired by both faculty members and professionals. However, about 71% of the faculty members stated that institutional support for studies in the field of translation and interpreting is insufficient. One striking finding was that although about 80% faculty members stated that they would like to be part of projects to develop MT systems for Turkish language, this percentage was only 50 for professionals and another 21% were undecided on this issue.

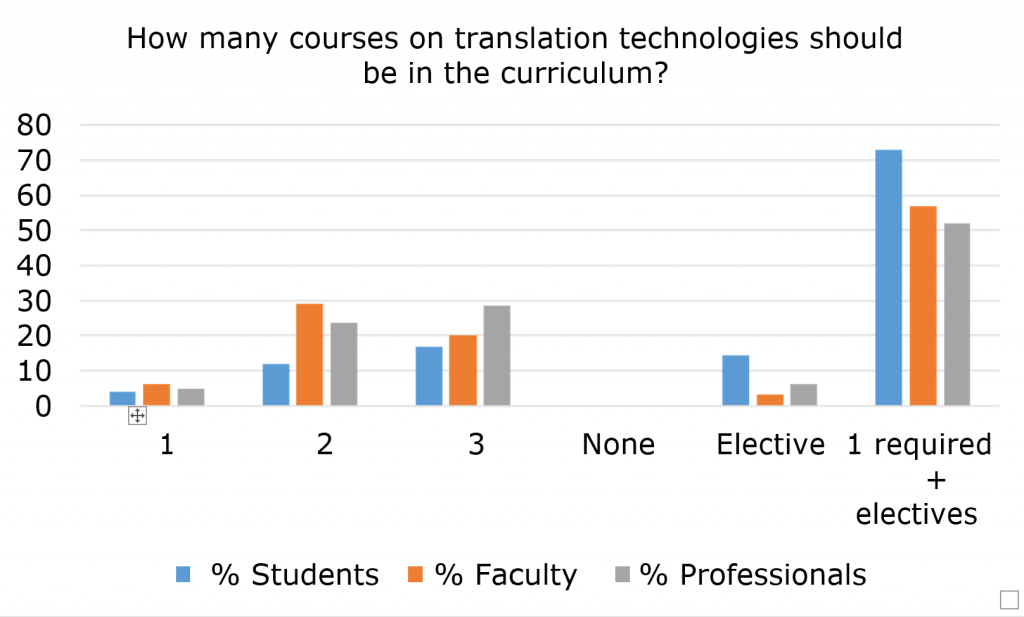

Course on translation technologies

T&I departments in Turkish universities offer different number of courses on translation technologies and in different semesters. There is not any common policy as to when in a four-year program such a course should be offered, whether it should be compulsory or elective, and whether students should have the opportunity to take advanced courses as electives or even as a requirement of their degree (Şahin 2013c; Balkul 2015). In the current study, participants stated that there should be at least one course on translation technologies and advanced courses should be taken as an elective course. About 15% of the students (N = 18) would like such a course as an elective, whereas only two faculty members and five professionals share this view. About 30% of translation faculty members and one fourth of professionals opt for two courses in the curriculum. About 30% of the translation professionals even voted for three courses in a four-year program. All participants consider such a course essential, except for one student and one professional; a couple of participants were undecided (See Chart 5). In their additional comments, most of the students who took a course on translation technologies in their second or third year in their undergraduate program stated that they would like to have the course in their very first year so that they can use their knowledge and skills in other translation classes.

