Ina Sîtnic

Department of Translation, Interpretation and Applied Linguistics

Faculty of Foreign Languages and Literatures

Moldova State University

inasitnic@gmail.com

Abstract

This study is a didactic approach to consecutive interpreting (CI) from English into Romanian aimed at assessing undergraduates’ CI skills. It intends to determine the role of sight translation (ST) as a pre-interpreting exercise in testing would-be interpreters’ skills. The results presented in the paper derive from a qualitative and quantitative research conducted at the Department of Translation, Interpretation and Applied Linguistics, Moldova State University. The experimental study is based on the analysis of errors of interpretation according to the classifications of H. Barik (1997), B. J. Delisle (2003), R. D. Gonzales et.al. (2012) and G. Lungu-Badea (2012) as well as on the types of errors identified in students’ translation versions.

Keywords: consecutive interpreting, sight translation, consecutive interpreting skills, errors of interpreting, didactic approach.

Introduction to consecutive interpreting

Consecutive interpretation (CI) is one of the two main modes of conference interpreting, the second mode being simultaneous interpreting. Referring to consecutive A. Gillies states that it “[…] is considered by many to be superior of the two” (Gillies 2005, 3). CI implies a combination of what D. Gile called “efforts”, i.e. mental activities like listening and analysis, note-taking, short-term memory, coordination, remembering, note-reading and production (Gile, 1995). Put in a concise definition, to interpret consecutively means to listen to the information verbalized by the speaker, and to subsequently reproduce it into another language. Although it sounds fairly easy to accomplish, the process of acquiring good CI skills requires constant cognitive effort materialised into abilities to use it in order to perform to the highest standards. Citing R. Setton and A. Dawrant, two well known conference interpreters and authors of “Conference Interpreting A complete Course” and “Conference Interpreting A Trainer’s Guide”, “A good consecutive is very satisfying, but requires several months of training to reach basic competence, a year or two to attain a solid professional level (even for the best students) and, like anything that is variable and complex, years to master.” (Setton, Dawrant 2016, 144).

The role of sight translation as a preliminary exercise in acquiring consecutive interpreting skills

Although CI shares the same communicative role with sight translation (ST), it is important to pinpoint that there are differences between the two modes in terms of mental processes and mechanisms activated in the delivery of the message in the target language. Citing I. Cenkova regarding her view on ST, the author says that it “[…] is one of the basic modes of interpreting, alongside consecutive interpreting with/without notation and simultaneous interpreting in a booth with/without text. It is a dichotomous process of language transfer from the source language (SL) into the target language (TL) as well as from a written into an oral form.” (Cenkova 2010, 320).

Despite obvious similarities between the types of translation in question that reside in the oral production of a message, the need for effort coordination and split attention in the translation process, recent research by M. Agrifoglio has indicated that ST should be distinguished from CI as they are performed under different conditions; in one case the source-text is written and permanent, while in the other it disappears once it is expressed, which contributes to significant differences between ST and CI with regard to information reception, processing, and production (Agrifoglio 2004).

Referring to the role of ST in the academic environment J.V. Dyk (2009) notes that it is “a highly beneficial method to improve translation and communication skills among language learners […], to teach students to avoid literal and non-idiomatic translation […] and to teach students learn to re-express the meaning of the source-text in their own words and to compensate for the insufficient language knowledge and intuition by relying on the context already known to them” (Dyk 2009, 203). “Practicing sight translation prepares students in their training as translators,” states J.V. Dyk (Dyk 2009, 205).

The error analysis on the basis of D. Gile’s Effort Models (D. Gile 1995, 2009) showed that ST brings more errors of expression, while CI and simultaneous interpreting lead to more errors of meaning. In ST the interpreter indulges with the speed of delivering the message in the TL and does not have to follow the speaker as in consecutive or simultaneous mode.

Sight translation presupposes higher cognitive demands (Cenkova 2010, 321) as the interpreter is in direct contact with the source-text which, increases the risk of lexical interference and imitation of the original, especially in terms of lexical and syntactical structure. Therefore, ST should make students aware of the danger of language interference and the need of careful switching between two different linguistic codes in order to provide appropriate translation versions. Other benefits of ST in interpreter education reside in better text orientation, non-linear approach to text and identification of core information (Cenkova 2010, 322). B. Moser-Mercer also strongly supports the pedagogical value of ST in conference interpreting training, arguing that it helps students detach themselves from the original text, increase their speed of analysis, and manipulate a text with syntax and stylistics (Moser-Mercer 1994).

Aim of the paper

This research is an attempt at determining the role of ST in would-be interpreters’ acquisition of CI competences. In this respect, the paper presents the results of an experimental study in which ST was used as a pre-CI exercise to test undergraduates’ competences. The results obtained showed that the process of ST improved the quality of the product of CI regarding lexical, grammatical and semantic aspects.

Methodology of the study

Two groups of 20 randomly selected 2nd year undergraduates from the Department of Translation, Interpretation and Applied Linguistics took part in the study. Ten students constituted the experimental group (EG) and 10 students – the control group (CG). The participants were students with English as first foreign language and Romanian as mother tongue, attending their first practical course of consecutive interpreting at the Department of Translation, Interpretation and Applied Linguistics. The EG was subject to a preliminary exercise which consisted in the ST of the 3 min. transcribed speech „Soap operas – not just a form of entertainment”. After applying the preliminary exercise to the EG, students in both groups interpreted the speech consecutively. The discourse was selected from the Speech Repository of the DG SCIC. It is intended for didactic purposes, level beginners. Since the participants were just introduced to practical aspects of CI, very short Consecutive interpreting mode without note taking was applied (Setton, Dawrant 2016, 135). The speech was segmented into 19 meaningful units S1 to S19 (see Appendix), with a duration of 5-10 seconds each. The reason behind using very short consecutive is that at this stage of CI competence acquisition students are introduced to note-taking techniques only by the end of the semester, while our purpose was to obtain an as detailed interpretation as possible. It is worth noting that EG students did not rehearse the ST of the transcribed discourse, i.e. they produced a first ST version. Students from both groups involved in the study were announced the key-words and a short description of the speech before proceeding to its CI. Also, in order to preserve students’ anonymity an identification code was attributed to substitute for their names. Therefore, students in the CG were attributed codes from A1 to A10, and students in the EG were attributed codes from B1 to B10.

The translation of the discourse took place in the language laboratory of the Department of Translation, Interpretation and Applied Linguistics. For the subsequent processing of the quality of the translated discourse, students recorded the ST and CI versions with the help of the audio software Audacity. Thereafter, for the purpose of qualitative and quantitative discourse analysis all the CI versions provided by the students were transcribed. Our attempt to use speech to text recognition software failed due to background noises that interfered with students’ speech and their low voice that could not be “heard” by the program.

A short description of error categories in interpreting

The CI competences were assessed in number of errors attributed to the following categories: (1) language mistakes, (2) lexical errors, (3) grammatical errors, (4) ambiguities, (5) mistranslation, (6) incorrect meaning, (7) nonsense, (8) pragmatic errors, (9) additions, (10) omissions, (11) inappropriate comments, (12) approximations. This classification is rooted in the error categories outlined by H. Barik (1997), B. J. Delisle (2003), R. D. Gonzales et.al. (2012) and G. Lungu-Badea (2012) and also takes into account the types of errors identified in students’ translation versions.

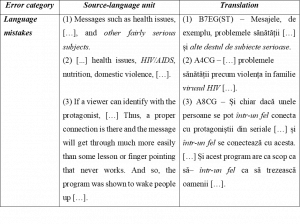

(1) Language mistakes are determined by insufficient knowledge of grammar and lexis of the TL. They do not distort the meaning of the speech, but may cause some alteration at local level. Among the most encountered types of language errors should be noted barbarisms, solecisms, inappropriate expressions and language interferences.

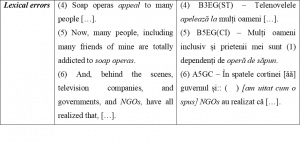

(2) Lexical errors lead to inappropriate translation, with a probability of distorting the meaning of the speech. They are triggered by weak or inadequate access to synonyms, poor linguistic abilities, literal translation and time constraint.

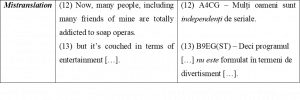

(3) Grammatical errors are associated with poor rendering of grammatical categories of tense, number, mood or errors of syntax that result in distortion of meaning. Reasons for committing such errors are poor grammatical knowledge and lack of attention.

(4) Ambiguity is an impediment towards understanding the target-discourse. It is lexical, syntactical and semantic-pragmatic in nature, usually associated with homonymy, polysemy, elements of coordination, phrases, ellipsis, pronouns, etc.