Chart 5. The number of courses in translation curriculum

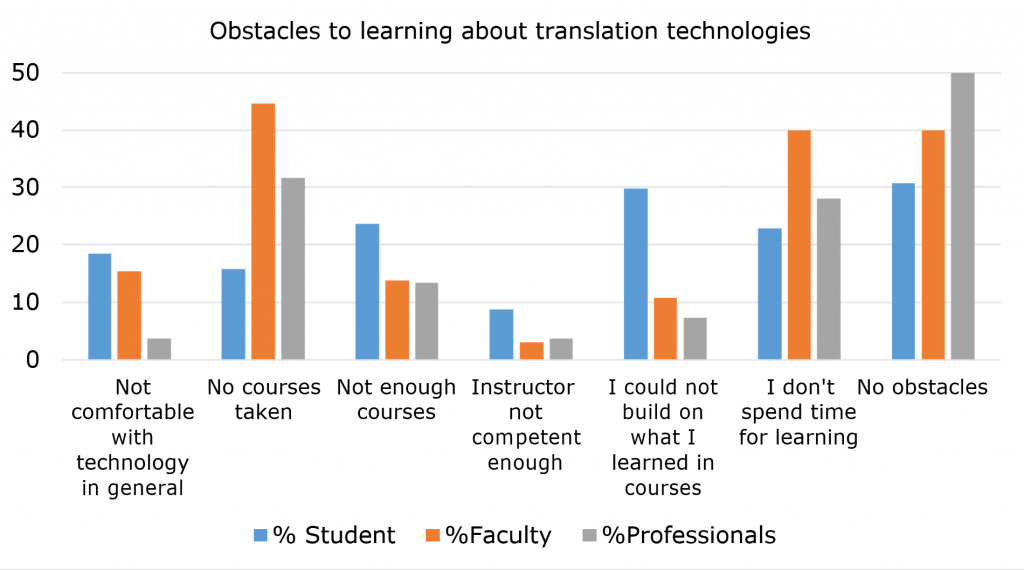

Obstacles to learning about translation technologies

It is essential to know what impedes translation students, faculty members, and translation professionals from learning about translation technologies in order to be able take necessary measures to reverse the status quo. Analysis of the surveys showed that 29 students did not take any course on translation technologies and only 11 of those were in their freshman year. Those 11 students were excluded from the analysis for this question. Although most of the participants reported not having any obstacles, lack of training or courses and failure to allocate time for this purpose seem to be the most common reasons. Moreover, some translation students do not seem to be eager to improve themselves by building on what they learn in classes. About 15% of translation professionals stated that they have not seen any need to use translation technologies so far in their career. About 8% of faculty members do not think that learning about translation technologies would contribute to their academic success (See Chart 6).

Chart 6. Obstacles to learning about translation technologies

Translation market

Each year hundreds of students graduate with a degree in translation and interpreting and seek jobs in the market and T&I departments have the responsibility to prepare their students well-equipped for the market needs. In the current study, a series of questions were asked about the technology use by translation professionals, views of faculty members and translation professionals about the needs and requirements in that sense. First of all, the results revealed that more than 90% of the translation professionals agree on the necessity of coordination between translation departments and translation market to be able to act according to the market needs.

Translation professionals agree that technological competence is a required component in the market. More than 60% of all participants agreed that translators should be knowledgeable about translation technologies not only in practice but also in theory. No statistically significant difference was observed across groups. Almost all of the participants agree that translators should be able to use the following tools and technologies efficiently: office programs (word processing, spreadsheet, and presentation), term banks, TM systems, terminology management systems, localization programs, desktop publishing programs, optical character recognition programs, speech technologies, MT systems, web design tools, and sound and video editing programs.