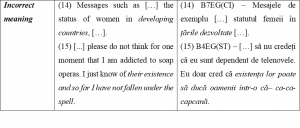

(5) Mistranslation resides in attributing to a word or syntagm a wrong meaning which is opposite to the one intended by the speaker (Delisle 2003, 33). Causes of mistranslation are related to lack or poor understanding of the source-discourse (SD) and problems with listening to it.

(6) Incorrect meaning is the result of an erroneous appreciation of the meaning of a word or utterance in a given context but does not lead to opposite meaning (Delisle 2003, 42). Reasons causing incorrect meaning are the same as with mistranslation.

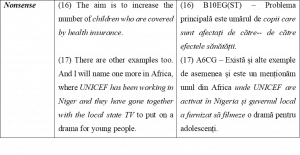

(7) Nonsense resides in attributing an erroneous meaning to the source utterance resulting in absurd expression in the TL (Delisle 2003, 50). Nervousness and problems with understanding the original are among causes of nonsense.

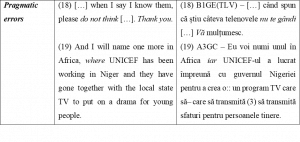

(8) Pragmatic errors are mostly associated with mixing language registers, omitting cohesive elements at intra- and/or inter-utterance level, using inappropriate pragmatic connectors that result in incoherence.

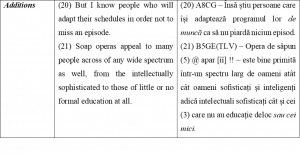

(9) Addition consists in the unjustified creation and introduction in the target discourse (TD) of information that does not exist in the SD. Additions are motivated by poor attention and concentration as well as misunderstanding the SD and the desire of not keeping silent while interpreting when some segments are misunderstood.

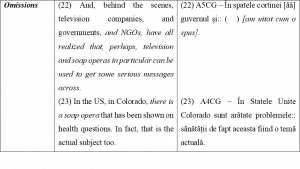

(10) Omission means to unjustifiably not render in the target discourse information that appears in the SD which results in loss of meaning. They occur at word level, phrase level or even entire utterances may be omitted due to the students’ inability to reformulate the meaning into the TL because of time constraints, lack of understanding of the SD, rendering numbers and enumerations without focus to their co-text, slow information processing capacity, lack of attention and concentration.

(11) Inappropriate comments occur as language units in the result of the cognitive processes that one verbalises in interpreting. Such interventions interfere with the TD and distract the listener. Inappropriate comments are triggered by memory failures, poor linguistic knowledge or they may act like stimulus for the activation of information retrieval.

(12) Approximation or imprecision are used to avoid exactness in determining the real value of the information, or the truth value of an assertion, etc. in the process of interpretation. Causes of this type of error are short-term memory retrieval failure and insufficiency or lack of linguistic knowledge.

Data analysis and results

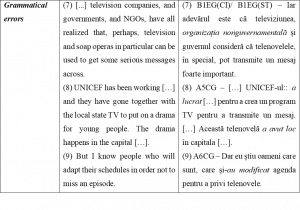

A total number of 132 errors were found in the EG(ST), 120 CI errors were counted in EG(CI) and 244 errors were identified in the CG. Figure 1 below presents the frequency distribution of errors per each category of interpretation error in the studied groups.

Figure 1. Percentage distribution of errors in EG and CG

The total duration of the ST versions (56:47 min.) provided by students in the study exceeded the total duration of the CI versions – 33:58 min. in CG and 36:59 min. in EG(CI).

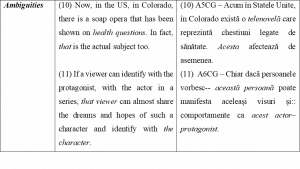

The comparative analysis of errors shows that the number of language mistakes prevailed over the rest of error categories in CG (31.97%) as well as in EG in both modes of translation (36.36% in EG(ST) and 45.83% in EG(CI), while the lowest number of errors was attributed to mistranslations (0.41% in CG, 0,76% in EG(ST) and 0% in EG(CI), inappropriate comments with the same indices as for mistranslations and approximations with no errors in CG and EG(ST) and 0,83% in EG(CI) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Numerical distribution of errors in EG and CG

The lexical errors produced by the students in the experimental group in ST slightly outnumbered (by 1%) the share of errors identified in the same group in CI and the share of morpho-syntactical errors was 6% higher in the experimental group in the process of ST compared with the rate of the same types of errors in this group in CI.