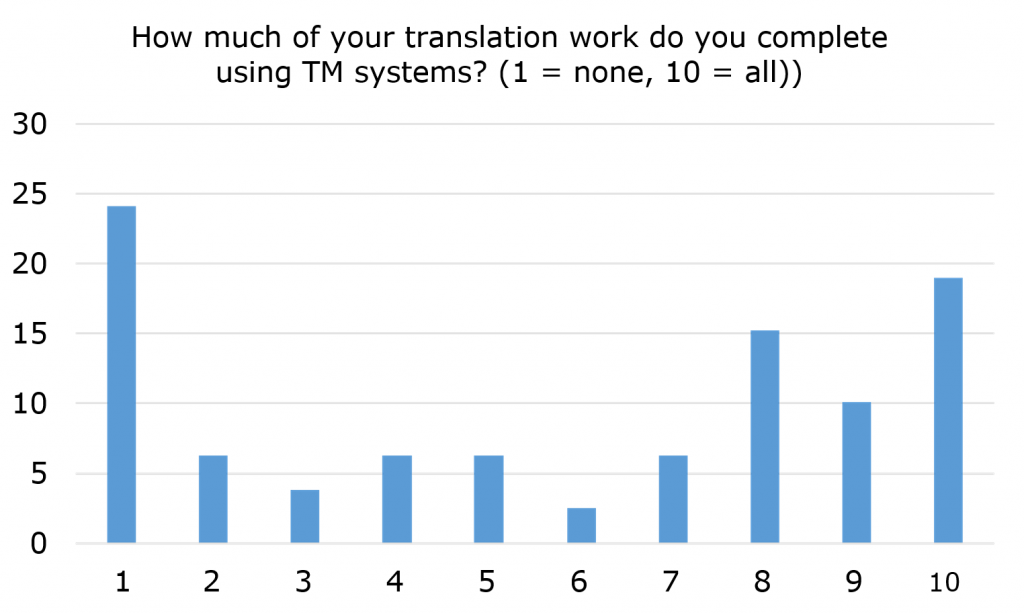

The importance of having technological skills and competence in the employment process was investigated through a question directed to translation professionals with administrative powers. Out of 13, one did not answer the question and 11 out of 12 participants stated that they give importance to technological competence of job seekers. About 75% of professionals translators stated that their knowledge of and competence in using translation technologies facilitates their work. They use TM systems for some of their work and about one fourth of the translators do not use TM at all (see Chart 7). The most popular TM systems among translation professionals are SDL Trados (58.8%), Google Translator Toolkit (25%), and MemoQ (21.3%). 12 professionals do not use any TM systems. OmegaT, an open-source TM system, is used by only 10 translation professionals.

Chart 7. TM use by translation professionals

About 14% of professionals disagree with the statement that being competent in translation technologies is a requirement for translators in order to survive in the translation market. One fourth of translation students, and around 15% of both faculty members and professionals were neutral about this statement. More than 70 percent of students and professionals, and more than 80 percent of faculty members agreed. There was no statistically significant difference between the three groups.

About one fourth of the faculty members do not consider themselves informed about the functioning, requirements and dynamics of the translation market. About 20% of the translation professionals stated the same. Half of the faculty members consider themselves informed to a moderate extent.

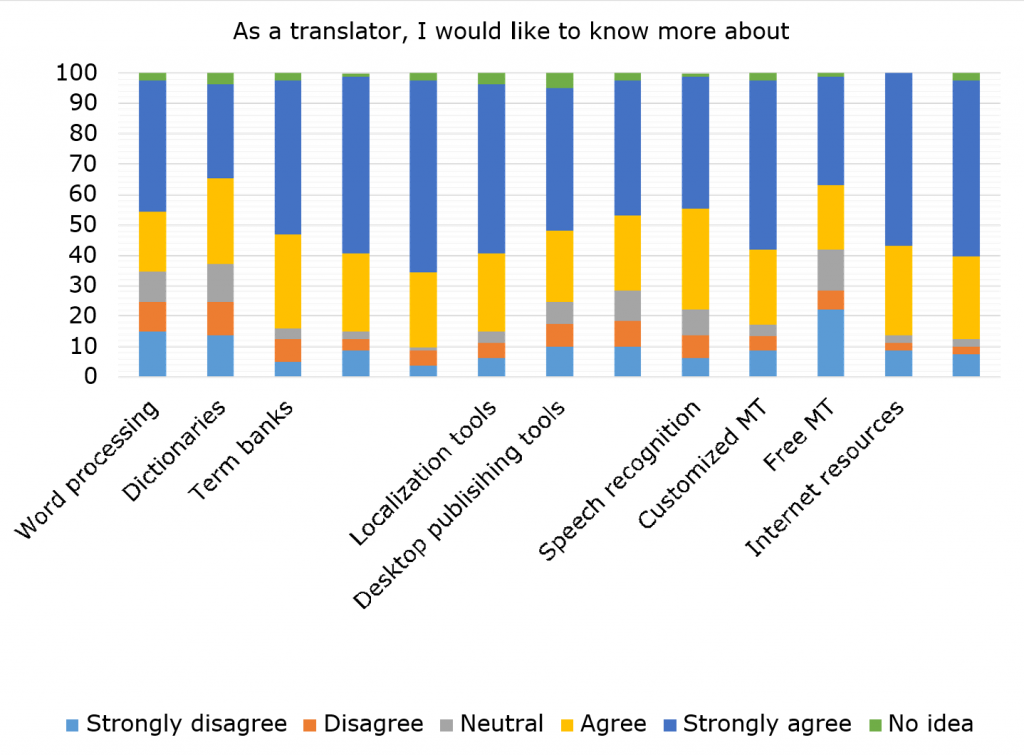

Support for professional development for translators

The answers of 35 translation professionals who work at a private or public institution, translation office suggest that there is not enough support from the employer’s part in terms of increasing technological competence of the translators. Two of the translators stated that there is no such need. On the other hand, almost all of these translators declared their desire to participate in certificate programs or in-service training sessions on translation technologies (M = 4.57, SD = 0.88). When all participants considered (N = 78, three participants did not answer the question), the same tendency is observed (M = 4.21, SD = 1.20).

Participants were asked about the areas and tools that they would like to know more about. The answers by the three groups were similar to each other. The views of the translation professionals can be seen in Chart 8. The areas highlighted with dark blue and yellow colors indicate that except for free MT and online dictionaries, translation professionals are interested in learning more about technologies involved in translation work.

Chart 8. Areas of self-improvement for translators

Benefits and drawbacks of using translation technologies

All three groups were asked about the benefits of translation technologies for translators and drawbacks of using such technologies. More than 90% of all participants agreed that time saving is a benefit. Half of the students and professionals believed that translation technologies increase quality but only 32% of faculty members shared this view. Faculty members also had a different view about the fact that using translation technologies is healthier and that it reduces costs.