As follows, we provide examples that pertain to each category of errors of translation and interpretation. The fragments were extracted from both groups under study and are followed by an analysis that includes explanations from a linguistic and a translation perspective.

The structure marked in italics in example (1) requires the rearrangement of the words so that it makes a correct and logical expression. The appropriate word order in Romanian would be adjective (alte) + noun (subiecte) + adverb and preposition (destule de) + adjective (serioase).

Fragment (2) contains a language mistake associated with linguistic redundancy and is manifested by using the word “virus” before the acronym “HIV”. The disambiguation of “HIV” (“human immunodeficiency virus”) already has the word “virus” in its structure and therefore, its repetition in „virusul HIV” (en. “HIV virus”) is pleonastic. A correct expression must be „infecția cu HIV”.

In example (3) we emphasize the unwanted effects of fillers or “parasite words”. The repeated use of „într-un fel” (en. “somehow”) is triggered by the difficulty to explain an idea that the student cannot express in enough words. The frequent repetition of such linguistic structures is associated with the limited vocabulary of the speaker, the slow speed of transforming thoughts into words, difficulties of understanding the meaning expressed in the SD.

Fragment (4) contains an example of false analogy – a word or a word combination identical in form in English and Romanian but which has total or partial meaning in these languages. One of these words is “to appeal to” that was incorrectly translated into Romanian as “a apela la”. A correct translation version is “a fi pe placul cuiva”.

The calqued translation of the syntagm “soap opera” as “operă de săpun” is as hilarious as it is erroneous. The correct version in Romanian is “telenovelă” or “serial”.

Referring to lexical errors, we should mention the incorrect translation of abbreviations. An eloquent example in this respect is the use of the abbreviated form of “nongovernmental organisation” (“NGO”) as it appears in English, while there already exists a Romanian correspondent which should have been used, namely “ONG”.

Since the original makes reference to the plural of the noun “nongovernmental organisation” in example (7) the student-interpreter should have preserved the same grammatical category of number. The use of the singular of the noun resulted in meaning distortion.

In utterance (8) present perfect continuous and simple present were rendered via past tense in Romanian, while in (9) simple future was transposed via past tense.

The confusion in example (10) presented above is grammatical in nature and resides in the use of the demonstrative pronoun „aceasta” without any concrete and clear reference to the noun that it determines „telenovela” or „chestiunile legate de sănătate”.

The demonstrative adjective „aceasta” in the syntagms emphasized in italics in example (11) creates meaning ambiguities because the original does not make reference to any person, be it actor or protagonist.

The verb in utterance (13) should have been conjugated in its affirmative form in order to be true to the original.

The semantic error in example (14) lies in the wrong translation of the word combination “developing countries”, its appropriate equivalent being “țări în curs de dezvoltare”.

In example (15) the error consists in incorrect translation into Romanian of the expression „to fall under the spell” and the introduction of the modal verb „a putea” (en. “can”) which is missing in the original.

Utterances (16) and (17) are characterised by partial lack of meaning caused by inappropriate lexical choice and syntax.

In fragment (18) there is an inconsistency with the language register which is expressed by means of switching from the second person singular „tu” to the second person plural „vă” to show politeness.

In fragment (18) there is an inconsistency with the language register which is expressed by means of switching from the second person singular „tu” to the second person plural „vă” to show politeness.

In example (19) it can be noticed the incorrect use of the syntactic-pragmatic link word. In order to preserve the semantic relations as in segment S16 from the SD, the student should have used the conjunction „unde” (en. “where”) that introduces a place clause instead of using the coordinating conjunction “iar” (en. “but”).

The additions in (20) and (21) are illustrated by words and word combinations that occurred in the translation versions but are missing in the original. Such additions distort the meaning of the utterance.

Example (23) contains an omission of the channel by means of which the health problems are presented.

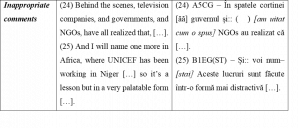

Inappropriate comments (24) Behind the scenes, television companies, and governments, and NGOs, have all realized that, […].

Inappropriate comments are shown in examples (24) and (25) in square brackets. Such words and phrases interrupt the fluency and the train of thought of the discourse and are proof of lack of professionalism.

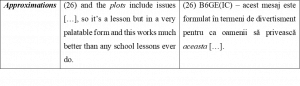

The approximation in example (26) is rendered by the demonstrative pronoun “aceasta” (en. “this”) that substitutes a concrete noun that should clarify the meaning.