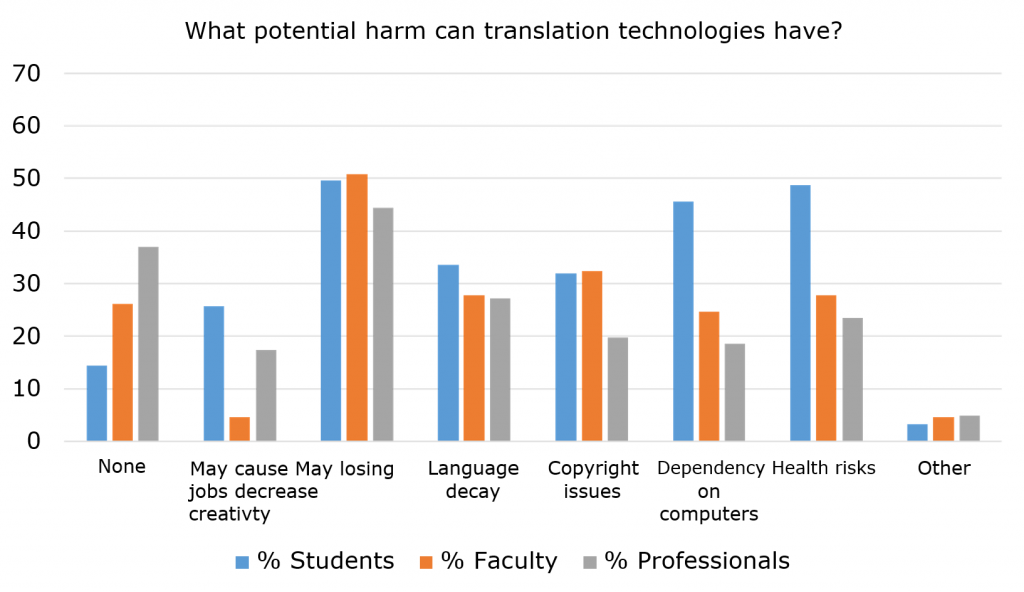

There were striking differences between the participants in regard to possible harms that translation technologies could bring. Faculty members did not seem to consider translation technologies as a threat to translators’ jobs, whereas one fourth of students and about one fifth of translation professionals thought so. Students also seemed to be more concerned about dependency on computers and health risks that working on computers could engender. About half of all participants believed that technology may decrease creativity and about one third were concerned about language decay (See Chart 9).

Chart 9. Potential harms of translation technologies

Translation students were asked on which topic they would like to work if they pursued graduate studies in the field of translation and interpreting. The most preferred topics were: audio-visual translation (30.4%), interpreting studies (29.6%), localization (25.6%), literary translation (24%), cultural studies (18.4%), computer-aided translation (16%), medical translation (8.8%), and machine translation (7.2%). The faculty members were also asked the same question in a different way: if you were to complete a second graduate degree in T&I, which topic would you focus on? CAT, localization, and MT were quite popular topics with rates 29.2%, 18.5% and 10.8% respectively. Translation professionals, on the other hand, had somewhat different preferences in terms of specialization: 36.6% in literary translation, 26.8% in localization, 18.3% in cultural studies, 17.1% in legal translation, and 15.9 in CAT. Machine translation received the least attention (3.7%).

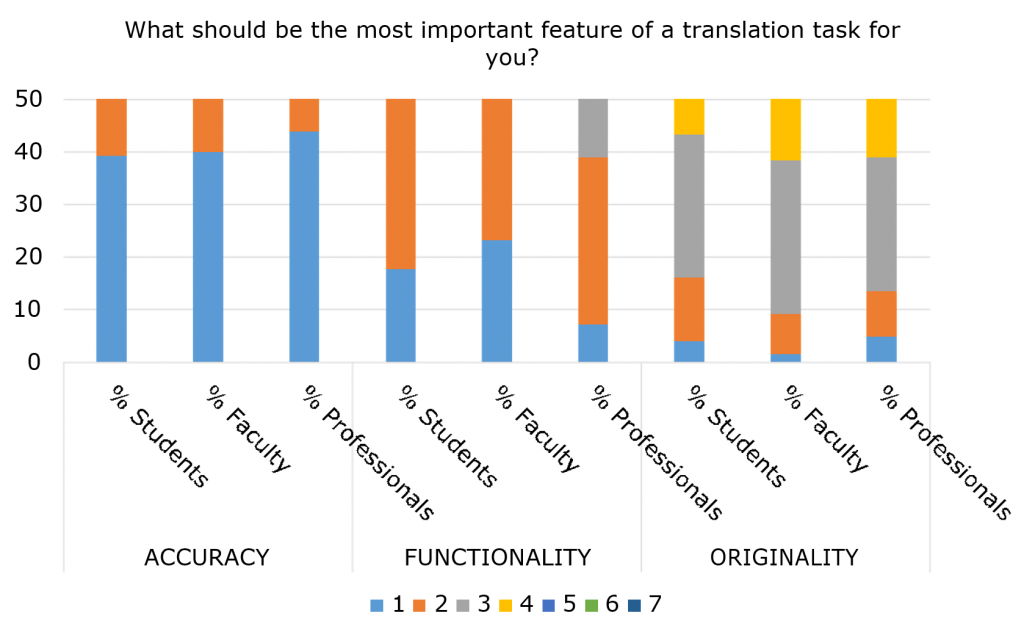

Priorities in a translation task

All groups were asked about their priorities in a translation task: accuracy, functionality, originality, speed (to be delivered in short time), cost, catchiness (on an interesting topic), and timeliness (to be delivered in due time). These seven features were to be marked in the order of importance from 1 to 7, from the most important to the least. As seen in Chart 10, the most important three features were accuracy, functionality and originality for most of the participants in all three groups; speed being the fourth in the list, followed by cost and then catchiness or timeliness. The first three features – accuracy, functionality, and originality – are the feature that MT systems lack the most. The overall negative attitude toward MT might be explained with the fact that it does not meet the users’ expectations so far.

Chart 10. Priorities in a translation task

4. Conclusion

The current study tried to explore the general situation in Turkey in the field of translation technologies by three different but parallel surveys administered to translation students, faculty members of T&I departments, and translation professionals. Answers from 271 participants were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. The results of the analyses provided answers to the research questions of the study.

The first research question aimed at depicting the profiles of the faculty members of the T&I departments, translation professionals, and translation students in Turkey. Answers to a series of parallel questions in three different surveys provided an answer for this question. Translation students and professionals use technology extensively in their daily lives and they have integrated technology in their academic or professional work to a considerable extent. However, there is still a portion of students who never took a course on translation technologies or even computer technologies. This percentage is higher for translation professionals, and yet translation professionals are reported to be more competent in using computers and technologies than both students and faculty members. This is likely to indicate that most graduates learn about technologies through their personal efforts instead of within their studies. The faculty members have their graduate degrees from various related fields, only about one fourth in T&I. This shows the need for more scholars specializing in this field, especially in translation technologies. Similarly, the fact that some of the practicing translators have their academic degrees in non-related fields brings the institutionalization of the translation profession in Turkey into question. Although there are certain attempts to restrict graduates of unrelated fields from working in translation positions2, there is still a lot to be done.

Secondly, the study attempted to gather views of the faculty members of the T&I departments, translation professionals, and translation students about the present and future status of translation technologies in the academia and in the market. The results show that MT use and PE practice is not common in Turkey. The main reason is the lack of quality and accuracy of the MT output for Turkish language. There seems to be lack of interest also, especially from the part of the faculty members, although they were more optimistic about the progress of MT systems in the future. Translation students, on the other hand, seemed to be more concerned about the future of translation profession because of the developments in MT. In this vein, willingness to contribute to the betterment of MT systems through post-editing was low among translation professionals, but most faculty members believed that this should be a common practice. Here, there seems to be a major difference between how translation student and professionals, and faculty members perceive machine translation. The first two groups might be looking at MT primarily as the cause of less translation jobs, whereas the latter as an inevitable scientific progress. Post-editing skills do not seem to be an essential asset for a graduate in Turkey yet since MT use in the market is limited and MT output often lack accuracy for Turkish. Nevertheless, special training is seen as a requirement for post-editing jobs by some faculty members and professionals. The disapproval by most of the participants of the idea that long and boring texts should be translated by machines so that translators can focus on more interesting and creative tasks can be interpreted as the reluctance to building efficient MT systems in Turkey, if not as the reflection of the fear of losing jobs. Nevertheless, faculty members and professionals are proponents of more interdisciplinary research on MT, again with more faculty members willing to be part of it than translation professionals. This finding shows that major actors in the translation field have mixed and sometimes confused feelings and views about MT. This might be resulting from the fact that there have not been any research studies providing empirical evidence in regard to the contribution of MT to the translation process yet.

Finally, the implications for possible steps to be taken both by the academia and the market in order to promote translation technologies for Turkish language should be discussed within the framework of the results of the current study. The starting point seems to be the lack of translation and interpreting scholars specializing in technology and low number of studies on this topic. More graduate students can be guided to work in this area in order to increase the number of instructors to teach technology courses and to conduct related research. The second important step seems to be the coordinated action of T&I departments and translation companies, which would lead to curricular revisions particularly for technology courses and to a certain degree of standardization among universities. Interdisciplinary research studies involving translation and interpreting scholars, computational linguists, terminologists, and language engineers would produce promising and more trustworthy MT systems and other local CAT tools for Turkish language.