The qualitative and quantitative analysis of students’ translation versions showed that students make mistakes and errors in different ways, with language mistakes and semantic errors being the most encountered in both groups and both modes of translation.

Conclusions

Some of the advantages of ST in the process of CI competence acquisition, as stated earlier in the body of this paper, reside in helping students understand the meaning of the source-text, reformulate the message while avoiding lexical transfer and translating without source-text lexical and syntactical interference. From these perspectives, as the results of this experimental study showed, visual interference in ST was more noticeable than audio interference in CI in what lexical aspects are concerned. Nevertheless, applying the ST exercise prior to CI had beneficial effects for students in the EG for the subsequent process and product of CI. The number of lexical, grammatical and semantic errors was substantially lower in the EG(CI) compared with EG(ST) and CG. Also, the numeric distribution of errors in EG(CI) and CG showed a much lower number of errors for all categories.

A suggestion to be made in light of this study would be the conduct of replications of the experiment so that more accurate data and reinforcement of the arguments are obtained.

References

1. Čeňková, Ivana. 2010. Sight translation: Prima vista. In: Gambier, Yves; Doorslaer, Luc van (ed.), Handbook of Translation Studies. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 320-323.

2. Delisle, Jean. 2003. La traduction raisonnée: manuel d’initiation à la traduction professionnelle, anglais, français: méthode par objectifs d’apprentissage. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press.

3. Dyk, Jeanne Van. 2009. Language Learning through Sight Translation. In: Witte, Arnd; Harden, Theo et al. (ed.), Translation in Second Language Learning and Teaching. Bern: Peter Lang. p.203-214.

4. Gile, Daniel. 1995. Basic Concepts and Model for Interpreter and Translator Training. Amsterdam/ Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

5. Obidina, Veronika. 2015. Sight Translation: Typological Insights into the Mode. In: Journal of Siberian Federal University. Volume 8 (1): 91-98.

6. Setton, Robert, Dawrant, Andrew. 2016. Conference Interpreting: a Complete Course. Amsterdam: Benjamins Translation Library.

7. Viaggio, Sergio. 1995. The Praise of Sight Translation (And Squeezing the Last Drop Thereout of). In: The Interpreters’ Newsletter. (6): 33-42.

8. Viezzi, Maurizio. Information Retention as a Parameter for the Comparison of Sight Translation and Simultaneous Interpretation: An Experimental Study. In: The Interpreters’ Newsletter. (2): 65-69. 1989.

Appendix. Source discourse transcription and segmentation

Soap operas – not just a form of entertainment

S1. Now, many people, including many friends of mine are totally addicted to soap operas.

S2. I’m thinking immediately of some of the British series that I know, perhaps, best. Things like Coronation Street and EastEnders.

S3. And now, when I say I know them, please do not think for one moment that I am addicted to soap operas.

S4. I just know of their existence and so far I have not fallen under the spell.

S5. But I know people who will adapt their schedules in order not to miss an episode.

S6. Soap operas appeal to many people across of any wide spectrum as well, from the intellectually sophisticated to those of little or no formal education at all.

S7. And, behind the scenes, television companies, and governments, and NGOs, have all realized that, perhaps, television and soap operas in particular can be used to get some serious messages across.

S8. That might be the best way. Messages such as health issues, HIV/AIDS, nutrition, domestic violence, the status of women in developing countries, and other fairly serious subjects.

S9. If a viewer can identify with the protagonist, with the actor in a series, that viewer can almost share the dreams and hopes of such a character and identify with the character.

S10. Thus, a proper connection is there and the message will get through much more easily than some lesson or finger pointing that never works.

S11. Now, in the US, in Colorado, there is a soap opera that has been shown on health questions. In fact, that is the actual subject too.

S12. The aim is to increase the number of children who are covered by health insurance.

S13. This is a problem because many children are eligible but they don’t have any coverage for one reason or another.

S14. 6, S15. but it’s couched in terms of entertainment so that people will watch, be interested and nevertheless, pick up a very important message indeed.

S16. There are other examples too. And I will name one more in Africa, where UNICEF has been working in Niger

S17. and they have gone together with the local state TV to put on a drama for young people.

S18. The drama happens in the capital, Niamey, and the plots include issues concerning the danger of HIV/ AIDS, prevention methods,

S19. so it’s a lesson but in a very palatable form and this works much better than any school lessons ever do. Thank you.