The findings of the current study have also implications for other less-commonly taught and translated languages since similar perceptions of or practices for translation technologies may exist both in academia and translation market. The relatively slower progress of MT systems, research on MT and of translation technologies may be due to lack of resources and support or lack of interest and/or need. This possible causality seems to be worth comparing with other less-commonly taught and translated languages. Along with this consideration, in further research studies, alternative ways to collect data should be developed and clients should be added to the target audience as the fourth major actor in the translation business.

References

n.d. App Tek. Accessed February 8, 2016. http://www.apptek.com/products/omnifluent-translate/index.html.

Balkul, Halil İbrahim. 2015. “Türkiye’de Akademik Çeviri Eğitiminde Çeviri Teknolojilerinin Yerinin Sorgulanması: Müfredat Analizi Ve Öğretim Elemanlarının Konuya İlişkin Görüşleri Üzerinden Bir İnceleme.” Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Sakarya University.

Bowker, Lynne. 2002. Computer-Aided Translation Technology: A Practical Introduction. Ottawa: Ottawa University Press.

Büyükaslan, Ali. n.d. Bilgisayar Destekli Çeviri Üzerine Bir İnceleme. Accessed February 8, 2016. http://turcologie.u-strasbg.fr/dets/images/travaux/ali%20buyukaslan%20bilgisayar%20destekli%20ceviri.pdf.

Canım, Sinem. 2011. “Translation Memory Systems for Avoiding Context Deficiency.” Istanbul University Journal of Translation Studies 1-18.

Canım-Alkan, Sinem. 2013. “Lisans Düzeyinde Çeviri Eğitiminde Teknoloji Eğitiminin Yeri / The Place of Technology Education Within Undergraduate Degree Programs on Translation.” İ.Ü. Çeviribilim Dergisi / Istanbul University Journal of Translation Studies 1 (7): 127-147.

Chan, Sin-wai, ed. 2015. The Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Technology. London: Routledge.

Ersoy, Hüseyin, and Halil İbrahim Balkul. 2012. “Teknolojik Gelişmelerin Çevirmen ve Çeviri Mesleği Açısından Olumlu ve Olumsuz Etkileri: Çeviri Alanında Yeni Yaklaşımlar.” Akademik İncelemeler Dergisi 7 (2): 295-307.

Eruz, Sakine. 2003. Çeviriden Çeviribilime. İstanbul: Multilingual.

Gümüş, Volga Yılmaz. 2014. “Teaching Technology in Translator-Training Programs in Turkey.” Edited by E. Torres-Simon and D. Orrego-Carmona. Translation Research Projects 5. Tarragona: Intercultural Studies Group. 25-35.

-. 2013. “Training for the Translation Market in Turkey: An Analysis of Curricula and Stakeholders.” Doctoral Thesis. Tarragona: Universitat Rovira i Virgili. http://www.tdx.cat/bitstream/handle/10803/127111/Volga_YILMAZ_GUMUS_ThesisTDX.pdf?sequence=1.

Hakkani, Dilek Zeynep, Gökhan Tür, Kemal Oflazer, Teruko Mitamura, and Eric H. Nyberk. 1998. “An English-to-Turkish Interlingual MT System.” In Machine Translation and the Information Soup, edited by David Farwell, Laurie Gerber and Eduard Hovy, 83-94. New York: Springer.

Hutchins, John. 2009. Compendium of Translation Software. Directory of commercial machine machine translation systems and computer-aided translation support tools. January. http://www.hutchinsweb.me.uk/Compendium-15.pdf.

Macdonald, R. Ross. 1963. “The history of the project.” In Georgetown University Machine Translation Project: General report 1952-1963, edited by R. Ross Macdonald, 3-17. Washington D.C.

Oflazer, Kemal, and Ilknur Durgar-El Kahlout. 2008. “Statistical Machine Translation between English and Turkish (Grant No: 105E020).” Final Report, The Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (Türkiye Bilimsel ve Teknolojik Araştırma Kurumu, TÜBİTAK).

Öner, Işın Bengi. 2006. “Yerelleştirme”nin Tanımı. June 1. Accessed June 25, 2015. http://ceviribilim.com/?p=234.

Prensky, Marc. 2001. “Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants.” On the Horizon (MCB University Press) 9 (5): 1-6. Accessed June 25, 2015. http://www.marcprensky.com/writing/prensky%20-%20digital%20natives,%20digital%20immigrants%20-%20part1.pdf.

Sahin, Mehmet, and Nilgün Dungan. 2014. “Translation testing and evaluation: A study on methods and needs.” The International Journal of Translation and Interpreting Studies 6 (2): 67-90.

Sezer, Ayhan. 1991. “Bilgisayarlı Çeviri Mümkün müdür?” Hacettepe Üniversitesi Çeviribilim ve Uygulamaları Dergisi 1 (1): 49-62.

Sezer, Ayhan. 1991. “Bilgisayarlı Çeviri Mümkün müdür?” Hacettepe Üniversitesi Çeviribilim ve Uygulamaları Dergisi 1 (1): 49-62.

Şahin, Mehmet. 2013b. Çeviri ve Teknoloji (Translation and Technology). İzmir: İzmir Ekonomi Üniversitesi Yayınları (Izmir University of Economics Publications).

Şahin, Mehmet. 2015. “Çevirmen Adaylarının Gözünden İngilizce-Türkçe Bilgisayar Çevirisi ve Bilgisayar Destekli Çeviri: Google Deneyi (Machine Translation and Computer-Aided Translation for English-Turkish from the Viewpoint of Prospective Translators: The Google Experiment).” Hacettepe Üniversitesi Çeviribilim ve Uygulamaları Dergisi (Hacettepe University Journal of Translation Studies) (21): 43-60.

Şahin, Mehmet. 2013c. “Technology in Translator Training: The Case of Turkey.” Hacettepe University Journal of Faculty of Letters 30 (2): 173-190.

Şahin, Mehmet. 2009. “Teknoloji ve Çevirmen Eğitimi (Technology and Translator Education).” In Çeviribilim, Dilbilim ve Dil Eğitimi Araştırmaları (Research on Translation Studies, Linguistics and Language Teaching), edited by Neslihan Kansu Yetkiner and Derya Duman, 334-344. İzmir: İzmir Ekonomi Üniversitesi Yayınları (Izmir University of Economics Publications).

—. 2013d. “Using MT post-editing for translator training.” Tralogy II. Paris: Institut de l’information scientifique et technique. Accessed June 25, 2015. http://lodel.irevues.inist.fr/tralogy/index.php?id=255.

Şahin, Mehmet. 2013a. “Virtual Worlds in Interpreter Training.” The Interpreter and Translator Trainer 7 (1): 91-106.

Troike, R. C. 2011. “Transfer grammar: from machine translation to pedagogical tool.” In Trends in Linguistics, Studies and Monographs [TiLSM]: Languages in Contact and Contrast: Essays in Contact Linguistics, by V. Gast, 469-476. Meuchen, DEU: Walter de Gruyter.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank all the participants for their valuable contribution to this study. I would also like to thank Simon Edward Mumford for proof-reading the final draft.

1 In the current study, the term “translation technologies” refer to all software and hardware used in the translation and interpreting process, including machine translation.

2 See the 69-page long proposal (in Turkish) prepared by the Prime Minister’s Office: http://www.igb.gov.tr/Kutuphane/Ara%C5%9Ft%C4%B1rma%20Raporu%20-%20T%C3%BCrkiyede%20%C3%87evirmenlik%20Mesle%C4%9Fi.pdf (Last accessed: June 25, 2015)